Deaf Jam

West Hartford (Google Maps Location)

May 28, 2009

2019 Update: I see that this place is now called The Alice Cogswell Heritage House.

Certain museums give me that little burst that keeps me excited to continue this website. They are usually ones like this one: Small(ish), singularly devoted, unique… And cared for by really, really great people. I hit one of these types of places every 20 or so museums. Don’t get me wrong, I love the big brassy places too, but there’s just something very attractive about these dedicated little places that few people know about.

I had read about this museum in a local West Hartford magazine (we have about 7 somehow) called Seasons. It was another one of those “Oh wow” moments for me in that I did not know about the museum – and yet it’s only a couple miles from my house.

It’s an “appointment only” place, so I didn’t think too much about it until I was contacted by freelance writer Dan and was told about his wishes to shop and write an article about me and this very website. After a couple phone interviews, Dan wondered if we could spend a full CTMQ day together, doing what I do. I took him up on the offer and began preparing the most efficient, yet interesting day I could come up with.

Dan the Man

And since our day would begin with dropping Damian off at school and then shuttling him to daycare later, we had to spend the morning around West Hartford. Voila – Our first stop would be the ASD Museum. I contacted Gary Wait, the curator, tour guide and general all around great guy and made a date.

As usual with these types of places, I had no idea what to expect. We had to go through security at the school, park and knock on the heavy door to where the museum is. Once Mr. Wait answered the door, I was “in my comfort zone,” so to speak.

An older gentleman, with impeccable manners, sweater vest and tie, Mr. Wait was happy to receive us. The whole place feels like a cozy and homey grandfather’s house, complete with a soft tan carpet and yes, an actual grandfather human. We removed our shoes (although we were told we didn’t have to, because “the housekeepers will take care of it”) and began our tour.

Mr. Wait was certainly curious why two non-deaf younger guys with cameras and notepads were at his museum. To his credit, he accepted our (truthful) explanations and was happy to help us out on our related, but different, endeavors. I had no idea all that I’d learn here and how many interrelated CTMQ stops I’d begin weaving together with some of ASD’s history. I love when that happens.

The ASD is the oldest permanent school for the deaf in the United States. Not only that, but the school became the first recipient of state aid to education in America when the Connecticut General Assembly awarded its first annual grant to the school in 1819. When the United States Congress awarded the school a land grant in the Alabama Territory in 1820, it was the first instance of federal aid to elementary and secondary special education in the United States. Amazing. Want more? Mr. Wait (and maybe others) has put together a Deaf History Trail around Hartford. And there is a cool statue of a major player in the school’s story in a prominent (and notoriously dangerous) intersection in Hartford. So much to discuss…

Fortunately, the ASD website is better about providing pertinent information than many other, more well known museums around the state. So with a tip o’ the hat to them, I’ll use their words instead of mine. And I’m sure that Dan will have some stuff in his article (Connecticut Magazine bought his idea and will run the story about me an early 2010 issue…)

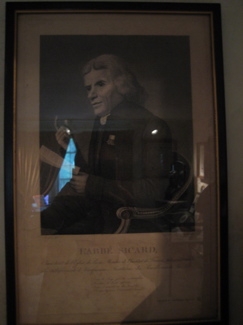

Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet was born in Philadelphia on December 10, 1787, to French Huguenot parents. His family later moved to Hartford, near the home of Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell, a prominent surgeon in the town. Dr. Cogswell’s daughter Alice had been deafened in infancy by a childhood illness associated with a prolonged high fever. Young Gallaudet, a divinity student and a graduate of Yale College, was home from Andover Seminary convalescing from a chronic illness. He observed Alice’s attempts to communicate with her siblings and the neighborhood children at play.

Although not trained to teach deaf children, Gallaudet convincingly demonstrated that Alice could learn and should be afforded the opportunity to attend school. Dr. Cogswell was excited about the prospects for educating his daughter and all deaf children in the country. The Congregational Churches of New England, probably the most reliable source of census data of that day, reported 80 deaf children in New England and approximately 800 deaf children in entire U.S. Gallaudet, Cogswell, and ten prominent citizens decided an American school for the deaf was sorely needed. In just one afternoon, sufficient funds were raised to send Gallaudet to Europe to study the methods of teaching the deaf.

The Braidwood family, formerly of Edinburgh, Scotland, operated a school for the deaf in London as a family business. They did not wish to share their knowledge to train prospective teachers of the deaf, unless terms could be negotiated to pay the Braidwood family, on a per capita basis, for each deaf child who would be subsequently educated using the Braidwood methods. Gallaudet would not sign such an agreement or embrace the doctrinal tenets of the Braidwood system. He remained in London for 13 months, but gave up hope of bringing the Braidwood system back to Hartford.

The Abbe Sicard, Director of the French Institute for the Deaf in Paris, was in London at that time with his two deaf assistants, Jean Massieu and Laurent Clerc, giving lectures and demonstrations on the methods used to educate deaf children in France. Gallaudet was familiar with the work of the French School, and had even met with the abbe at the beginning of his visit to England, but it was not until he had despaired of reaching his goal with the English that he turned to the French. Gallaudet attended one of the lectures, met with the abbe and his assistants, and accepted their invitation to enter the teacher preparation program at the French school.

Laurent Clerc worked closely with Gallaudet, but there was not sufficient time for Gallaudet to master all of the techniques and manual communication skills before his diminishing funds forced him to book return passage to America. Gallaudet prevailed on Sicard to allow Laurent Clerc to accompany him on the return trip to America to establish an American School. In the fifty-five days of the return voyage, Gallaudet learned the language of signs from Clerc, and Clerc learned English from Gallaudet.

The oldest existing school for the deaf in America opened in Bennett’s City Hotel on April 15, 1817. The school became the first recipient of state aid to education in America when the Connecticut General Assembly awarded its first annual grant to the school in 1819. When the United States Congress awarded the school a land grant in the Alabama Territory in 1820, it was the first instance of federal aid to elementary and secondary special education in the United States. More than four thousand alumni have claimed this historic school as their alma mater.

The founding of the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Conn., in 1817 was a crucial milestone in the way society related to people with disabilities. The time and place are significant because it was a unique conjunction of different currents which led to the school’s establishment.

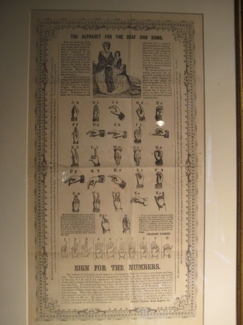

Many threads in developing U.S. society coalesced in Hartford in the early nineteenth century. The importance attached to universal literacy (by no means common in the world at the time) and the particular missionary religious doctrines of the prevalent Protestant sects provided both means and motive for the attempt to educate deaf people. The concept of self-reliance and the belief that religious salvation is possible through understanding the Bible determined the methods and purposes of the founders. Literacy, salvation and the skills needed to earn a living were the goals. Achieving these required clarity and fluidity of communication, which is why the school was based on sign language from the start.

The experiment aroused great interest. Governor Oliver Wolcott, in an 1818 proclamation, asked the public, “to aid . . . in elevating the condition of a class of mankind, who have been heretofore considered as incapable of mental improvement, but who are now found to be susceptible of instruction in the various arts and sciences, and of extensive attainments in moral and religious truth.” His words express the great change in attitude toward deaf people which had only just occurred.

The school’s founders were well aware of the groundbreaking importance of their project, and they and their successors saved a great many letters, teaching aids, illustrations, books and other objects. These materials remained in the school’s possession and now form a rich collection. They document not only the history of deaf education, but also the study of educational techniques, the history of religion, and the history of Hartford, of Connecticut, and of the United States.

Which brings us to the museum and archives. I’ll jump forward in a tour a bit to the archives themselves. Mr. Wait has worked with an archivist and they have nearly completed the cataloging of the massive collection, most of which is stored in offices upstairs. He first told us about the old desk in the office up there; it was a seward’s cabinet back in the day and was built by some students in – get this – 1863! There is a small plaque on the desk stating just that.

Among the thousands of items in the archives are: The oldest book on signs in English, Chirologia, 1644. Numerous books from the 17th, 18th and 19th century, in several languages, on deaf education. Personal papers of those involved in opening ASD, including founders Mason Cogswell, Thomas H. Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc; the school’s earliest pupils, notably Alice Cogswell and George Loring; Alice’s early tutor Lydia Sigourney, later a famous American poet, and others. Documents relating to the first state and first federal aid to special education in the history of the United States. Complete collection of the American Annals of the Deaf, oldest professional journal in the field, begun in 1847 by ASD staff. (Yet another cool fact!) Works by 19th and 20th century deaf artists.

On and on.

The oldest known painting of a person signing

Valuable 185-year-old letters which were lying unprotected in file cabinets have now been suitably housed; books which were turning to dust are being restored; and century-old photos, fading from exposure, are now protected. The school has made a commitment to properly stabilize, preserve and catalogue the collection, make it accessible to scholars and, eventually, develop interpretive exhibits and materials for the public. The school hopes to preserve for the nation’s future this precious piece of its past. Providing the best education possible for deaf and hard of hearing students remains the principle priority of the American School for the Deaf. A limited amount of funding has been made available by the school to begin the preservation, cataloguing and display of the magnificent collection housed in the ASD Archive.

Good stuff. Now, back downstairs to the more public-friendly museum area, which is housed in what appear to be the house’s old sitting and living rooms. The building used to be a residence for school directors and as I’ve mentioned, it’s homey to say the least.

Mr. Wait is the ideal guide. He loves the school’s collection and each piece is brought to life with a colorful story – which often lead to other colorful stories. Wait gauged our interest and absolutely nailed how much we cared to know about certain items.

Of course, being the nerds that we are, Dan and I ate up everything Wait told us. There is a letter from little Alice Cogswell herself. There’s a piece of Gallaudet’s luggage as well as his spectacles. Those spectacles bring me to another cool little side story… Gallaudet’s name has its own special sign: The letter G with the sign for spectacles. Now that’s pretty cool and I guess when you’re the guy who develops American sign language (for which he toned down some of the more blunt French signs for bodily and sexual functions), you get your own sign.

There is a case devoted to deaf artists, several of which attended the ASD. You’ve never heard of any of them, but you’ve perhaps seen at least one of their works. You see, the best selling Connecticut winery wine is Sharpe Hill’s Ballet of Angels. And that little boy holding a bluebird on the label? That was painted by John Brewster, Jr., one of the first students at the ASD (who happened to be 51 years old when he enrolled!) I’m happy to report that Sharpe Hill does have a little blurb about their choice for their label.

From the Sharpe Hill website:

We now needed to design a label which would complement the spiritual and beautiful name Ballet of Angels. Catherine, who with her husband Steven own Sharpe Hill Vineyard, had always admired a charming portrait of a boy holding a bluebird. Catherine discovered that the New York Historical Association owned the painting and that it was part of their museum collection in Cooperstown, New York. Catherine asked if the museum would allow the use of the image for their Ballet of Angels label. The Vollweilers were truly amazed to learn that the American artist who painted it, John Brewster, Jr, lived on the other side of the hill from Sharpe Hill Vineyard, in the town of Hampton. The home where he was born in the eighteenth century still stands in the center of town. This wonderful and amazing story only enhances the spirituality of the Ballet of Angels.

Yes, they fail to mention his deafness, but I’m still impressed.

There is a painting of the aforementioned Laurent Clerc, which is the earliest known depiction of a deaf person signing, from circa 1815. There are a bunch of Clerc relics and as you may expect, a collection of early cumbersome “ear trumpets” used as hearing aids way back when.

There is a well-preserved wedding dress of Sophia Fowler, who was a deaf student who wooed the school’s founder and ended up marrying him. There are lots of these types of random bits of early deaf education items all over the place, if you haven’t gathered that already. One of my favorites is the Victorian drawing board used by noted landscape architect Jacob Weidenmann, designer of Bushnell Park and Cedar Hill Cemetery. Weidenmann taught drawing at ASD between 1860 and 1864 while serving as Hartford’s first park superintendant.

Oh look, it’s Gallaudet’s shaving stand and his chair! In the chair is a special First Day of Issue cancellation, commemorating the issue of a US postage stamp honoring Gallaudet. The ceremonies for that issue, by the way, were right here at ASD. Awesome.

Also awesome? Deaf Barbie. I’m not sure I need to go on any further.

![]()

Tammy J. Myers says

Tammy J. Myers says

January 24, 2011 at 5:21 pmAmazing website! I grew up the Northeast part of Connecticut and did not know about your school until I researched it years after moving to Texas. I currently work at The Texas School for the Deaf and have given many tours! I love the History and very intrigued by your website as well.

I would love a tour next time I am in New England.

Respectfully,

Tammy J. Myers

Parent Liaison Administrative Assistant

Sibshop Facilitator

Texas School for the Deaf

Educational Resource Center on Deafness

1102 S. Congress Avenue

Austin, TX 78704

Steve says

Steve says

January 24, 2011 at 5:54 pmIt’s a shame when educators don’t even feel compelled anymore to read the first 2 sentences before commenting.

I wonder if Tammy noticed that this blog post is titled “Deaf Jam” and thought that was a little weird.

Anyway, I’ve forwarded her interest on to the ASD and deleted the two phone numbers she included in her original comment. Sheesh.

Keith Mousley says

Keith Mousley says

June 25, 2012 at 9:51 amI would like to visit the museum this friday (June 29)around 1:00. Is this possible?

Thank you.

Keith Mousley

Steve says

Steve says

June 25, 2012 at 10:57 amI have no idea. Contacting the actual museum and not a blog about visiting it 3 years ago would probably make more sense.

Tucker McDonald says

Tucker McDonald says

February 11, 2020 at 10:47 pmMy name is Tucker, and I am a 13 year old. I am looking for a photo of the portrait of Alice Cogswell. I am doing a research documentary on the creation of ASL and would like her image to use. I found that this musume is the only place that this exsists. Could you please help me find it? Thank you