No Need to Get Cross With Me

Storrs/Mansfield (Google Maps Location)

July 17, 2009

Please note that this was written in 2009 and that I am pretty sure this gallery no longer exists as it did back then.

I spent four (and, ahem, a half, ahem) years and several tens of thousands of my father’s hard-earned money at the University of Connecticut, earning a degree in biology. I loved it, got a good education, made a bunch of lifelong friends (in fact, I’m going to see a bunch of them tomorrow at our annual get-together before a basketball game) and had a blast. The University has undergone an unbelievable transformation since I was there in the early 90’s.

Now it’s a premier university with modern facilities, world-renown science programs, two national men’s basketball championships (who knows how many women’s), and it’s a school I’m certainly proud to call my alma mater. There are several museums on (or very near) campus and it takes several separate day-trips to hit them all. If you’re visiting with your kids, I’d suggest going to the Ballard Puppetry Museum, the Husky Heritage Sports Museum and then checking out The Dairy Bar and the various vestiges of UConn’s Ag School past over on Horsebarn Hill.

I took Damian up there one summer day to hang out with the cows and horses for a couple hours, but followed that fun up with a stop at the far less exciting (to a 3 year old) Wilbur Cross Gallery. I wasn’t sure if it qualified as a museum and really, it doesn’t – except when coupled with the well-executed companion website. And it goes without saying, the Gallery also doesn’t qualify as something fun to do for a tired little boy. But perseverance is a quality learned, so suck it up Damian, we’re going to learn about Papa’s school.

If you ever plan on visiting the school, I’m sure it will most likely be for a basketball game, a show at the Jorgensen, or some ice cream. But if you check out the school’s website and happen upon the history section, you’ll read, “When you visit the Storrs campus, be sure to see the special exhibit examining the University’s history. It is on display in the gallery of the Wilbur Cross Building.” Shhh, don’t tell them I told you, but you really needn’t do that. All you need to do is read this page – and then the UConn site, and you can consider yourself well-versed in UConnalia.

We can start with the Alma Mater that no one knows. It’s pretty bad but cut us some slack – “Connecticut” isn’t exactly easy to work into song.

Once more, as we gather today,

To sing our Alma Mater’s praise,

And join in the fellowship strong,

Which inspires our college days.

We’re backing our teams in the strife

Cheering them to victory!

And Pledge anew to old Connecticut,

Our steadfast spirit of loyalty.(Chorus)

Connecticut, Connecticut,

Thy sons and daughters true

Unite to honor thy name,

Our fairest White and Blue.

Right now, for instance, (mid 09/10 season) we’re certainly backing a team in strife. The men’s basketball team just lost to Providence. PROVIDENCE! Oof. And speaking of sporting events, the band always plays the Fight Song. I contend no one knows these lyrics either, other than spelling out “Connecticut” which I’ve always found kind of funny. Again, though the tune is pretty catchy, this is just a lyrically bad fight song.

U – Conn Husky, symbol of might to the foe.

Fight, fight Connecticut, It’s vict’ry, Let’s go.

Connecticut U – Conn Husky,

vict’ry again for the White and Blue

So go – go – go Connecticut, Connecticut U.

C – O – N – N – E – C – T – I – C – U – T

Connecticut, Connecticut Husky, Connecticut Husky

Connecticut C – O – N – N – U! Fight!(Repeat)

I’ll get to the origination of the husky as the mascot a little bit later. First, some incredibly pared down history from the school’s website.

The University of Connecticut began with a gift. Late in 1880, brothers Charles and Augustus Storrs offered the state of Connecticut a former Civil War orphanage, 170 acres of farmland and a few barns to establish an agricultural school for boys.

The gift also included $5,000 to purchase equipment and supplies. On April 21, 1881 the Connecticut General Assembly voted to establish the Storrs Agricultural School. It opened five months later on September 28, 1881, with three faculty members and 12 students.

The School’s first six students graduated in 1883 with two-year certificates in agriculture. It would not be until 1914 that four-year degrees were conferred by what was then Connecticut Agricultural College. When Storrs Agricultural School became Storrs Agricultural College in 1893, Benjamin Franklin Koons was named the first president of the institution.

Koons, a Civil War veteran and college graduate, opened classes to women in 1891 and oversaw the College’s first decade of growth. Storrs Agricultural College became Connecticut Agricultural College in 1899. The name Connecticut State College followed in 1933 and the institution officially became the University of Connecticut in 1939.

How quaint. Even today, those who have never been to Storrs are struck by just how rural it still is. Approaching campus from the south, there is no evidence at all of what looms beyond the pastures and forests one drives through before having the whole University appear in front of them. And the entire northeast corner of campus is still where the agricultural school exists today; a little bit of Iowa in Storrs.

The original building housed all the students, faculty and classrooms. Instilling confidence in the taxpayers of Connecticut, a local newspaper stated, “Instead of filling the young men up with theoretical book learning, and a great quantity of science which may not be immediately available, at a cost beyond the means of most parents, it is proposed to have a school, at which the cost of tuition will be merely nominal ($25 a year) and the price of board very low (not over $2.50 or $3 a week for 36 weeks.) Ample chance will be given for the boys to do extra work to pay, so that industrious and earnest students can earn enough for their expenses as they go. This is a very important consideration.”

Gee, it sort of sounds like the basketball program today.

The daily routine for students was rigorous: a rising bell at 6:30 each morning, with breakfast at 7 a.m. and mandatory prayers immediately following the meal; lectures and recitations ran from 8 a.m. to noon, with dinner at 12:15 p.m. All students engaged in farm work from 2 to 5 p.m., had supper at 6 p.m., and study hours from 7 to 9 p.m.

The curriculum, too, was rigorous. The students learned how to improve soil “by tillage, draining, manuring, irrigation,” and the “culture and handling of the various field, garden and orchard crops of New England – grass, grain, roots, vegetables and fruits – from planting to market. The use, care and repair of farming tools, implements and machines. The breeding, rearing, training, feeding and use of live stock – cattle, horses, sheep, swine and poultry, including the best methods of dairy practice,” said the school prospectus.

There was also the business side to farming: “keeping accounts, inventory, capital, labor, rotation of crops, systems of farming adapted to various circumstances.”

Agricultural science “will comprise those sections of physical and natural science that have a directly useful bearing upon New England farming, viz.: agricultural chemistry; agricultural physics – the relations of air, water and soil to heat, rain, dew, frost, storm; agricultural mechanics – laws of motion and friction; principles of the construction of farm tools and machines; agricultural botany and zoology – classification of animals, special history of the agriculturally important quadrupeds, birds, fish, insects, useful and injurious; anatomy and physiology of the ox, horse, etc., common diseases of cattle etc., and their domestic treatment.

There were also classes in reading, speaking, and writing on agricultural topics, as well as arithmetic and elementary geometry “as are serviceable upon the farm; surveying, and measuration of surfaces and solids.”

And they were taught “such simple carpenter and smith work as are useful in New England rural life.”

I was going to leave out the story of how the school went from a teeny tiny ag school to the thriving University it is today, but the story is actually pretty interesting.

As I’ve said, the college was founded in 1881 as the Storrs Agricultural School. It didn’t become a University until 1939 – and it was a struggle:

A letter to the editor of the New York Herald signaled early concerns about the little college in Storrs becoming a state university. The letter, published on April 11, 1897, ended with: “The logic of the school, if encouraged, will fasten upon Connecticut a State University, for which it has no use, and which it cannot afford to maintain.”

During the next several decades, the issue rose and fell, coming to a fever-pitch in the early 1920s in what became a politically charged public debate in the state’s newspapers.

Connecticut, and other New England states, had resisted establishing public state universities, counter to the movement in the rest of the country. With so many established private colleges, went the line of reasoning, why spend public money on a competing public institution?

Newspaper editorial writers in the state in 1921, for example, questioned the value of teaching English literature, French and German to farmers.

In 1925, the General Assembly voted to limit enrollment to 500 students per year, to satisfy fears that CAC would grow into a state university of immense size. (By the 1930s, the measure was ignored, and it was repealed in 1937; enrollment that year exceeded 800 students.)

But there would indeed be a state university – and the steps leading in that direction began almost as soon as the ink was dry on the 1925 legislation.

Nathan Gatchell, editor-in-chief of The Connecticut Campus, in 1928 began a print campaign to have the word “agricultural” taken out of the college’s name, maintaining that “agriculture” no longer represented the type of institution, because the majority of students were taking non-agricultural courses.

He also held that the name was a handicap to graduates seeking jobs in other fields.

The trustees were not pleased. They demanded that the administration – led at the time by acting president Charles B. Gentry, who later became the first dean of the School of Education – discipline Gatchell and “impose censorship on the Campus.” Gentry, however, did neither.

Bertram Wright, the new Campus editor in 1929, carried on the battle, with support from some of the faculty. Shortly after Wilbur Cross was elected governor in 1930, representatives of the college approached him about a change of name.

Cross appointed a committee, headed by Ernest W. Butterfield, state education commissioner, to report back to the General Assembly.

In the interim, students continued the debate, and it spilled over to state newspapers. Editorials and letters-to-the-editor called for a change of name to “Storrs State College” or “Nathan Hale College,” not just Connecticut State.

A poll of students in 1931 showed that of 407 who voted, 393 preferred “University of Connecticut,” and only 14 favored “Connecticut State College.”

The committee appointed by Gov. Cross reported early in 1933 that the word “agricultural” was indeed no longer representative of what the college offered in its curriculum and recommended that the name be changed to “Connecticut State College.”

During a legislative hearing, the descendants of founders Charles and Augustus Storrs made a pitch for the name “Storrs State College,” and a representative of Connecticut College for Women argued that “Connecticut State College” would encroach on the private college’s name.

It was pointed out, however, that the Storrs family’s contributions at that time amounted to less than the private contributions from others, not to mention the state’s investment over the years, which was then said to total $3,125,000.

Legislators also rejected Connecticut College’s claim, on the grounds that a private school could not prevent the state from applying its name to its own institution.

Legislation changing the name of CAC to CSC was signed by Wilbur Cross on February 25, 1933.

Then in 1937, state Rep. Samuel Friedman of Colchester submitted a bill, House Bill #82, to the legislature titled “An Act to Establish a University in Connecticut.” According to Walter Stemmons, the university editor who published a history of the college’s first half-century, the bill called for an appropriation of $5 million to buy land, construct buildings, hire a faculty, and provide a broad curriculum of study.

In the public hearings before the Joint Standing Committee on Education, Thomas Clifford, an educator from Colchester stated, “I think we should consider the need for a University of this sort in the state…and I believe if you expand the college at Storrs into a University you will have no trouble regarding the money.” Clifford had suggested the idea of a public state university.

The 1937 bill failed, and in the 1938 election, Friedman was replaced as Colchester’s representative by Edward Seger. Before re-submitting the bill at the start of the new General Assembly session in January 1939, Seger was persuaded to alter the original bill considerably.

A new version, House Bill #1227 was very brief, simply stating that “The name of the Connecticut State College is changed to The Connecticut State University.” That too was changed, and the final bill called for CSC to become The University of Connecticut.

The bill passed both houses of the General Assembly without dissent and was signed into law by Gov. Raymond Baldwin on May 26, effective July 1, 1939.

When I was a senior in high school down in Delaware, more than one person wondered why I was going to school so far away and so far north. I was usually left a little confused – after all, it was only 250 miles north and only 4 or 5 hours away by car. Why the concern? Turns out, my classmates thought I was headed to the Yukon (I’m not joking) for reasons beyond my understanding.

I mention this story because I had heard over the years that UConn settled on a husky dog as a mascot as a play on this apparently common misunderstanding. However, I am very confident this story fails the truth test. When Connecticut Agricultural College became Connecticut State College in 1933, the institution’s athletic teams could no longer be called “Aggies.” The following year, the student newspaper, The Connecticut Campus, conducted a student survey to select a mascot. The top choice was the husky dog. A student contest resulted in naming the dog “Jonathan” for Jonathan Trumbull, Connecticut’s Revolutionary War-era governor.

And as we just learned, the school wasn’t even a university at that time, so the misnomer didn’t even exist yet. Story: debunked (but still cute). The first Jonathan was a brown and white husky. However, all subsequent dogs have been all white. UConn’s current mascot is Jonathan XIII (as of 2010).

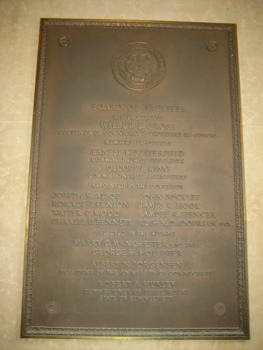

So where does that leave us? Well, visitors to the Wilbur Cross gallery won’t necessarily glean much of what I have provided you here. There is sort of a rotunda room with large wall displays with various narratives about the school’s history. But they seem to have put a premium on “hipness” rather than what someone must have felt was boring history. That’s what my pictures depict here.

There is a history of so called “Huskymania,” which notes that one of UConn’s first national champions was some archer named Jane Weber who won 16 titles in the late 40’s. Also of note: one of UConn’s first organized teams was an ice polo team.

Ice polo?! Yup. In fact, I just Googled the phrase and the first hit was from a UConn publication! Yet another one of those reaffirming moments I experience while writing this website.

Ice Polo!

There were three team sports in Storrs in the 1890s: football, baseball, and ice polo – a game similar to hockey but with shorter sticks and a ball instead of a puck. This photo is of the Storrs Agricultural School ice polo team in about 1891, playing on the Duck Pond (Swan Lake). Ice polo, which developed in the United States, was replaced by ice hockey – which developed in Canada – early in the 20th century. This view looks southeast toward (from left) the Storrs Agricultural Experiment Station, the chemistry laboratory, and Old Main. Behind the windmill of the water well is the rear of Gold Hall, a men’s dormitory. Women began to attend SAS as commuters in the fall of 1891.

So next time you’re discussing random UConn sports facts at the bar, throw that one in the face of the guy with whom you’re talking.

This reminds me of how it always seemed Storrs was about 10 degrees colder and 5 times as windy as the rest of the state. If Hartford gets a foot of snow, Storrs gets two. I was there on a very hot summer day… But as this picture shows, you just never know when it’s going to snow in Storrs. Always good to be prepared.

As I finish this post now a couple days after the get-together with friends I mentioned earlier, I’m reminded about a very unique thing about UConn. All those guys – and all the ones I keep in touch with – lived in Middlesex dorm with me. That was my world and I really had no reason to leave it other than class. Yes, I lived in a dorm until I graduated at the ripe old age of 22. Weird? Yes… But completely normal for UConn. In fact, when I moved into that dorm at 20, I was one of the younger guys at my end of the hall.

As it turns out, UConn has the highest percentage of students living on campus of any major public university in the nation. Heck, most of the (loser) Greek houses are on campus up there. This always struck my non-CT friends as very strange – but it’s just one reason I loved going to school there and living in Middlesex.

That, and the fact that Middlesex was an all female dorm except for our one floor. Word.

Wilbur Cross in the Fall (From UConn Today)

Leave a Reply