A Nice Historic House Museum, Generally Speaking

Middletown (Google Maps location)

May 2011

As you know by now, there are 2,346 historic house museums in our small state. Give or take. Some are fantastic and dynamic; some exist as museums simply because… the structure exists. I take it as a personal challenge to find the unique and interesting aspects of each one to make reading about them somewhat tolerable.

Of course I think all 2,346 (give or take) historic house museums are worth visiting; I don’t mean to imply otherwise. The mighty General Mansfield House Museum slash Home of the Middlesex County Historical is filled with interesting exhibits and worthwhile history.

But really, in the end, it’s just another of our – did I say 2,346? – another one of our 2,346 historic house museums.

This place is important for several reasons. Notably, the house is one of the few residential structures still standing on Middletown’s Main Street. It is old. It was the former home of one General Joseph King Fenno Mansfield, a Civil War hero who died at the battle of Antietam in 1862. The museum had a very large and fascinating Civil War exhibit on display for a few years.

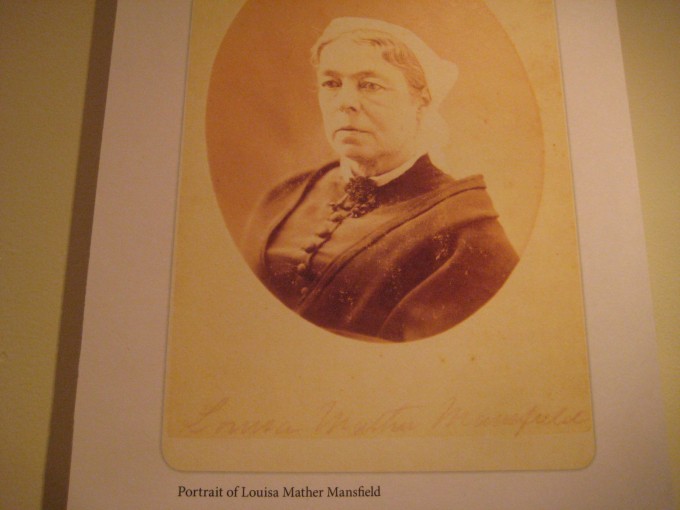

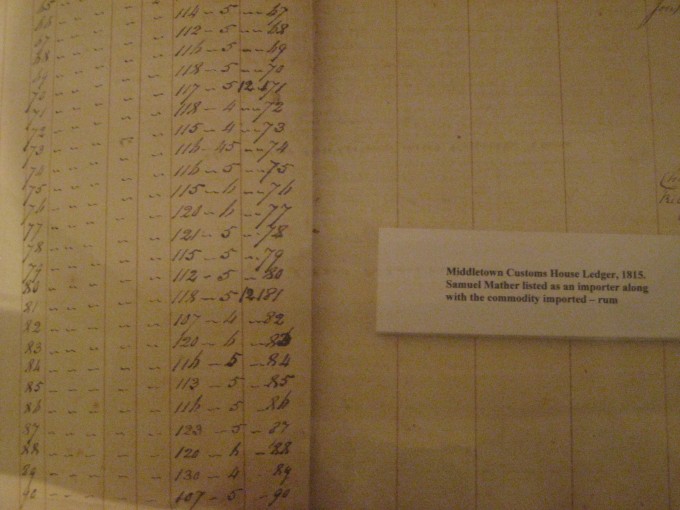

As with all of these places that dot the state, tracing the lineage of its ownership is half the battle. The General Mansfield House was built around 1810 for Samuel Mather, a local merchant. The house was later occupied by his daughter Louisa and her husband, the aforementioned General Mansfield. In due course, the house passed into the hands of Mansfield’s youngest daughter Katherine, who lived in the house until her death in 1918.

In the late 1950s, the house was slated for demolition to make room for a new parking lot. As per the Connecticut Way. But by acting quickly, the Middlesex County Historical Society was able to purchase it from Mansfield’s descendants, thus saving the house for everyone in the community to enjoy for decades.

And now here we are.

The ol’ bullet-stopping bible display. A classic.

The museum contains, of course, a lot of Middletown’s history. I learned a bit of information regarding Middletown that may be as apocryphal as it is interesting: Middletown was named Middletown before Connecticut’s borders were officially set. It was the “Middle” of the Connecticut River trade route between Old Saybrook and Hartford… the fact that it wound up in the middle of the state was pure happenstance. I have no idea how true that is, but it’s kind of interesting regardless. And it would have been funny if, instead of the Connecticut, it was the Housatonic and Newtown ended up being Middletown.

The Mansfield House – via the Middlesex Historical Society – even hedges their bets regarding this:

The Wangunks, a Native American people, had lived at the great bend in the Connecticut River for countless generations when the first English settlers arrived in 1650. The Wangunks called the area “Mattabeseck,” which was incorporated by the Connecticut General Court in 1651 and encompassed the present day towns of Middletown, Middlefield, Cromwell, Portland, East Hampton, and part of Berlin. In 1653, Mattabeseck was renamed Middletown, probably because of its location midway between Hartford and Saybrook.

Emphasis mine.

Incorporated in 1784 but settled by Europeans approximately 150 years earlier, Middletown was initially a settlement based on agriculture and the port that developed along the Connecticut River. The city grew prosperous on a foundation of trade with the West Indies and the produce of farms wrested from the hills and forests. I’m the rare goofball who “completed” the 20-stop Middletown Heritage Trail, which you can read all about here. The Mansfield House makes the cut.

The museum has all sorts of historic Middletown items: the Leatherman’s pipe(!), suspenders made at the Russell Manufacturing Company, once the nation’s largest supplier of men’s braces, and a 1920s steam contraption used by Jack’s Lunch for making Middletown’s most (in?)famous culinary creation, the steamed cheeseburger.

Sorry Middletown and environs, steamed cheeseburgers are gross.

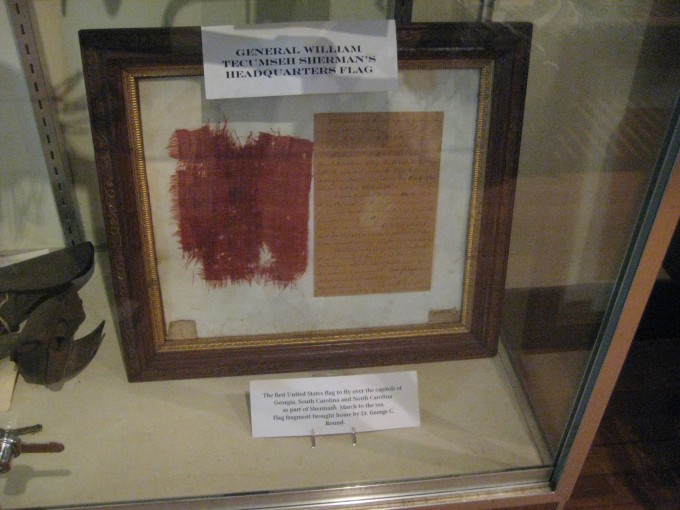

On display was also a piece of William Tecumsah Sherman’s headquarters flag. That was cool… which leads us to…

As I said, the main exhibit during my visit was Hard & Stirring Times: Middletown and the Civil War. (It ran all the way through June 11, 2016.) The exhibit suffered a bit from something my friend Bill Hosley and I have lamented over the years: Verbosity. As one who is guilty of writing far too much far too often, I can sympathize.

But when the walls are covered with lengthy explanations and stories, I feel it detracts a bit from the experience. That stuff is best suited for online reading, not wall reading. (And please know that this place is not alone in this, nor is it “the worst,” for lack of a better term.)

And so, I turn to their website to help us navigate some of what I saw.

Less than a hundred years after the formation of the United States of America, the nation found itself embroiled in another conflict that threatened its very existence. Known by many names, the War of Secession, the Rebellion, the War Between the States, the Civil War lasted for four long years and resulted in the deaths of over 620,000 people, or 2% of the population. In terms of today’s population, this would mean over six million dead.

Men marched off together to war with their fathers, brothers, uncles, cousins, and neighbors while the women and children were left behind to continue the duties of daily life without their menfolk. Explore how this moment in American history affected the men, women, and children of the City of Middletown and continues to impact our lives to this day.

Guns. Lots of old guns.

While the majority of Middletown voters in the 1860 election were Democrats, the Republican party took advantage of their rival’s divisions, and campaigned hard to ensure Lincoln’s victory. South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20, 1860, swiftly followed by the other Southern states. The bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 1861 marked the beginning of armed hostilities between the United States of American and the Confederate States of America.

The exhibit focused extensively on the women left home in Middletown while their husbands, fathers, and sons marched off south to war. However, getting at that information is often tough, as women didn’t really participate in the public arena much back then.

To see what women believed, one needs to look at their private letters and diaries, and then extrapolate from their actions what was essential to them. The proper lady of the 1860’s was supposed to be kind, generous to others, and do good works through their home and their church. A woman of this period was constrained not only by society, but also literally by her clothing. With multiple layers and an understructure supporting the fashionable hoop skirt, a woman had to look for discrete ways to move and influence the world around her.

Yeah, the women of the day were a bit rough around the edges… which makes sense since life was rather hard for several reasons. Many times, it was the women with the liberal (and liberating) attitudes that set some social changes in motion.

Terrifying.

Alma Coe Lyman (1786-1875), described in the Lyman family genealogy as a woman of “strong mind and excellent character,” was a staunch Congregationalist and abolitionist. Her husband, William Lyman (1783-1869), had once been set upon by a mob in Durham for his abolitionist beliefs and she was a lifelong subscriber to the American Missionary, a publication that supported eliminating slavery, educating African Americans, racial equality, and Christian values.

In her letters to her sister-in-law, Sally Miller, Lyman speaks of how “God has long said to this nation ‘Let my people go’ but we have not heed to the command. but strengthened ourselves in wickedness, & practically said who is the lord that we should obey his voice, & now we is giving liberty to the sword, & to the pestilence to furnish if not to destroy us utterly. O that we may repent & do works meet for repentance before it is too late.”

For Lyman, and others of like mind, the war was not about politics and states’ rights, but a scourge from God that would cleanse the wickedness of slavery from the nation.

Her heart was in the right place, even if her reasoning wasn’t.

Mansfield’s wife

Over 950 men from the City of Middletown (from an 1860 population of 8,620) would eventually serve their country during the Civil War. While each came to the decision for his own reason, once a soldier, their lives became intimately tied to their company and regiment. Formed on a regional level, platoons and the larger company would often have members of the same family, neighbors, and lifelong friends among their ranks. The men trained, fought, and died alongside members of their community. This method of recruitment was particularly devastating as a community’s entire generation of young men could be wiped out in a single engagement.

While a draft was instituted in 1862, only 20% of the federal fighting force would be supplied this way. The majority of soldiers volunteered for a three-year term willingly. Rival recruitment offices opened in Middletown and competed for able bodied men between the ages of twenty and forty-five. Bounties were offered by the city to fill enrollment requirements and were advertised on broadsides, in the newspaper, and even on flour sacks.

Connecticut River ship logs.

The exhibit featured many old photographs and newspaper articles and touching tributes from home. It was immersive and told the tragic story on the national and local scale. It was very well done and lasted for 5+ years as the semi-permanent exhibit for a reason.

And, of course, General Mansfield’s own participation in the Civil War is an even bigger reason. He died at the Battle of Antietam, but this bit from the museum’s website is worth reading. War is hell.

The Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest day of the Civil War, began early on the morning of September 17, 1862 in Sharpsburg, Maryland. Joseph Mansfield, a 58-year-old General in the Union Army, waited anxiously for the signal to lead his ten thousand troops into the fight. When “Fighting Joe” Hooker called for support, Mansfield urged his men forward into the thick of the battle.

As he raced about the battlefield on horseback, Mansfield realized that some of his soldiers were firing into a wooded area which Union troops had occupied just minutes before. Immediately he charged forward, waving his hat and shouting for the line to cease firing. A soldier later wrote that the General “was in a most perilous position…The bullets and missiles were flying like hail and no one upon horse could survive…It seemed as if the very depths of pendemonia had sent their furies, and such a tornado of missile screaming through the air baffles all description.”

While Mansfield rode through the heavy fire, trying to keep his men from firing on what he believed were Union troops, his own soldiers called to him that he was misinformed. The General brought his field telescope to his eyes, and made out the gray coats of the Confederate Army. “Yes, you’re right,” he conceded. At that moment his horse was shot and began to thrash about. As Mansfield dismounted to lead him, his soldiers noticed blood streaming down the General’s chest. A Confederate bullet had pierced his lung—a fatal wound.

Several soldiers carried Mansfield to the rear, slung in a blanket. He murmured, “I shall not live! Oh! My poor family!” Twenty-four hours later, General Mansfield expired.

But his name lives on, not just with his house museum, but in the annals of olde timey baseball as well.

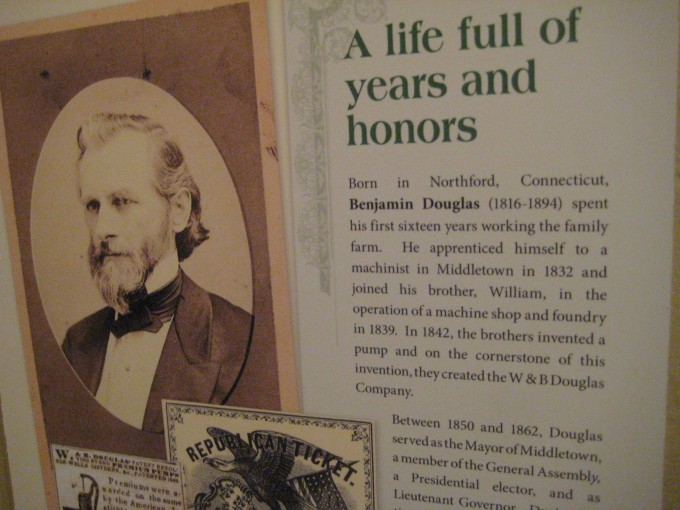

At the house, there is also a little display about baseball. Baseball flourished in America after the Civil War. In 1866, local baseball enthusiast Benjamin Douglas, Jr. organized a team called the Middletown Mansfields, honoring the city’s Civil War hero. In 1872, the Mansfield’s briefly turned professional, playing in the National Association (the forerunner to the National League). They disbanded towards the end of their first season, citing financial woes.

One guy, catcher Jim O’Rourke, was later inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. I just found this nugget about him:

“Sept. 3, 1883. Catcher Jim O’Rourke, the sweet smiler of the Buffalos, had his hand split and a finger knocked out of joint in the Buffalo-Chicago game of Aug. 16 at Buffalo, but a fair little damsel was on the stand, and he had too much nerve to weaken in her presence, so he pluckily caught the game out with his pockets full of tears.”

Mansfield’s old tape measure, for good measure

Pretty sure General Mansfield wouldn’t have had much sympathy for ol’ O’Rourke.

While you can’t visit the Civil War exhibit anymore and your Mansfield House experience will be different from mine, you should still go. Middletown is one of Connecticut’s larger cities, has a world class university, and it seems to be on a bit of an upswing as far are restaurants and new businesses go.

![]()

Middlesex County Historical Society

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Leave a Reply