This Place is Fly

New England Air Museum, Windsor Locks (Google Maps location)

April 2012

The New England Air Museum (NEAM) is a monster. Easily one of Connecticut’s largest museums, writing up a visit is daunting. Writing up a visit with a tired and difficult Damian is impossible. So, dear readers, I’m sorry. I’m sure that this page will gloss over some really cool and important stuff. I’m also sure every synopsis of every visit you’ve ever read has glossed over some important and cool stuff.

I should also add that the subject matter is one which I don’t know much about. And, to wrap up my caveats and disclaimers – the most frustrating thing about this page is that I had an enormously competent, wonderful, and attentive guide: Susan Orred, who is a veteran in the local museum scene. She has been a CTMQ reader for years and was aware of Damian’s limitations before we even met. This lifted a burden off of me, simply because NEAM is so huge and I’d love to see it all, but in a unique CTMQ way. Susan was more than accommodating to both Damian’s – and my – special needs.

Due to its size, NEAM is seriously impossible to write about in any coherent way. The museum is actually overseen by The Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Society which was founded in 1959. This was essentially a group of guys who knew how to fix planes. 20 years later, they moved into a building that was summarily destroyed by the infamous 1979 Windsor Locks tornado. 22 years later, in 1981, they moved into the present location, just outside of the Bradley Airport perimeter.

And that’s where they remain to this day. NEAM houses one of the world’s most outstanding collections of historic aviation artifacts: more than 80 aircraft and an extensive collection of engines, instruments, aircraft parts, uniforms and personal memorabilia.

Stop reading for a second. Eighty aircraft. EIGHTY! And it’s not like 75 of them are just some little clunky piper planes that no one cares about. Not at all.

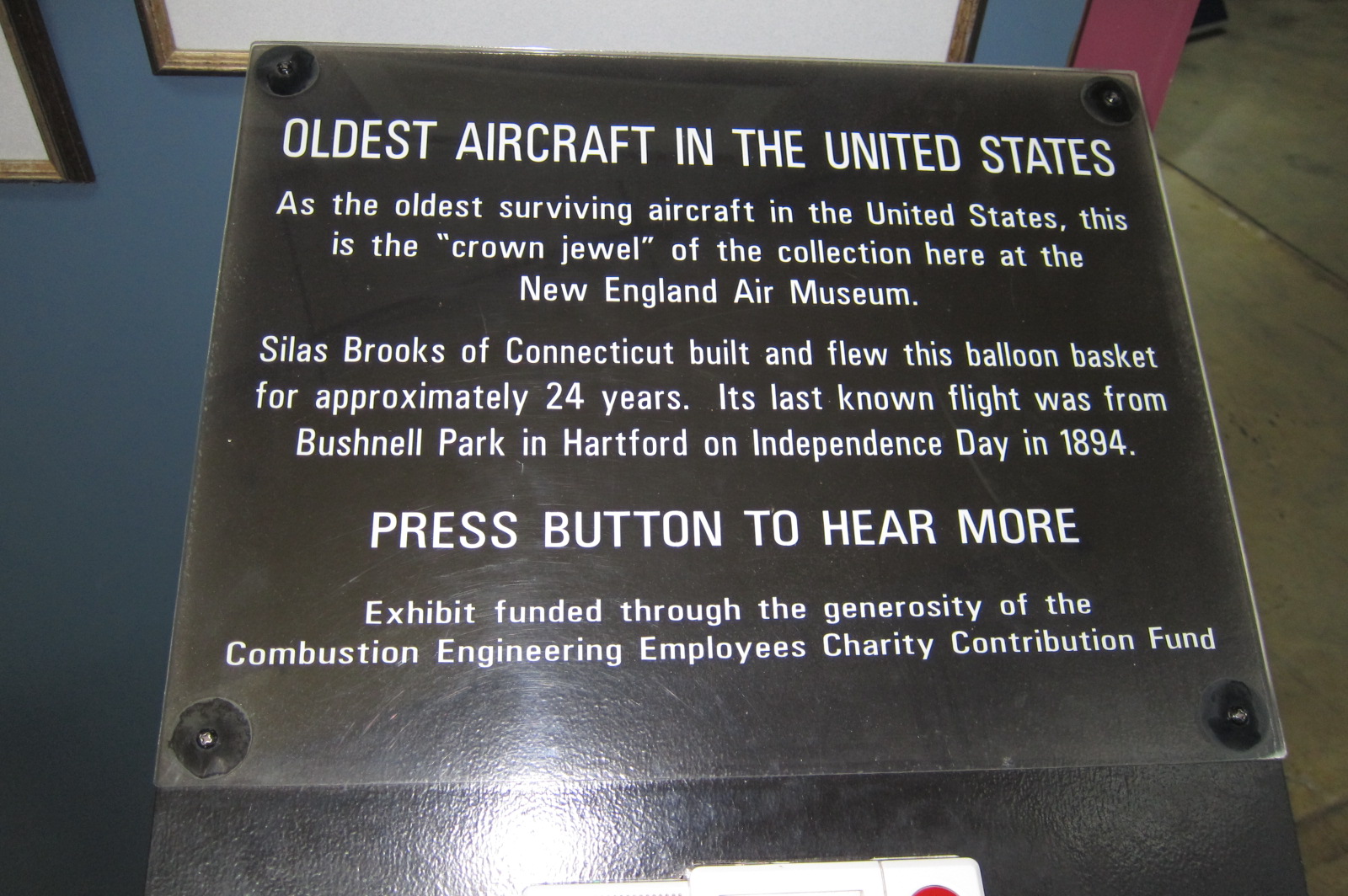

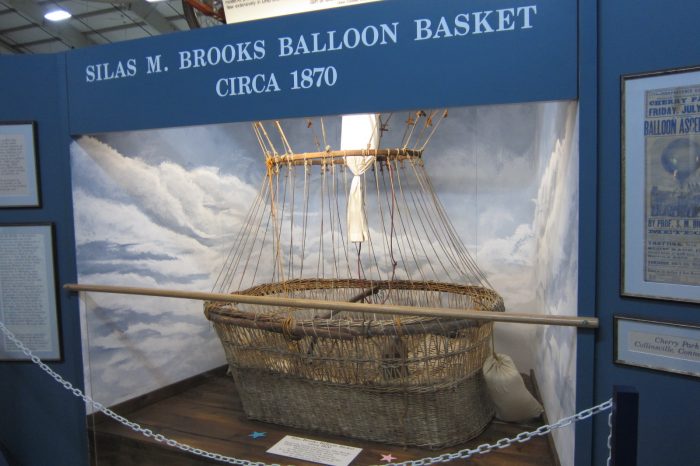

Within this collection are the last remaining four-engine Sikorsky VS-44A, donated by its previous owner, actress Maureen O’Hara and restored to original condition; an expertly restored B-29 Superfortress; Silas Brooks Balloon Basket (1870) believed to be the oldest surviving aircraft in the United States; the Bunce-Curtiss Pusher (1912), the oldest surviving Connecticut-built airplane; the Sikorsky S-39, the oldest surviving Sikorsky aircraft; and a Kaman K-225 helicopter, the oldest surviving Kaman-built aircraft.

Whoa.

I just had the thought that the guys who run the NEAM went all around the world destroying old Sikorsky and Kaman aircraft in a bold effort to make the multiple claims of “oldest surviving” in their own museum. Now that would be a story.

Anyway, a couple of the planes mentioned above are massive. Restoring them required Herculean efforts. The B-29 super-fortress bomber (1944) and the Sikorsky VS-44a are probably the two most impressive planes. The B-29 sat outside, exposed to the elements, for decades and was nearly destroyed by the aforementioned tornado before being completely rebuilt by NEAM volunteers.

Originally built in Bridgeport, the VS-44 had an impressive career that spanned WWII, post-war trans-Atlantic passenger service, and niche services to Iceland, South America, Catalina Island, and the Caribbean. In 1968 it was damaged after running aground in St. Thomas, where it was abandoned and suffered from extensive exposure to the corrosive tropical environment. It was at last brought back to Connecticut and completely refurbished by a team of more than 100 retired Sikorsky workers, many of whom had originally helped build it. Volunteers logged more than 300,000 hours during the 10-year restoration project.

That’s pretty awesome. If you’re curious, whenever I quote something like above, it means I lifted it from elsewhere. This is necessary at places like the NEAM. See, watch:

In the same giant hangar where the VS-44 is now on view, another great airship is being restored by its own dedicated team: the command car of a 252-foot-long Goodyear K-Class blimp built in 1941? 42. The K-28 was one of the original airships with which Goodyear pioneered the technology of illuminated aerial advertising that is now a familiar presence over cities and sports stadiums around the world. But Goodyear originally manufactured the K-Class blimps for the United States Navy to escort Allied convoys and search for German U-boats off shore during World War II. With a crew of 10, these massive, helium-filled sentinels carried radar, sonar buoys, aerial bombs, and a 50-caliber machine gun for self-defense. All of this equipment was later stripped out as Goodyear put the blimps into civilian use.

After the K-28’s retirement and ensuing decades of deterioration, NEAM volunteers spent more than two decades meticulously researching and restoring the last surviving example of a U.S. Navy K-Class blimp car to its original configuration. This required finding two replacement Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines and their Hamilton Standard propellers, creating new aluminum engine cowlings, and refabricating dozens of missing Plexiglas windows and much of the interior, including crew stations and bunks, replicated galley, navigation and radar equipment, sonar buoys, bombs, and the machine-gun turret. Although the restoration will not be completed for at least another year, visitors can watch its progress.

NEAM is the type of museum that almost requires revisits. I encourage you to do so. That way, you can engage in one of Connecticut’s pastimes: Arguing about historical stuff with no final answer.

Yes, we all know of the Windsor vs. Wethersfield “which town is older” argument (The answer is Windsor). And then there’s the Pepe’s vs. Sally’s vs. Everyone else argument (the answer is Sally’s). And, perhaps a bit lesser known, there’s the Gustave Whitehead argument.

If you’re unfamiliar, Bridgeport’s Gustave Whitehead was the first person to successfully fly an airplane. Or not. This claim is made in other Connecticut museums and I’ve read it many times over my years of writing this website.

However, the NEAM takes a pretty strong stance on this controversial matter: The Wright Brothers deserve their fame and notoriety as the first airplane fliers in history. The Smithsonian has studied this whole thing and take a strong pro-Wright stand as well. (NEAM is merely following their lead, I think. And really, why wouldn’t they?)

Let’s keep going further back in history though. There were flying machines before the Wright Brothers. And the NEAM has some of them too.

A large, wicker balloon basket is believed by the museum to be the oldest surviving, intact aeronautical artifact used in the United States. This basket is a relic of the adventurous career of Connecticut inventor and showman Silas Markham Brooks, whose career as a balloonist reached great heights before he plummeted to obscurity in old age. With 187 known balloon ascensions, this man is arguably Connecticut’s foremost air traveler of the 19th century.

See, now, I had to blockquote that bit from Connecticut Explored because no way would I write the “reached great heights before he plummeted” bit. But having now read the entire linked article, it is true.

Brooks led a rather crazy life; full of exploits and famous people and travel. But he died in obscurity and poverty. At least his basket has been restored and his story is now being told in Windsor Locks.

And what the heck. Let’s go even further back in time and check out the Blanchard basket replica. Constructed and flown in 1993 to mark the 200th anniversary of the first manned flight in America made by French aeronaut Jean-Pierre Blanchard in Philadelphia, they’ve got it here:

Now that we’ve gone all the way back, let’s start moving forward in time again. Hoo boy, where to begin? Let’s bump things up to 1910 with a model of Edson Gallaudet’s steam powered airplane. It looks like a mess to me too, but Gallaudet was yet another aviation pioneer from Connecticut. This is the second-oldest surviving example of Gallaudet hardware – the oldest being his 1898 kite-gliders which is at the National Air & Space Museum in Washington DC.

Eh, you know what? The NEAM is just so huge with so many planes and engines and whatnot, I’m going to copout here and just post a bunch of pictures with captions. Something tells me none of you are going to care. Let’s do it!

The B-29 Superfortress “Jack’s Hack”

I lied. There’s a lot to this plane! There are less than 30 B-29s left in the United States. The B-29 was acquired by the Museum from the Army Proving Ground in Aberdeen, Maryland. The B-29 restoration began about twenty years later, when it was moved into the Restoration Hangar. Between 1998 to 2003 the engines were removed, disassembled, reassembled, the aft and tail section cleaned and restored. The instrument panels, seats and tail gunners section and the engine nacelle accessories were removed and cleaned. The propellers were sent to Hamilton Sundstrand for overhaul. It’s now around 98% complete as the museum is still looking for a few parts.

Let’s try again…

Doman YH-31, built in Danbury. It had some features on it that propelled helicopter design forward.

1935 Ford Roadster for some reason. Less than 5,000 of these cars were ever made and my wife would love one.

Sikorsky. Helicopter. Synonymous.

I think this is a Stinson 105 that was used during WWII by the Coastal Patrol, but it looks like a toy.

In case anyone was wondering, there’s lots of stuff to read here as well.

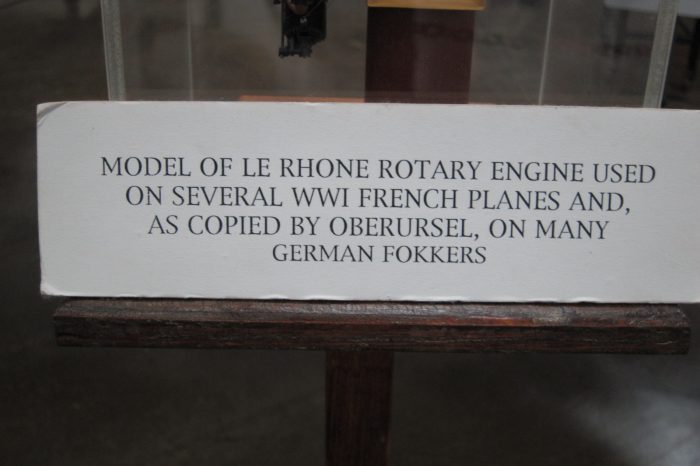

There are also lots of engines to look at for all of you who enjoy looking at engines.

Track pants dad helping track pants son virtually fly a Cessna

And bombs. There are bombs too. Such prettily painted bombs.

NEAM has “Open Cockpit Days” that allows for kids to get behind the wheel of a bunch of different planes. Those are really cool events.

Lots and lots of planes

This is a Grumman Turret from 1943. It represented a leap forward in turret technology but I just like how the gunner sat in a glass bubble.

Sikorsky S-16 from 1915 (Replica). These planes were flown by the Russian Air Force in WW1.

LOL

I would drive this truck

Grumman F-14 Tomcat… which can reach 60,000 feet of altitude in 2 minutes and 6 seconds which is bonkers.

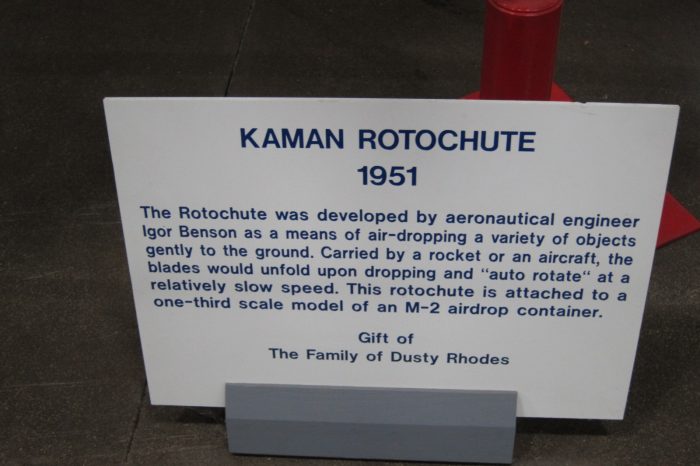

If you ever wonder how much I read at museums… RIP Dusty Rhodes.

I don’t remember what this was about

There are planes outside as well.

And spacemen!

And space toilets!

And Damian!

Okay, that’s more than enough. There are a million other opportunities to take pictures of cool stuff here. Too much if you’re trying to explain all of it on a website for people to read.

For example, I could spend time on this page telling you all about the Hamilton Standard Hydromatic Propeller on display here:

After all, it is an American Society of Mechanical Engineers National Landmark. There are two of them here! Fortunately for y’all, I’ve chased them down and written up.

I’d like to thank Susan for the accommodating tour she provided and for answering all my (probably) weird questions. Because of Connecticut’s hugely important role in aviation history (and present… for the present), NEAM is a trove of cool artifacts and great information. My dad would likely spend an entire day here… that’s a warning to all of you with dads like mine.

Just kidding, I could spend an entire… half a day here myself. And you should too.

![]()

New England Air Museum

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Leave a Reply