Putting the Ire in Ireland

Hamden (Google Maps location)

June 14, 2014

This museum officially closed in 2021 but not without controversy. It may reopen in Fairfield.

This museum was part of the Connecticut Art Trail.

I have a whole massive list of all the stuff in Connecticut that is the oldest or largest or the only in the US. The list grows every more often than you’d think. Like today. Right now I just learned that Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, located in Hamden just over the New Haven line, contains “The world’s largest collection of Great Hunger-related art.”

Now we know. And for you Irishphiles, Connecticut used to have the store selling the largest amount of Irish goods in the western hemisphere in Farmington… until it closed in 2019.

As depressing as the closing of O’Reilly’s Irish Gifts is, the theme of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum is more so. But the somber nature of this place is important and necessary – especially here in Connecticut where so many Irish immigrants ultimately settled.

Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum preserves, builds and presents its art collection to stimulate reflection, inspire imagination and advance awareness of Ireland’s Great Hunger and its long aftermath on both sides of the Atlantic.

There are a lot of depressing museums in Connecticut, but the others are all depressing simply because they are underfunded slightly sad little affairs. The Hunger Museum is depressing because it’s supposed to be depressing. And, of course, enlightening and impactful. (This isn’t the only museum like this by the way. I left the Palestinian Museum in Woodbridge on the verge of tears.)

The museum is actually under the auspices of Quinnipiac University. Even pre-pandemic, there were rumbles of its imminent closure, but as so often happens in such situations, wealthy interested parties (or whatever) came to the rescue and as of now, the museum continues forth.

I’ll admit, the laser focus of this place struck me a little odd. I’m not well-versed in the Irish Famine, and was expecting more history surrounding that. And while it’s there, the museums focus is more the Famine’s impact through art.

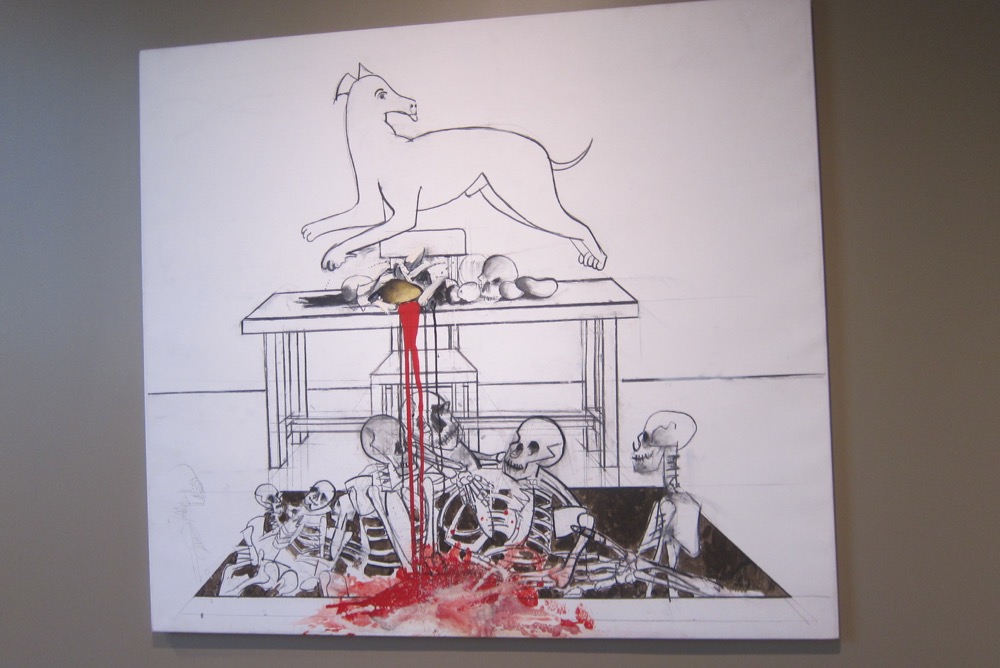

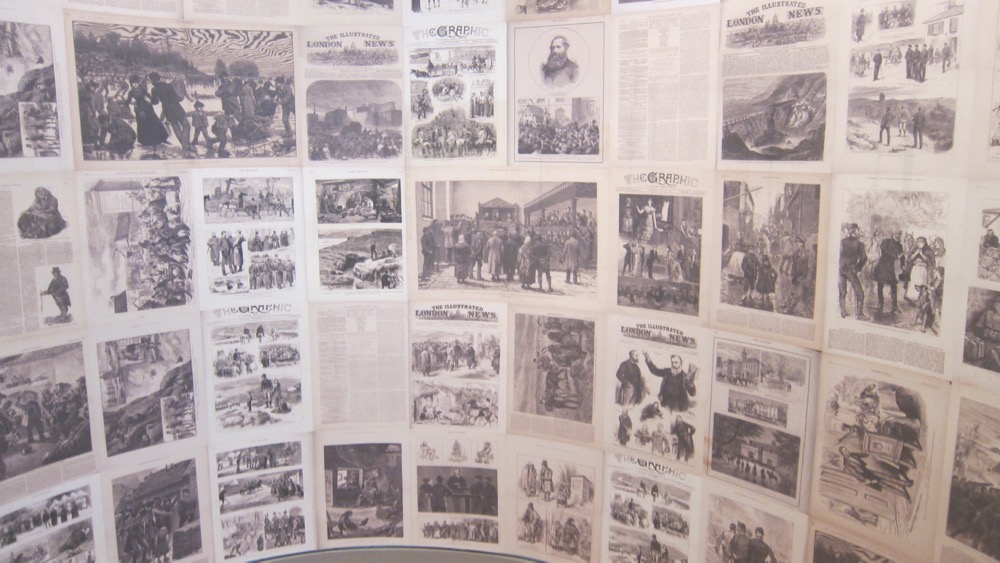

The museum interprets the Famine visually, allowing artists — both those contemporaneous with the Great Hunger and those working today — to explore the impact of the loss of life, the leeching of the land, and the erosions of language and culture. Through its display of outstanding historical and contemporary images, layers of history are peeled back, to uncover aspects of the Famine indecipherable by other means.

I went for a history lesson and got it – sort of – through art. Which, now that I reflect, it’s a pretty cool way to learn about an important cultural touchstone for the Irish culture. I got tired of my oh-so-Irish friends – too many to count – who would fall back on that tired trope of “Oh, the blacks and central Americans who are whining that they have it so bad in American now – the Irish were denigrated and discriminated against back in the day too!”

While that’s all true, that’s a discussion for another day. (Irish people were white. And spoke English. And were legally allowed in immigrate in vast numbers. And… never mind.) Irish folks certainly went through some serious difficulties. I mean, not slavery difficulties, but… I digress. Sorry.

As I was saying, Ireland went through some stuff. During the 16th and 17th centuries, England conquered the island a few times. Oliver Cromwell, whose name is honored by Connecticut’s own Cromwell (yeah, it was supposedly named for a ship named for Cromwell, not Cromwell himself, but that may be Englishwashing history), killed tens of thousands of Irish and drove hundreds of thousands more off their land in what is now Northern Ireland.

These were the Irish-Catholics (pretty much). They were forced to relocate west to rocky and barren land. Land that only supported potato farming. England then offered the nice land to Scots and English Protestants. (I suppose I should now disclose that my personal family ethnicity is Scots-English-German… and Protestant. But it’s not like I identify with any of that myself.)

This, of course, made Northern Ireland (or Ulster as it was – and still sort of is – known) a Protestant enclave on Catholic Ireland. This was in the 1600’s, even though it still causes strife today. The final insult occurred in 1695 when England enacted a series of Penal Laws that denied civil and human rights to Irish-Catholics, and for all practical purposes outlawed the Catholic religion in Ireland. Ireland’s Gaelic language also was outlawed. Unconscionable.

Another hundred years later, England abolished the independent Irish Parliament and officially made Ireland part of the United Kingdom. During that period, Ireland suffered the Great Hunger in 1845-52. (And in 1921, the non-northern counties became the independent Republic of Ireland and the northern bits stayed part of the English-ruled United Kingdom. And it’s not like that made everything hunky-dory, even to this day.

Since I can’t really say much about the art on display – nor can I promise that what I saw in 2014 will be there whenever you visit, let’s learn a bit more about the Great Famine. (They don’t call it the Potato Famine in Ireland, by the way.) Of course the whole tragedy is more complicated than any explanation you’ll find here, but I’ll try to distill it.

Ireland was ruled by England, who had shown that they didn’t really care about Irish people, let alone Irish Catholics. When the potato blight affected crops on Ireland and around Europe, the government didn’t care. Since Ireland was so dependent on potatoes thanks to being pushed out to the rocky lands, they were massively affected. And since their government did nothing to help them, they were decimated.

The most severely affected areas were in the west and south of Ireland (note again: not the northeast where Scots and English lived off the best farmland). 1847 was the worst year and became known as “Black ’47”. (Hey fans of the band Black 47, now you know!) During the Great Hunger, about 1 million people died and more than a million fled the country. Over the course of the decade between 1845 and 1855, no less than 2.1 million people left Ireland, primarily on packet ships but also steamboats and barks—one of the greatest mass exoduses from a single island in history.

The potato blight has been attributed to about 100,000 deaths on mainland Europe, which pales in comparison to what happened in Ireland. And of course, countless Irish emigrated to the young United States; to the tenements and factories of the growing country. As they all came through New York, most settled between there and Boston. And yes, we’re well aware of how Irish you are, Boston, thanks.

The bottom line is that the Great Famine could largely have been avoided had the British Parliament and England lifted a finger to help the Irish population. Do Irish Catholics have a good reason to hate England to this day? Yes. Enough to commit acts of terrorism during our lifetime? Ehhhh, I’m not cool with murdering innocent people.

Which brings us to… Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum. It is a beautiful space and evokes just the right amount of somberness and celebration of Irish culture. I didn’t know what to expect going in, and came to better understand and respect the telling of the famine through art.

Visual artists are artists because they tell stories through works rather than words. A painting or piece of sculpture can often create more emotional impact than any 1300-word essay… let alone this one. So I’ll stop now and simply say that Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum is worth visiting and it is one of the more unique and important museum out of the hundreds in our small state.

![]()

Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum

CT Art Trail

CTMQ’s Firsts, Onlies, Oldests, Largests, Longests, Mosts, Smallests, & Bests

Leave a Reply