HangArn a Minute!

East Hartford (Google Maps location)

May 2019

Connecticut museum visit #414.

Visiting has become much more difficult now, with a badge-access campus.

After I left my job at LEGO in late April 2019, I had a few weeks before starting at my new place of employment. With some free time, I did what anyone would do and began seeking out a bunch of museums that are only open during weekdays.

This one, the Hangar Museum on the Pratt and Whitney campus in East Hartford had been on my wish list for years. Only open during the day on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, I’d never been able to get to it before. This was my chance.

And so, I hit the road for the short drive across the Connecticut River to check it out. I had never been on the international aerospace giant’s campus before. I mean, I thought I had, having gone to plenty of UConn football games at Rentschler Field next door (officially named Pratt and Whitney Stadium at Rentschler Field… until UConn gives up the big time dream anyway), but I was mistaken.

The campus is huge. Serpentine roads and access gates and general confusion reigns here. As you’d imagine, security is tight, I was able to drive through any and all gates at will and just sort of get lost in the maze of buildings and parking lots. Note to P&W: Do you let every middle-aged white guy in a Subaru with no credentials drive right through every access gate? Just curious.

Raytheon bought P&W and all its subsidiaries so maybe now it’s a bit different.

Hey, I’d just left LEGO where anyone can walk into the North American headquarters and poke around – which I always felt was odd considering intellectual property theft is a huge issue for the company.

I finally found the building that houses the museum. It doesn’t really look like a hangar, but I guess this is what hangars looked like a century ago. If you go, find this building – the original 1920’s hangar.

Walk up to the lone door that doesn’t look like much and certainly has no signage. Open it and… voila. You’re in. There is a little lobby area and past that, a huge (yes) hangar. The space is used for company events and the museum – at least during my visit – was sort of pushed to the four sides of the massive room.

A random guy told me that everything had recently been moved for a big event and it was a bit of a jumble, but that’s fine with me. It’s not like I’m really jonesin’ for hours and hours of jet engine history. After all, there are several other museums in Connecticut I’d already been to that handle that as well.

And if you’ve not gleaned this already, this museum is simply a collection of engines spanning the history of the company. Of course, the history of P&W is storied, impressive, and long. It got its start on Capitol Avenue on the edge of Frog Hollow in Hartford and moved to East Hartford tobacco fields just before the Depression. Its first ceremonial groundbreaking here was July 16, 1929.

Andrew Wilgoose

Back then, the offices and factory buildings — still the core of the Pratt complex on Main Street — cost $2 million, or about $27 million in today’s dollars. The complex reached a size of 6 million square feet, with 40,000 employees during World War II. Today it’s about 4 million square feet after some demolitions – and a football stadium and acres of parking lot over the former airstrips. But don’t cry for the company, as it has about $15 billion with a b in sales annually these days.

By the time of the move to East Hartford, Pratt needed space not only for its own operations but also for a remarkable collection of companies from in and out of Connecticut that were coming together as United Aircraft and Transport Corporation: Pratt, Boeing, Hamilton Standard, Sikorsky, two other aircraft makers and three air carriers that would later become United Airlines.

I’ve always been fascinated by the collection of companies associated with Pratt over the years. It’s pretty crazy when you think about it. UTC isn’t even spiked out in the previous paragraph and they alone are a collection of a ton of giant companies. It’s too much of a mess to sort out here, as we have a bunch of old engines to see!

The museum began as a tax-saving accident. The company had stored the old engines in a back corner somewhere for years, then moved them into a storage facility. Some wonky accountant noticed they were paying a lot of storage and property tax, so it was decided to scrap everything.

Someone else said, “let’s declare them as museum pieces,” saved them, and moved them into the empty hangar – made empty because the private UTC airport had recently closed. That’s how the museum was born – as a “museum.” This is probably also why it’s a) still not really a museum in the classic sense, and b) is only open when it is.

Back in the lobby, there’s a portrait of one Mr. Charles Lindbergh who worked with the company back in the day. His desk is there as well as a cool lamp made from engine bearing compartment parts. I bet that retired Pratt engineers salivate over this lamp.

As if that weren’t enough, arguably the greatest thing the company ever made has star billing here: the R-1340 Wasp A Engine. Aircraft engines, considered unreliable during the first 20 years of aviation due to their need for liquid-cooling, heavy weight and other inconsistencies, were given a revolutionary boost with the development of Pratt & Whitney’s R-1340 Wasp Radial Engine in 1925. The engine recently was awarded the lofty status of being an American Society of Mechanical Engineers National Landmark.

Engineers led by Chief Executive Officer Fredrick Rentschler, Vice President of Engineering George Mead, and Chief Engineer Andy Willgoos implemented a number of improvements: a single piece master rod allowed the engine to operate at a higher number of revolutions per minute, producing more horsepower; a two-piece crankshaft able to maintain required tolerances – making the single piece master rod possible; and a split crankcase with two identical halves. This improve the engine’s manufacturability, reducing assembly time and complexity.

These innovations set a new standard for aircraft engine reliability, impacting commercial aviation and transcontinental mail service, and leading to more advanced aircraft in the late 1920s and early 1930s – such as the Boeing 247. Over 90 versions of the R-1340 engine are in operation today.

The first Wasp engine

It’s really the thing that put P&W on the path to massive success, as it revolutionized flying. Period. (If curious, yes, I do, in fact, have a page about my visits to Connecticut’s other 8 ASME Landmarks.

Boeing designed the model 247 around the Pratt & Whitney Wasp and made the case for civil aviation. In other words, it wasn’t until this engine design was created at P&W that regular schmoes like me could fly. Let’s move into the hangar itself.

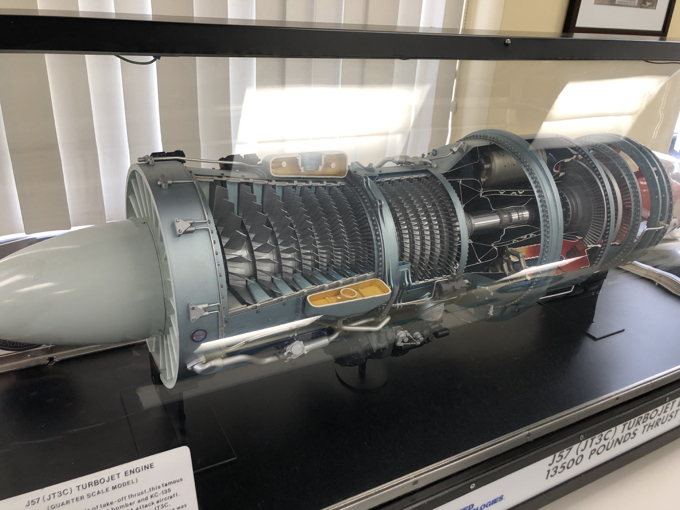

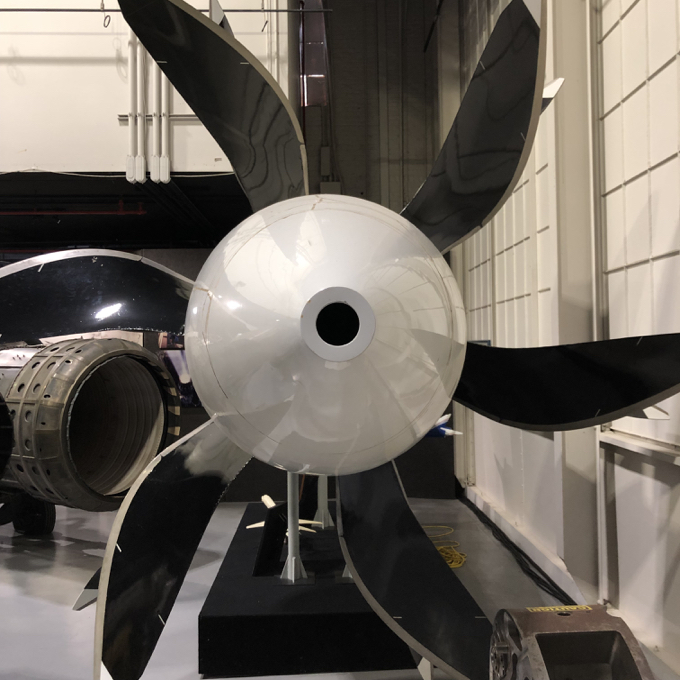

The P&W Engine Museum is loaded with originals and one-of-a-kind experimental engines and engine parts.

I found a couple pages about this museum and its engines by a guy named Al Weaver who worked at P&W during its mid-century heyday. I found this bit fascinating:

I remember the highly classified J58/SR-71 project where even the shipment of the engines was secreted from the public eyes. We used to cover the engines up on a truck and ship them at night to an Air Force base. We didn’t use escorts at first since that alone might attract attention. But one day one of the truck drivers took a back road and ran the engine into a low railroad bridge, attracting all kinds of unwanted attention.

There was an engine project from which no parts have surfaced for viewing. I remember working on parts that had a giant afterburner that I could stand in without touching my head. At the same time there was what looked a burner section full of tubes that formed a heat exchanger. As a teenager I used to follow the manufacturing worksheets from department to department just to find out where the parts I was making finally ended up. Once again Internal Security became very suspicious of me and I later found out that they had the FBI investigate my high school years. I never could find out where that afterburner went. In later years I discovered test results for a small turbine that went with this project (much too small for such a large afterburner) that apparently connected to a large compressor via a gearbox. To this day I really don’t know what this was, but suspect that because of the heat exchanger it was part of the secret nuclear engine program.

If you care to see 50 billion pictures of the various P&W engines with proper titling by a guy who knows what he’s talking about, go here.

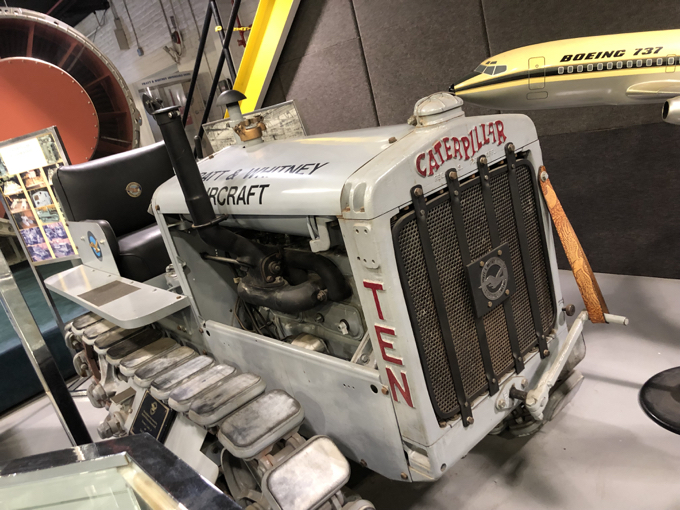

As for me, I wandered around the perimeter of the room looking at the engines. Lots and lots of engines. Walking clockwise, they were more or less in order of development. Every once in a while, there’s a random thing thrown in. Like this, a Caterpillar Model 10 Tractor:

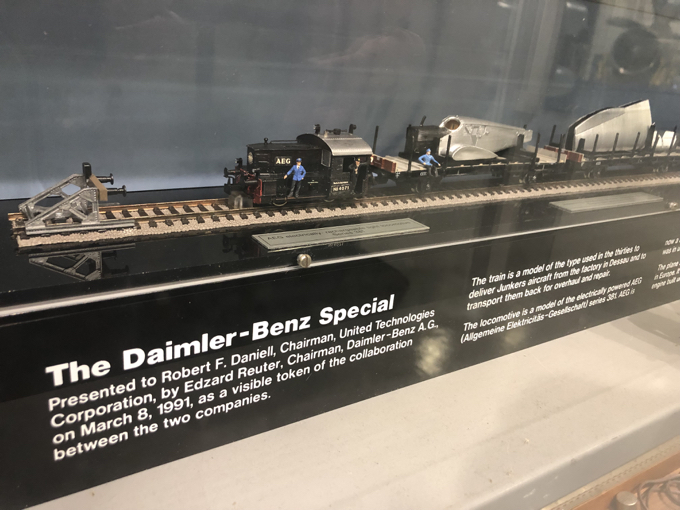

This old thing was used to help build the plant in East Hartford. Sort of incongruous among the jet engines, but whatever. There’s also a model train given to the company by Daimler-Benz depicting the trains transporting junker plans in Germany in the 1930’s.

Apparently P&W was working with Daimler back then. And then P&W provided engines for 10’s of thousands of fighter jets and bombers that killed 10’s of thousands of Germans ten years later.

Such is life.

And death. Lots of death.

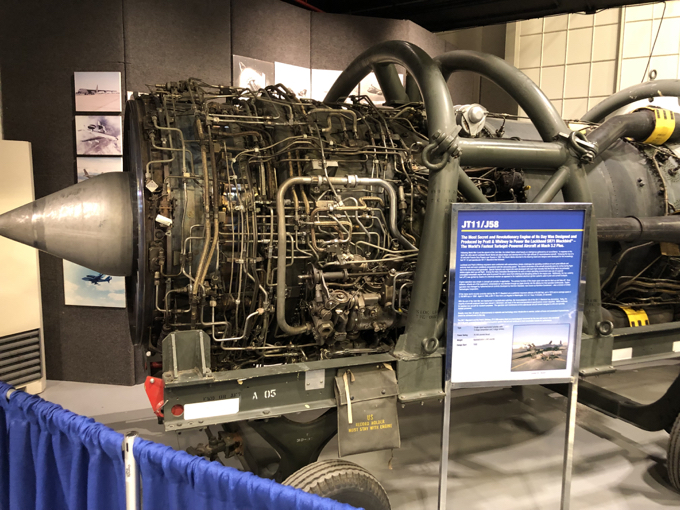

Moving on to the really exciting stuff, like the top secret JT11/J58 engine. This bad boy powered the Lockheed SR71 Blackbird – the world’s fastest turbojet-powered aircraft at Mach 3.2 plus. (That’s about 2,500 mph.)

The SR-71 was developed in the early 1960s in response to two U-2 spy planes getting shot down — one over the Soviet Union and one over Cuba. In addition to its supersonic speed to evade missiles, the SR-71 could fly as high as 16 miles above the earth.

The Air Force officially retired the SR-71 in 1990, but NASA would use two of them for research until 1997. Lockheed Martin is currently developing a successor to the SR-71 Blackbird, the SR-72, which may be tested in 2020. I’m not exactly a fan of war and destruction, but these engines and planes are quite impressive. The engineering challenges of high altitude, extreme temperatures, and extreme speeds had to be overcome.

According to the museums’ signage, the planes “grew” six inches during flights, due to the conditions. And my brain grew six inches learning about all this jet engine history.

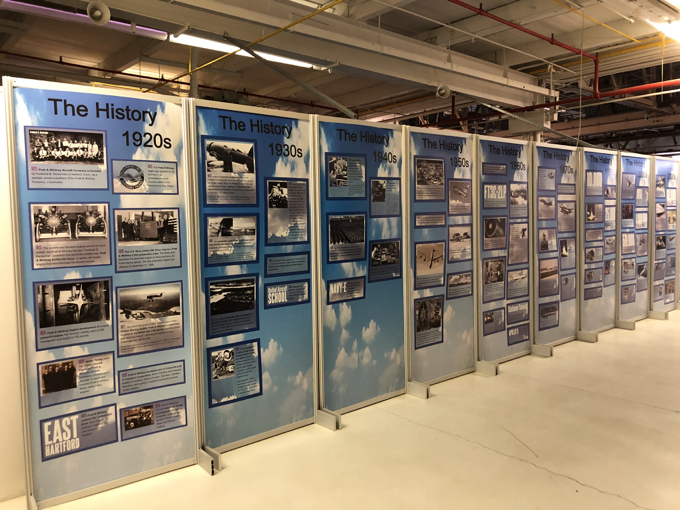

There is a big panel showing P&W’s long history and impressive accomplishments and inventions. The company is hugely important to Connecticut and even pinko pacifists like myself recognize its importance to America’s (good) war efforts in the 1940’s and 50’s, the questionable war efforts in the 1970’s, and the stupid war efforts after Vietnam. They’ve also been quite a big player in commercial aviation as well.

There you have it, the Pratt & Whitney Hangar Museum. Go there on your next mid-week day off from work. If, you know, you’re into this stuff.

![]()

Directions to the museum

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

JOhn Kessler says

JOhn Kessler says

February 16, 2021 at 9:31 pmDo you have any pictures of the XT-57 turboprop?

Jeff Field says

Jeff Field says

March 28, 2021 at 6:29 pmI worked there in 1975. I was a tin knocker in their experimental sheet metal department. Until I discovered your post here, I was unaware of this museum. If you are old enough, you may remember a specialized hangar at BDL that had a cutout in the hangar door where the empennage. Of a B-52 protruded. This was P&W’s engine test aircraft. The story that went around the department was that the previous test aircraft was a B-17. One day, they lowered an engine from the bomb bay but could not get it back up and had to drop the engine in long island sound. This B-17 went on outside display at The New England Aviation Museum, where it was damaged by the 1979 Windsor Locks tornado https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Windsor_Locks,_Connecticut,_tornado

She then went to to Florida for restoration to air worthy condition. She flew until a 2011 engine fire caused a forced landing in an Illinois corn field. All the crew and passengers got out. She is currently undergoing yet another rebuild.

JOHN PERELLI says

JOHN PERELLI says

January 12, 2023 at 6:11 pmNICE STORY BUT ONE THING IS MISSING THE MUSUEMS FOUNDERS NAM THE START OF IT ALL WHO,S NAME HAPPENS TO BE MR DENNIS GROUT HE STARTED THE MUSUEM UP AFTER FINDING SOME OLD STORED ENGINE CONTAINERS ON THE FAR SIDE OF THE RUNWAY IN EAST HTFD CT OPEND THEM UP OTHERS WANTED TO TRASH THEM BUT HE PURSUADED THE HIGHER UPS TO KEEP THEM FOR FUTURE DISPLAY WHICH BECAME THE PRATT MUSUEM MR GROUT WAS THE EXPERIMENTAL ASST D-955 SUPERTENDANT UP TO HIS RETIREMENT IN THE EARLY 90,S I AM JOHN PERELLI HIRE DATE OCT 23RD 1967 FUEL CELLS SOUTH WINDSOR 1969 XFERRED TO D-955 EXP ASSY EAST HTFD WHERE I MET DENNIS GROUT AS A LABOR GRADE 5 I BEING A GRADE 7 I AM STILL EMPLOYED AS YOU CAN SEE BYE EMAIL ADDRESS I WENT OVER 55YRS ON OCT 23RD 2022 THE MUSUEM IS A VERY INTERESTING PLACE LOTS OF AIRCRAFT HISTORY OK ILL TURN IT OVER TO WHOM EVER JOHN PERELLI CLOCK # 212749 JOHNPERELLI@AOL.COM

Bob Melusky says

Bob Melusky says

January 14, 2023 at 3:39 pmInteresting to read about that low bridge story. I heard about that from my father.

The Capitol Ave building was demolished some years ago. A parking lot was built on the site using Busway money.

Here is a link to a photo of Jimmy Doolittle at the hangar standing in front of a Hamilton Standard propeller, a Wasp engine, and a Granville Brothers Gee Bee made in Springfield.

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=708982025801197&set=oa.193812110812684