Prudent and P.C.

Canterbury (Google Maps location)

June 2019

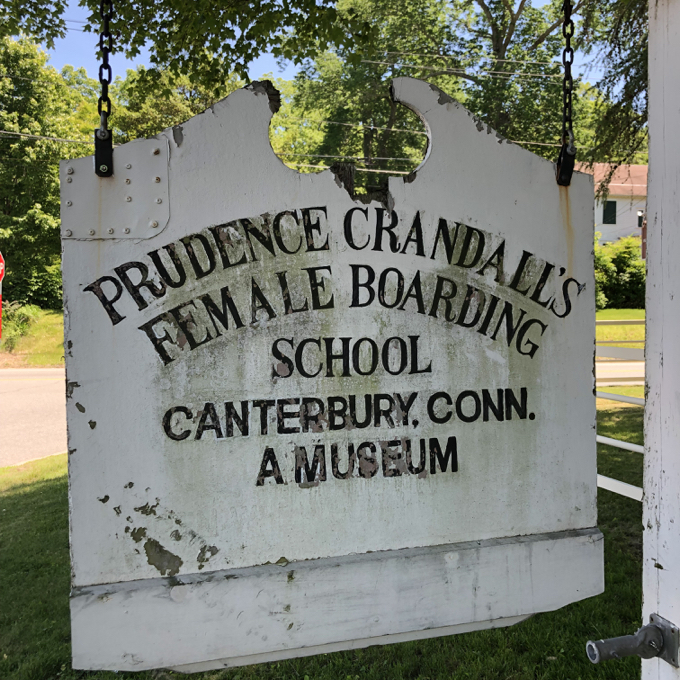

Yes, I’ve finally visited the Prudence Crandall Museum. On the face of it, it’s “just another” large Georgian historic House museum on a quiet back road in Connecticut. One of a hundred. Heck, travel routes 69 and 14 starting at the Prudence Crandall House, north, south, east, or west, and you’ll pass several others before you reach the end of whichever road you choose.

Such as it is in an old colonial state I suppose.

But here’s the thing: This place isn’t “just another” historic house. Prudence Crandall wasn’t “just another” historical Connecticut figure. Not at all. She’s not the official State Heroine for no reason.

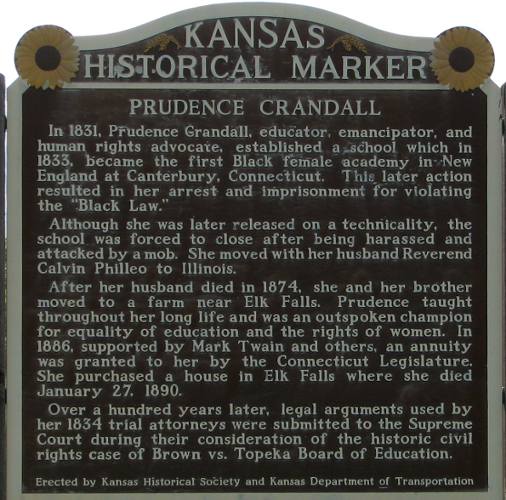

In fact, this page is but one of five on CTMQ regarding this house and/or woman. It’s a National Historic Landmark, and an important part of the Connecticut Freedom and Women’s Heritage Trails. She’s also part of the traveling Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. Heck, a Connecticut flag flies in the middle of Nowheresville, Kansas because Crandall lived out there before she died. The National Park Service equates Prudence Crandall and her story to the civil rights battlegrounds like Little Rock.

The Prudence Crandall Museum is certainly one of the most important sites in the whole state of Connecticut, period.

Hold on for a second though. I just went back to the Kansas thing and it’s lovely that they pay tribute to Crandall there, in Elk Falls.

But what’s up with Elk Falls, Kansas? It has two claims to fame: An annual Outhouse Tour and its billing as the World’s Largest Living Ghost town. About 120 people live there.

Our Dear Prudence deserves better. Like how about being part of the National Women’s History Museum, to be built in Washington DC? Yup, she’ll be there.

Moving on… I visited the museum on Connecticut’s annual Open House Day. As such, several tours were going on and I wasn’t alone in a historic house museum for once. In fact, the (small) parking lot was full and I had to find a spot across the street in a shopping plaza. Fantastic!

The museum is run by the state, but has a very local feel to it. Big city big wigs probably don’t get out to Canterbury too much to muck up a good thing. I chose to tour the house on my own, which is fine to do here if you like to read.

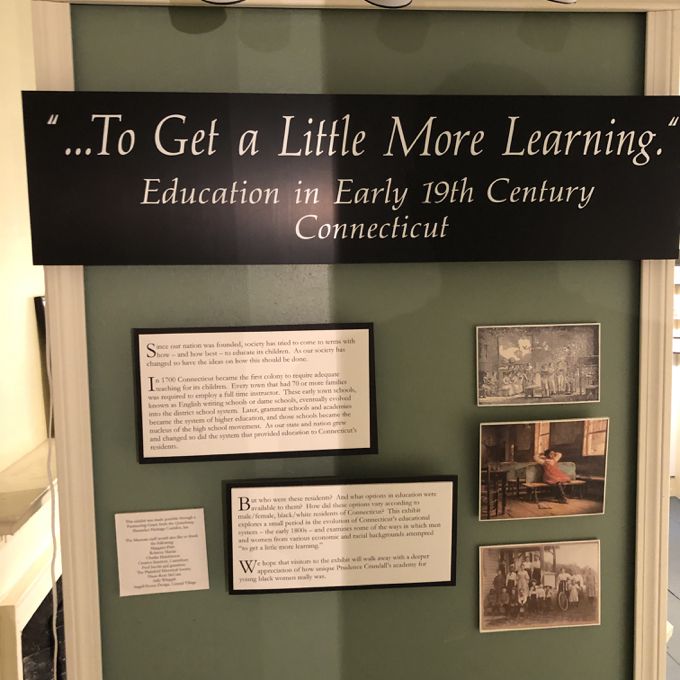

The Crandall Museum does suffer from that affliction of over explaining everything. There are hundreds of placards, signs, captions, etc. On the one hand, I get it and I appreciate it. On the other, I think it probably turns off a lot of people. Look, I’m the last person to throw stones about editing, but… I’m not an important museum either.

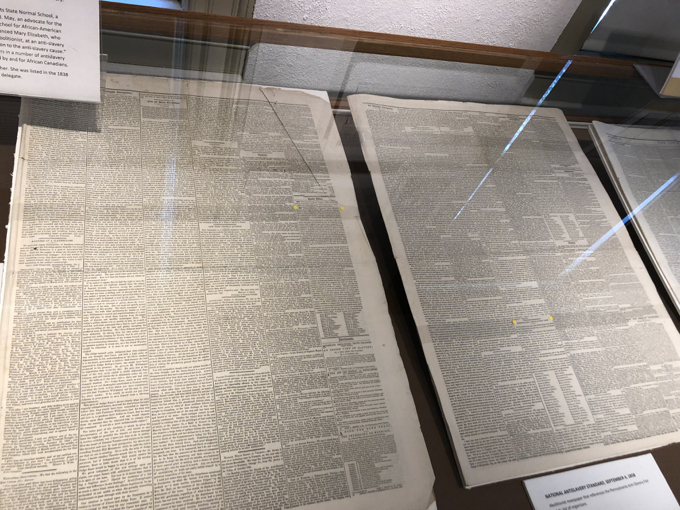

Speaking of wordiness, look at this 19th century newspaper. I just can’t imagine reading this! It’s bonkers!

Crandall was born in Rhode Island into a farmer family. They were Quakers and young Prudence received a high-quality education at the New England Friends’ Boarding School in Providence. She studied science, Latin, math… things that girls back then rarely got to learn about. Shout out to the Quakers for caring about girls’ educations back then.

Crandall grew up and got a teaching job in Plainfield, Connecticut when her family moved to Canterbury. In 1831, the town of Canterbury approached Crandall about establishing a school in their town. She agreed and purchased a house with her sister Almira Crandall, to establish the Canterbury Female Boarding School. The school was to educate the wealthy folks’ daughters around the area.

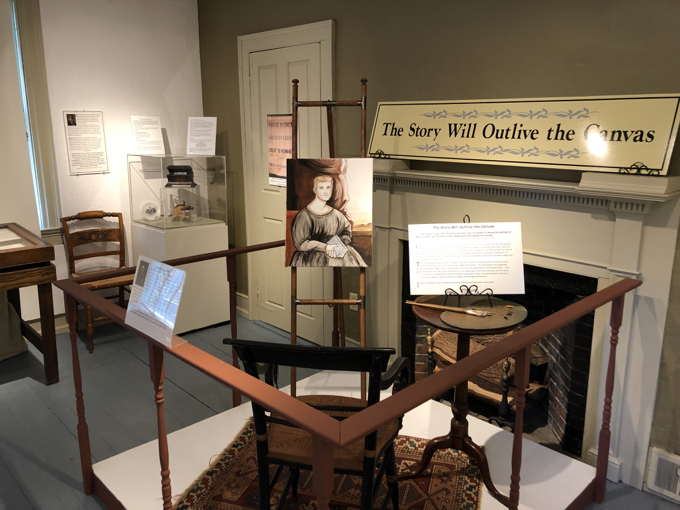

It was successful off the bat. Owing to her own background, she taught the subjects girls rarely experienced like chemistry, astronomy, history, etc. Painting and music and French were also available for an extra charge. The expensive $25 per quarter fee allowed Crandall to pay off her mortgage and everything was looking great for the young teacher.

Her school was ranked among the best in the region – and it was for girls! in 1831! This was pretty revolutionary stuff.

Dear Prudence

Then the craziest thing happened. In her second year of running the school, in 1832, Crandall admitted Sarah Harris, a black woman from a successful family, who sought to become a teacher. Harris was 20, and was the daughter of free farmers from Norwich. She was educated and well-respected… and was aware of the potential difficulties of her attending the school.

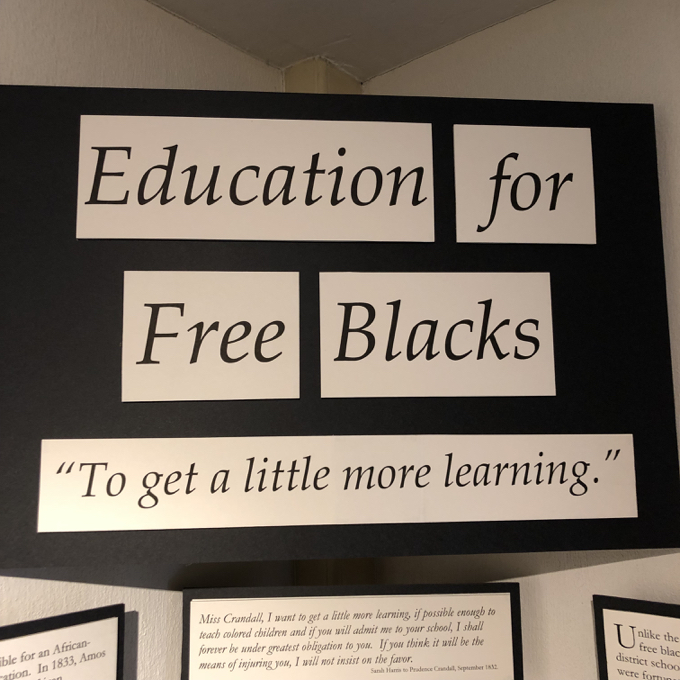

Harris famously wrote, “Miss Crandall, I want to get a little more learning, enough if possible to teach colored children, and if you will admit me into your school I shall forever be under the greatest obligation to you. If you think it will be the means of injuring you, I will not insist on the favor.”

Her attendance at the school makes the Canterbury Female Boarding School arguably the first integrated school in America. Although it wasn’t integrated for too long, as all the rich white people withdrew their daughters from the school – despite the fact that, as far as we know, none of the white students objected to Harris’s presence.

So, yeah, local white parents were outraged when Crandall refused to expel Harris. So what did Crandall do? Move? Quit? Open a separate school? No way, not our state heroine.

She transformed her school into one exclusively for black girls. Man, I love that. I really do. Of course, the local white people weren’t too keen on this, fearing a back invasion and – gasp! – interracial marriage. When one prominent local white guy brought up the marriage thing, Crandall responded, “Moses had a black wife.” She was the best.

The young nation’s leading antislavery newspaper, The Liberator, ran ads and articles helping Crandall attract young black women to her school, further fanning the flames of racism. On April 1, 1833, twenty black girls from Boston, Providence, New York, Philadelphia, and the surrounding areas in Connecticut arrived at Miss Crandall’s School for Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color.

White Canterbury townspeople continuously protested Crandall’s school. When the students ventured beyond the school, they were met with taunts, threats and violence. Some whites pelted them with eggs, stones or manure. (When my wife and her siblings came to America as refugees, they too were taunted verbally and with stones while walking to school. That was in the mid 1970’s. Just putting that out there.)

Crandall kept at it.

So the state of Connecticut passed something called “The Black Law” in 1833, making it illegal to run a school teaching African American students from a state other than Connecticut. As many of her students were from out of state, Crandall was arrested and thrown in jail. (For one night, but still.)

Under the Black Law, KKKanterbury residents refused any amenities to the students or Crandall, closing their shops and meeting houses to them. Stage drivers refused to provide them with transportation, and the town doctors refused to treat them. The even poisoned the school’s well with manure, and prevented Crandall from obtaining water from other sources. They also ostracized Crandall’s father. Through all of this Crandall continued to teach the girls which only angered the community even further. Have I said she was the best? She was the best.

The trial resulting from her arrest was a mess; first a hung jury, then a conviction, then an overturning by a higher court. Check this out. Andrew T. Judson, a Canterbury local, Connecticut judge and US representative, and all around [expletive], had this to say about Crandall, her school, and blacks:

We are not merely opposed to the establishment of that school in Canterbury; we mean there shall not be such a school set up anywhere in our State. The colored people never can rise from their menial condition in our country; they ought not to be permitted to rise here. They are an inferior race of beings, and never can or ought to be recognized as the equals of the whites. Africa is the place for them. I am in favor of the Colonization scheme. Let the niggers and their descendants be sent back to their fatherland and there improve themselves as much as they may, and civilize and Christianize the natives, if they can. …You are violating the Constitution of our Republic, which settled forever the status of the black men in this land. They belong to Africa. Let them be sent back there, or kept as they are here. The sooner you Abolitionists abandon your project the better for our country, for the niggers, and yourselves.

“Send them back.” Hm. I think I heard that same refrain in 2019. Sigh.

When Crandall’s conviction was overturned by a higher court, local idiots went bananas and an angry mob smashed up the school in late 1834. This was after trying to burn it down. Fearing for her students’ safety, Crandall finally closed the school and the students returned their homes.

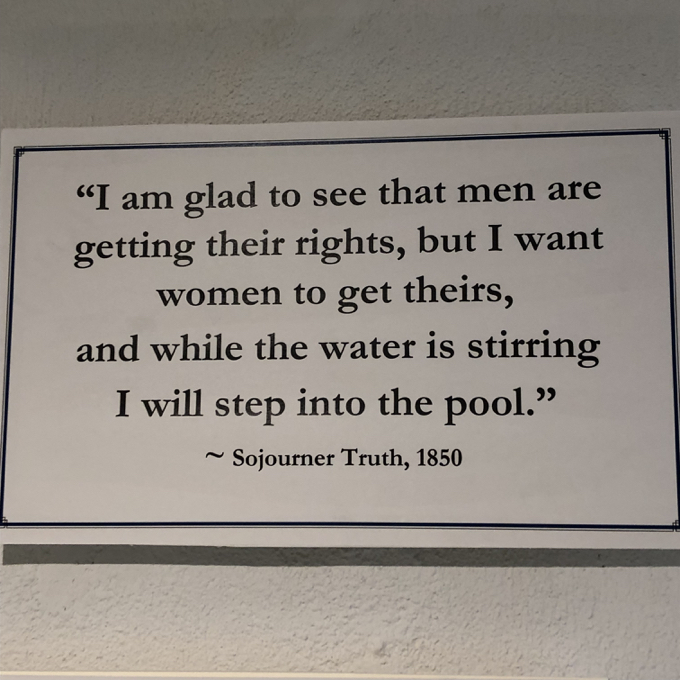

Crandall moved to Illinois and continued in the suffrage and abolitionist causes. She married a minister and was probably pleased when Connecticut repealed the Black Law in 1838. At the urging of Mark Twain and others, the state also granted her a pension in 1886 but she never returned here. And that’s when she wound up in Nowheresville, Kansas and died.

Another interesting Kansas connection – Crandall’s trial in Connecticut was cited in the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education (Topeka, KS) as a precursor set of statutes.

In 1996 Connecticut named her the official state heroine. And in 2019, I visited and wrote about the museum. This is an important place; an old pre-Civil War school that we white people should visit to face America’s past head on. This crap is still going on today, all of the US and world. Our schools in Connecticut are still segregated in different, sneakier ways.

I hate to sound so pessimistic, but I don’t think we’ll ever reach true equality – at least not before we all die in the Climate Catastrophe Mad Max societal collapse anyway.

![]()

Lots of the info above is from Wikipedia, cross-referenced from too many sites to mention.

Prudence Crandall Museum

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Cheryl Camacho says

Cheryl Camacho says

September 25, 2019 at 1:38 pmGreat information – Thank you for sharing.

I don’t live not far from this museum, have been by it millions of times in the past 30 years.

Always wanted to stop . . .

It’s on my calendar to visit this weekend!

Jan says

Jan says

May 25, 2024 at 1:19 pmI am writing something for my 3rd graders about Prudence Crandall. May I use your images in my article? I live in Connecticut and could go and take my own photos, but yours are so good! Thank you.