A Full Slater of Art

Norwich (Google Maps Location)

November 14, 2008

This place absolutely deserves a proper revisit, as they’ve updated the joint pretty significantly – and because this page doesn’t capture the greatness of the Slater.

The Slater Memorial Art Museum is a Connecticut Art Trail site

Ahhh, my first Connecticut Art Trail art museum! Oh sure, I’ve been to a few university galleries and museums among my first 79 museums for this site, but not a large important art museum like the Slater. For you lazy types that never read more than the first paragraphs on this blog? The Slater Memorial Art Museum is really, really unique and cool.

Consider this: The Slater Art Museum contains one of the three largest collection of Greek, Roman and Renaissance sculpture casts in the country. Also, and this is important, it is one of only two fine arts museums in the United States on the campus of a secondary school.

The Slater was the centerpiece of my full day out and about in this part of the state. Earlier I’d seen Hell Hollow, Cottrell Brewery and a bunch of other smaller stuff in Norwich – and had spoken at the New England Museum Association Conference as well, but this was where I knew most of my CTMQ energy would be focused.

In fact, in the post-talk meet-n-greet session, I told a few people where I was headed and one woman seemed thrilled I’d be hitting the Slater. She cheekily said, “I’ll be very interested to read what you think about it.” I believe she does read this blog so here you are.

This is a crazy museum. Art snobs probably hate it, but art know-nothings like me probably usually dig it. Why? First of all, it covers a massive gamut of styles, periods and cultures. And the complete quirkiness of the collection certainly make it interesting.

The Slater is located on the campus of Norwich Free Academy – an odd school in its own right. The NFA offers over 2,500 students a unique combination of the best in private and public education. NFA serves as a secondary school of choice to Norwich and seven surrounding communities that are tiny and rural (Bozrah, Canterbury, Franklin, Lisbon, Preston, Sprague, and Voluntown), as well as tuition students. The Academy is a privately endowed, independent, comprehensive high school that educates students in grades 9-12. Hm. So a public school for lucky local kids and private school for rich random kids.

But let’s get back to the museum. Dedicated in 1888 and housed in a stunning Romanesque Revival building, the Slater’s local collection represents 300 years of Norwich history. Included are 18th – 20th century American paintings and decorative arts, including contemporary Connecticut crafts, 17th – 19th century European paintings and decorative arts, African and Oceanic sculpture, Native American objects, and a plaster cast collection of Egyptian, Archaic, Greek, Roman and Renaissance sculpture. The adjacent Converse Art Gallery hosts six changing exhibitions throughout the year.

The Converse Gallery

For more than one hundred years, the Museum has displayed and interpreted the best examples of fine and decorative art, representing a broad range of world cultures of the Americas, Asia, Europe, and Africa. So you see, one minute you’re admiring a 150 year old painting of Norwich’s Yantic Falls and the next you’re standing next to a cast of a 3,000 year old Greek statue. Awesome.

Instead of me trying to explain what the Slater is all about, I’ll let them do it. Please note that the following is excerpted from an article titled, “What is This Place?” Which is not usually a normal question at art museums. But this isn’t a normal art museum.

In 1886 William Albert Slater, the son of a wealthy Norwich industrialist, offered to memorialize his father, John Fox Slater, with a new building at the Norwich Free Academy. He chose noted Worcester, Massachusetts architect, Stephen C. Earle, to create a distinctive design. To many, the Slater Memorial was, and remains, Earle’s finest work. Its design is Romanesque Revival in what has become known as the Richardsonian Romanesque after another noted 19th century American architect, Henry Hobson Richardson.

Scion of the same Slater family noted for industry in Rhode Island, William A. Slater was educated and successful. He appreciated travel, theater, music and art and during frequent visits to France with his wife Ellen, purchased contemporary art. He sponsored the construction of Norwich’s “Broadway Theater” and numerous performances in it. At the same time, his philanthropy provided for the expansion of educational opportunities and affordable access to the arts for Norwich’s citizens. His generosity touched every resident of the city in someway.

By 1888, recently appointed Norwich Free Academy Principal Robert Porter Keep convinced Slater to add to his gift of the building, funding adequate to acquire 227 plaster casts of classical and renaissance sculpture. Keep was a noted classics scholar who had lived in Greece. Almost 600 photographs of the great works of European and ancient art and architecture were then added to the plan to create a museum that would serve the students of the Norwich Free Academy and the community by exposing them to cultures and aesthetics otherwise outside their reach. The approach was one not uncommon for major museums in 19th century Western academic institutions, but unheard of in a small American city on the campus of a secondary school.

Dr. Keep appointed Henry Watson Kent to be the museum’s first curator and engaged Edward Robinson, curator of antiquities at the Boston Museum of Fines Arts to select the casts and plasterer Giovanni Lugini to assemble the plaster parts into replicas of the great masterworks. To anyone else, the dismembered parts would have posed a puzzle of insurmountable proportions, but Lugini clearly assembled them accurately. He was also charged with fitting the casts with fig leaves their arrival, a practice employed in England as well.

Kent was the perfect choice to lead the museum, and utilized methods still seen as valid today to engage the public in repeated visits. He organized changing exhibits and took advantage of the availability of private collections such as William and Ellen Slater’s when mounting temporary exhibits. The Slaters’ collection drew 3,000 visitors. The museum continued to collect, often purchasing from living artists as the result of temporary exhibitions and accepting gifts from generous Norwich citizens and Norwich Free Academy alumni. Thus, the museum’s holding’s grew to include a diverse array of fine and decorative art, historical artifacts and ethnographic material from five continents and 35 centuries.

Over the course of more than a century, the museum has remained true to its mission as an educational resource for the Academy and the community. Successors to Mr. Kent continued to enlarge and improve the collections through purchases and donations. Its space was expanded in 1906 through a gift from Charles A. Converse for the addition of a new building with a large, airy gallery, making changing exhibits more feasible. The Slater Memorial Museum’s relationship with the Norwich Art School has, over the years, maximized the Norwich Free Academy’s ability to train young artists for professional study, while contributing to the cultural life of the greater community.

Phew, that was a lot of historical info. But hey, I’ve got a lot of pictures from this place so I need enough verbiage to show them throughout the story. And by the way, the Slater is pretty darn dark and I didn’t want to draw attention with flash photography, hence the darkness of the pictures.

There is really no set way to view the museum; you just browse at your whim. I walked (alone) through the large hall (called The Cast Gallery) to the back first and checked out the Regional American Paintings Collection. The Slater Museum’s collection includes dozens of paintings that reflect the superior artistic skill and craftsmanship of regional artists. The artwork captures early life in Norwich and Southeastern Connecticut through the depiction of people, landscape, and the built environment. Currently on view are several landscapes by 19th Century Norwich painter, John Denison Crocker.

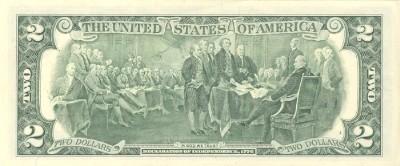

I liked Crocker’s work. He was a member of the “Hudson School” of American painters that hung out in the Adirondacks for inspiration. There were also paintings by John Trumbull. If you’ve never heard of him, you should have. He had quite the life. In fact, I can guarantee you have seen – on more than one occasion – a Trumbull painting. If you’ve ever seen a two dollar bill you have! For he painted the Declaration of Independence scene on the back of it.

Painting by a Connecticut native. It’s only worth two bucks though.

As if that’s not cool enough, there’s a museum at his birthplace up in Lebanon. He’s buried underneath the Yale University Art GAllery. He served as an aid to George Washington during the Revolutionary War. His dad was Governor of Connecticut. He had only one eye. He witnessed the battle of Bunker Hill.

Oh yeah, and he painted really cool wartime paintings. Other artists featured in this very nice exhibit are Alexander Hamilton Emmons, Ozias Dodge, and Daniel Wadsworth Coit.

The whole exhibit is new to the Slater and is permanent. It’s called “Crocker’s Norwich: The Long Nineteenth Century,” and it ties together art and industry in Norwich during what many view as its most successful era. There’s so much more to discuss about this exhibit, but you can Google for it – or better yet, visit the Slater yourself.

I decided to keep the Cast Gallery for last and instead made my way up the stairs to the second floor. This is where the Slater really sets itself apart from other art museums. There are just as much history and artifacts as there is art. I’m going to sort of rip through these various exhibits, but please understand that they are neither lacking or boring.

Up first, the “Nautical Display.” I like nautical stuff. My notes from my visit state, “boats.” Gee, thanks, me. Fortunately the brochure says there are “Ship logs, models, paintings, and scrimshaw articulate Norwich’s heritage as an important commercial trade and seafaring center.”

Over in the “Raymond B. Case Gallery” there are things like “Textiles and furniture presenting three centuries of life and style.” My notes state “jugs.” My notes are awesome.

There is an “American Room” and a “Nineteenth-Century Gallery” which contain things like silverware, guns and armaments, clocks and a Whittlesey piano. The clocks are by Thomas Jackson, John Avery and Thomas Harland – apparently all important Norwich clockmakers. The piano is the work of the country’s first piano maker and founders of the first American music seminary.

My notes? “Guns.”

So that’s the American history stuff, but there’s oh-so much more here. Like the Anglo-American Galleries, the Renaissance Wing, the Paul W. Zimmerman Collection of African and Oceanic Art. But wait there’s more! The Pre-Columbian & American Indian Wing, the Oriental Collection and the Vanderpool Collection of Oriental Art. Phew. Let’s turn to the Slater website for some info…

The Museum’s small but significant collection of African art was greatly enhanced in 1998 with the donation of an extensive collection of African and Oceanic art. The donor was Paul Zimmerman, Professor Emeritus of the Hartford Art School. The collection includes African masks, sculpture, and utilitarian items from the Ivory Coast, Mali, Ghana, Zaire, and Liberia and Oceanic artifacts, including spirit boards, carvings, and sculpture.

And…

Among the objects on display in the Museum’s collection are example of six Native American cultures, namely the Chiriqui of Panama, prehistoric; the Chimu of Peru, prehistoric; the Mound Builders of the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys, prehistoric; the Pueblos, who have inhabited the southwestern part of the United States since about 1200 A.D.; and the Northwest tribes, including the Inuits. Navaho rugs, woven baskets, and utilitarian artifacts are among the items on exhibit. Additionally, there are displays of arrowheads from the local region, as well as other stone implements from Native Americans of Connecticut.

What doesn’t this place have?! I’ll tell you more of what it does have…

The Vanderpoel Collection of Oriental Art, which was presented to the Slater Museum in 1935, has been augmented over the years by private donations and Friends of the Museum acquisitions. The original collection consists of artifacts and textiles that are primarily from the Tokugawa period of Japanese art (17th – 19th centuries A.D.) and includes temple carvings, woodblock prints, stencils, metal work, pottery, and sculpture. Examples of Chinese and Korean artworks from various periods are also represented. The collection has been enriched over the years with the addition of carved ivories, Samurai armor, and fine examples of Chinese export ware and Buddhist sculpture.

Those are shoes. C’mon now.

Wow. And you thought I was exaggerating when I said this museum was eclectic! One note I wrote in one of the Asian rooms was “Samisen – Japanese strings.” This is the name of that horrible twangy instrument that we Americans like to mock.

Samisen

On may way back through the previously seen exhibits, I noticed a long case containing a ton of thimbles and spoon. That’s it, just old thimbles and spoons. These lie under the watchful eye of a few giant old Greek (or Roman, I don’t know) statues.

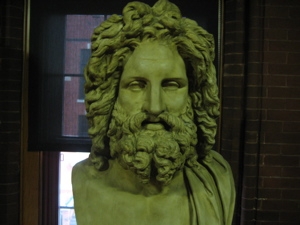

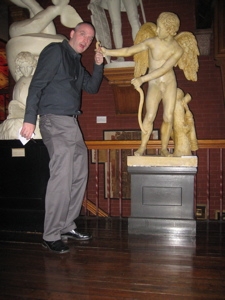

So, about all those statues – the things that really make the Slater Art Museum truly different, at least here in Connecticut. They line the corners of the second floor and many of them are massive. The ones with heads peer down at visitors from all angles.

In addition to those spread about the upper floor, there is an entire large gallery of them below. But why? What are these things and are they real? The answer is a somewhat complicated “sorta.”

Back in the 1880’s, the museum’s namesake and the good Dr. Keep previously mentioned teamed up and decided to house a collection of Greek, Roman and Renaissance casts for the museum.

On March 23, 1887 Edward Robinson, then in charge of the classical collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, accepted the appointment to select, purchase, and install in the museum a collection of casts from renowned works of antiquity. The selection of casts was made with extreme care; only the finest works available were chosen. Plaster replicas were viewed by the connoisseur with the same relevance and solemnity that the original works would have evoked. Moreover, in the 19th Century, America witnessed the burgeoning of museums and libraries which fostered the belief in classical education. A hundred years later, the Slater cast collection, one of the three largest in the country, is considered by many to be the best of its kind.

Wow. It’s just crazy. Apparently these guys commissioned casts of anything and everything deemed important. The Slater website has great descriptions (and infinitely better pictures) of many of the casts. I won’t even begin to describe them, but I’ll offer a smattering of what you can see there.

Collections are divided among Egyption, Assyrian, Cypriote, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic and Renaissance. Some of these things are HUGE; entire building facades from Greek buildings or huge bas relief tablets from Cypriot. I’m telling you, even though they are “just” casts, you have to see this place to believe it. I apologize for not properly matching my lame pictures up with what they are, but really… does it matter?

Some examples are:

Amenhotep III, The Magnificent: Cast of the original in the British Museum, London – Egyptian Dynasty XVIII (c. 1570 – 1320 B.C.)

Perseus Slaying Medusa: Cast of the original in the Museum at Palermo – Greek – late 7th century B.C.

20. Archaic Head of a Man: Cast of the original in the Staatliche Museum, Berlin – Greek – 6th century B.C.

21. Head of Athena: Cast of the original in the Berlin Museum – Greek – 6th century B.C.

The Diskobolos or Discus-Thrower: Cast of the original in the Vatican, Rome – Roman copy of Greek original – 5th century B.C.

Figures from the Eastern Pediment of the Parthenon or Temple of Athena Parthenos: Cast of the original in the British Museum, London – Greek – 5th century B.C.

Silenos and the Infant Dionysos: Cast of the original in the Louvre, Paris – 4th Century B.C.

David: Cast of the original in the Museo Nazionale, Florence – 15th century

King Arthur: Cast of the original in the Foundation Church at Innsbruck, Austria – 16th century

There are about 150 casts in all. I figure you have two options; you can travel around the world and spend $10,000 to see the originals (mostly in NYC, London, Greece, Italy, Paris, and Germany) or drive down to Norwich, donate a few bucks, and experience them all at once. Your choice.

Each cast is explained in detail at the museum (and on the website). It really is rather stunning and I haven’t done it justice here at all. Just when you thought I was done… there’s another wing to this place!

The Sears Gallery. What could this possibly contain? Why, the Slater Museum’s collections of English and European paintings and decorative arts from the 15th through the 20th centuries, that’s what. This gallery contains paintings and decorative arts from primarily England, France, Italy, and Spain. And just for the heck of it, it also has examples of English and European furniture.

My mind sufficiently blown, I was through the museum. I can’t imagine there’s another museum where one can admire 300 year old Chinese scrolls while Donatello’s David looks on next to a collection of old Norwich clocks.

I told you, I loved this place.

![]()

Laurie says

Laurie says

April 10, 2009 at 11:20 amI’m an alum of NFA, a NEMA conference attendee, a ctmuseumquest reader, and a CT museum employee – glad you liked Slater! I took art classes at NFA from elementary school on, and through high school. You should head back in the spring – when they do the Student exhibition in the Converse gallery. Good stuff. Unique place. P.S. There’s 2 good pubs in downtown Norwich to grab a pint – Chacer’s and Harp & Dragon.

Dan Moore says

Dan Moore says

October 10, 2009 at 3:47 pmSlater is a jewel that is overlooked by many interested in Conn….especially eastern conn art,architecture and generally the material culture of eastern conn from the late 17th cent through the victorian era.The collection of Emmons paintings needs to be highlited from time to time and not buried in the lecture hall and the collection of the whole museum DESPERATELY needs to be catalogued.This place is a great source of information to collectors and amatuer historians like me and it has been an inspiration and a guide as to what and how I collect for many years.

Reggie says

Reggie says

January 29, 2011 at 1:10 amI’m graduated from NFA in recent year, and I was very excited to come across this article. Slater is a great place, and I feel honored to have had access to the museum as a student. As an art student now, I’ve come to see what a privilege it is to have a place like this at my disposal in my hometown. Sadly it really is an overlooked gem in the area. Many students never use the facility and people from Norwich rarely give it a second thought. The faculty there is dedicated and AMAZING. The museum and it’s employees are a big part of the reason I pursue art today. It’s great to see someone who really sees Slater for what it’s worth. Thank you!

Henry S says

Henry S says

March 7, 2025 at 8:22 pmI had a great time visiting. They really have a lot of unique stuff. I go to a lot of museums, and they definitely aren’t trying to mimic other collections, which is wonderful. Norwich has a lot of interesting architecture, so I’d consider Norwich to be an underappreciated gem in CT.