Gettin’ Nasty

West Hartford (Google Maps Location)

March 11, 2009

Update: This is now the “Art Gallery at the University of St. Joseph” as the school stepped it up a bit in 2012. Also, it is now part of the Connecticut Art Trail. I really should revisit this place and get better pictures, as it’s only a few minutes from my house. But… nah. These terribly formatted older pages on CTMQ have their charms.

This art gallery is a Connecticut Art Trail site

I keep getting scared that my list of 500-plus museums in Connecticut is still short of the true total. Why? Because I keep finding little museums within a couple miles of my own house that I didn’t know about. How many others are hidden around the state?

2019 Narrator: A lot.

Once I found that most colleges have art galleries and once I decided that they were worthy of a CTMQ visit, I found a bunch more around the state. One such college art gallery is at St. Joseph College, which Damian and I pass every day on the way to his preschool. It’s right across the street from the UConn branch at West Hartford. St. Joseph is a college for women only but has a gym and pool for local people like me – that’s right I could join a gym and pool that services mostly college aged women.

Pardon me while I think about that for a moment…

2019 Narrator: Hoo-boy. As I said, the former college is now a university but beyond that, SJU is now open to men and the UConn West Hartford branch is now closed (moved to Hartford). And Damian is 13.

Hm. Okay, let’s talk about art.

The Saint Joseph College Art Gallery in the Bruyette Athenaeum houses the College’s distinguished collection of fine art. The nucleus of this collection was donated to the College on the occasion of its fifth anniversary, in 1937, by the Reverend Andrew J. Kelly, and was augmented by a major bequest from the Reverend John J. Kelley in 1966. Since then, the collection has grown to over 1,700 objects with particular strength in American paintings of the early 20th century, including works by Thomas Hart Benton, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Milton Avery, and European and American prints from the 15th century to the present, including works by Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, George Bellows, and Childe Hassam.

Aside from the small permanent collection on display, there is a slightly larger exhibition space for temporary shows. During our visit, this was “Good as Gold: Nineteenth-Century Financial Controversies Through the Eyes of Thomas Nast.” Renowned political cartoonist Thomas Nast weighed in on a range of financial issues that faced late nineteenth-century American society. His trenchant visual commentaries in the pages of Harper’s Weekly helped shape opinion in an age that faced many issues similar to those of today. Monetary policy, taxation, inflation, and tensions between trade unions and business owners were among Nast’s most frequent topics in the 1870s, when he was at the height of his powers.

Nast’s arsenal consisted of his extraordinary skill as a draughtsman combined with a clever and biting use of puns and symbols both borrowed and invented. The Bible, Shakespeare, and Aesop’s Fables provided inspiration, as did popular songs and current colloquial expressions. In the course of his career at Harper’s Weekly, Nast codified the use of the Elephant and the Donkey to represent the Republican and Democratic Parties and employed the traditional personifications of the United States, Lady Liberty and Uncle Sam, to bold effect in witty and powerfully persuasive images.

I was (and this is true) actually interested in the exhibit and after about five minutes realized it would have been better to view it sans three-year-old. Let’s face it, Nast is a bit highbrow for the toddler set. Give Damian some Rothko, Lewitt or Motherwell – not 150 years old political symbolism and satire. Oh well… One can never start an appreciation for such too early. Right?

The gallery is the typical sterile affair, but I like that. I go to art galleries for the art, nothing more. The space is divided into several small rooms; which I’m sure presents some challenges for other exhibits. It was, however, rather perfect for Nast.

Nast drew for Harper’s Weekly from 1859 to 1860 and from 1862 until 1886. In February 1860 he went to England for the New York Illustrated News to depict one of the major sporting events of the era, the prize fight between the American John C. Heenan and the English Thomas Sayers. A few months later, as artist for The Illustrated London News, he joined Garibaldi in Italy. Nast’s cartoons and articles about the Garibaldi military campaign to unify Italy captured the popular imagination in the U.S. In 1861, he married Sarah Edwards, whom he had met two years earlier.

His first serious works in caricature was the cartoon “Peace,” (made in 1862) directed against those in the North who opposed the prosecution of the American Civil War. This and his other cartoons during the Civil War and Reconstruction days were published in Harper’s Weekly. He was known for drawing battlefields in border and southern states. These attracted great attention, and Nast was called by President Abraham Lincoln “our best recruiting sergeant”. Later, Nast strongly opposed President Andrew Johnson and his Reconstruction policy.

Nast’s drawings were instrumental in the downfall of Boss Tweed, who so feared Nast’s campaign that an emissary was sent to offer Thomas Nast a large bribe, which was represented as a gift from a group of wealthy benefactors to enable Nast to study art in Europe. Feigning interest, Nast bid the initial offer of $100,000 dollars up to $500,000 before declaring, “I don’t think I’ll do it”. Nast pressed his attack, and Tweed was arrested in 1873 and convicted of fraud. When Tweed attempted to escape justice in December 1875 by fleeing to Cuba and from there to Spain, officials in Vigo, Spain were able to identify the fugitive by using one of Nast’s cartoons.

Nast believed that the well-organized Irish immigrant communities in New York had provided the basis for Tweed’s popular support. Because of this, “along with Nast’s Anti-Catholic and Nativist beliefs,” Nast often portrayed the Irish immigrant community, and Catholic Church leaders, with extreme prejudice. In 1875, one of his works, titled “The American River Ganges”, Nast famously portrayed Catholic bishops as crocodiles waiting to attack American families. Nast’s anti-Irish sentiment is apparent in his characteristic depiction of the Irish as violent drunks, often with ape-like features.

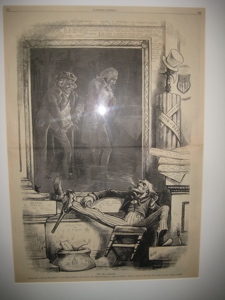

In general, his political cartoons supported American Indians, Chinese Americans and advocated abolition of slavery. Nast also dealt with segregation and the violence of the Ku Klux Klan, which was detailed in one of his more famous cartoons called “Worse than Slavery”, which showed a despondent black family having their house destroyed by arson, and two members of the Ku Klux Klan and White League are shaking hands in their mutually destructive work against black Americans. His cartoons frequently had numerous sidebars and panels with intricate subplots to the main cartoon. A Sunday feature could provide hours of entertainment and highlight social causes. His signature “Tammany Tiger” has been emulated by many cartoonists over the years, and he introduced into American cartoons the practice of modernizing scenes from Shakespeare for a political purpose.

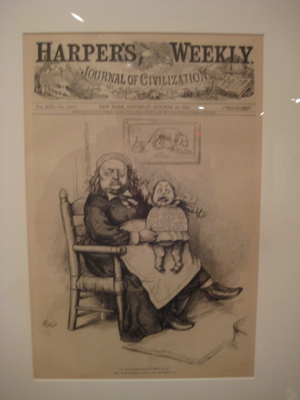

There’s much more to Thomas Nast’s work, but you can read that stuff via the links below. I dig well done political cartoons, and Nast was pretty much the progenitor of the art. As just one (of hundreds) example, the picture to the left depicts some politician named Benjamin Butler.

Butler’s ilk is certainly alive and well today in Connecticut. He apparently switched political parties in order to remain an elected official. Joe Lieberman anyone? This cartoon has all sorts of symbolism that I won’t burden you with, but I particularly like the picture of Butler’s dog hanging on the wall – the can stuck on his tail is (of course) the Republican Party driving him nuts while he sniffs a pile of excrement – which is apparently the Democratic Party in fecal form.

The exhibit was excellently presented and each work had a nice description to aide the visitor. And (for once), the descriptions made sense and were interesting… Something not always the case at art museums.

I didn’t spend too much time in the permanent collection area, as Damian had had his fill and quite frankly, I wasn’t sure the volunteer manning the door would have been too keen on my snapping photos. The Georgia O’Keefe paintings were quite small and certainly not her famous work.

Damian had to get back outside and back to splashing in the puddles. If only there were a puddle museum for him.

Damian back home in his happy place

My college gallery resume is still fairly weak, but I’m pretty certain that St. Joseph’s is one of the best. I’ll definitely be re-visiting – alone – especially during the receptions what with all the free food and drink and the whole 2 miles away thing.

2019 Narrator: Psst. Dude. Yale.

![]()

Leave a Reply