Tick, Tock, Tick, Tock… The Countdown to 100 Museums!

Bristol (Google Maps Location)

April 17, 2009

Amazing.

What I should write is, “Go to the American Clock and Watch Museum yourselves – even if you don’t give a hoot about clocks or watches. I can’t do it justice.” Unfortunately, by virtue of being CTMQ’s sole writer, I must attempt to write about my visit to the museum. But know this right off the top: I can’t possibly hope to begin to describe the complexity and completeness of the collection here.

I sped out to Bristol one day with the modest goal of simply going to my 99th museum. The reason being that I was scheduled to meet up with my sister and her family in a couple days down at the Norwalk Maritime Aquarium for what would be a “celebration” of my 100th museum.

Of course, no one knew that but me – but really, isn’t the 100th museum more fun with 5 little kids in tow? Plus, we had cake.

But that was still a few days away and I had a completely different museum to check out. Hm… Bristol… Old clocks and watches… This one would be quick and easy. Right? Boy, was I wrong.

Upon entering, I immediately realized the depth of my ignorance. There are a TON of clocks here. About 1500 to be exact! My word… Time’s a tickin’ – let’s get on with the museum. (As always with well established large museums, I’ll be borrowing heavily from their website for background and details.)

On October 24, 1952 Edward Ingraham, president of E. Ingraham & Company, invited ten local businessmen to the “Town Club” (now the DuPont Funeral Home) in Bristol to discuss forming a clock museum. Since Bristol had become an industrial town due to its designation as the world’s center of clock manufacturing, it seemed appropriate that a museum be formed to preserve the heritage of the industry for future generations. Although there had been discussion about renovating a home close to the factory on North Main Street or constructing a modern facility located on nearby Rte. 6, the 1801 home of Miles Lewis located on Federal Hill was purchased and renovated for the museum. Except for the modification of the stairway for safety and the conversion of the carriage shed into an apartment for the caretaker, the original features of the Federal style house were retained.

The Bristol Clock Museum opened its doors to the general public on April 10, 1954. At the time of the opening there were approximately 300 clocks on display and a small library containing 50 books. The collection grew quickly and by 1956 a new wing was added to the museum. Named the Ebenezer Barnes Memorial Wing, the addition was financed through the generosity of Fuller F. Barnes in honor of his ancestor, Ebenezer Barnes. The memorial wing was constructed using paneling from the homestead of Ebenezer Barnes, which is believed to be the first permanent residence erected in Bristol. The massive support beams used in this wing were once part of the Lewis Lock Company that was located in nearby Terryville. In 1958, due to the enlarged scope of the collection and the growth of membership, the name of the museum was changed to the American Clock & Watch Museum, Inc.

Continued growth over the next thirty years made it necessary to expand the facility once again and resulted in the construction of the Ingraham Memorial Wing in 1987. The additional 3000 square foot expansion improved display capabilities and provided a gallery area for the museum’s gateway exhibit, “Connecticut Clockmaking and the Industrial Revolution.” Future expansion plans include the incorporation of adjacent museum properties in order to offer additional display and research facilities as well as larger spaces for public programming.

Visitors to the museum will find over 1,500 clocks and watches on display including old advertising clocks, punch clocks, grandfather clocks, blinking-eye clocks, railroad clocks and even Hickory Dickory Dock clocks. While the museum is known to house the finest collection of American-made clocks on public display, its primary emphasis continues to be that of the Connecticut manufactured clock.

Fortunately, I was handed a nice little map and guide with which to aid my self-guided tour. Incidentally, I learned a new word here – horology – the study of the measurement of time. Clocks, watches, clockwork, sundials, hourglasses, clepsydras, timers, time recorders, marine chronometers, and atomic clocks are all examples of instruments used to measure time. In current usage, horology refers mainly to the study of mechanical time-keeping devices, while chronometry more broadly includes electronic devices that have largely supplanted mechanical clocks for the best accuracy and precision in time-keeping. Now we all know.

After paying and talking for a moment with the kind lady working there, I declined the optional “cell phone tour” and made my way through the gift shop area into the Barnes Wing. It must be noted that every single nook and cranny of the building displays an old clock or sign noting some sort of clock history.

One could spend at least a couple hours here – an hour more than I had allotted for my visit. There is a ton of information at every turn; posted in every dark corner and around every turn – I say this with affection rather than disappointment!

The Barnes Wing is a beautiful room. It contains the oldest and “most important artifacts in the museum.” It also has a large wooden sign noting the rather obvious: CLOCKS. Um… Yeah, I know. Lots and lots of ’em.

The collection at the American Clock & Watch Museum, Inc. includes clocks dating from 1680 and watches dating from 1595. With the exception of some items that date to modern times, the majority of the collection dates from 1800 to 1940. Mainly comprised of American-made timekeepers, the displays give particular prominence to those clocks that were mass-produced in Connecticut, as this state once held the distinction as the world’s great clock manufacturing area of the 19th century.

The clocks here are displayed pretty much in the order of creation and each one is accompanied by a very informative description or story about the local clockmaker who made it. As if this place was created for nerds like me, the museum denotes such important facts as “the tallest clock” and “the oldest clock.”

The tallest clock here

Oh? You want to know what they are? The tallest clock stands at nine feet, ten inches and was made in 1885 with a mixture of a Swiss 30-day movement and a New York casing. Another random clock fact: A “prayer strike,” which this clock has, not only strikes to hour to remind one to pray, but strikes again 90 seconds later to remind you to stop.

And the oldest? That’s an English Lantern clock from 1680. It uses the ol’ “rack and snail” striking method which was invented in 1676. This system automatically adjusts a clock’s striking to the correct hour if the hands are moving forward too rapidly.

The oldest clock here

There are a bunch of cool and interesting clocks in this one room – and we have much more to see yet. One particular display has all the parts of a clock separated and glued onto a board which really gives quite an impression at just how complicated these things were.

Many of the clocks in the room still chime and spending time in there sometimes felt like I was “inside” that Pink Floyd song, “Time.” Along the far wall were a bunch of watches and alarm clocks from antiquity, but also a large display of watch keys.

There are many famous names from Connecticut’s clock-making past. Eli Terry – whose name is memorialized today by Terryville right down the road from the museum – and Seth Thomas – from which Thomaston got its name. More on Terry later, as for now we’ll stick with a little Seth Thomas history.

The Seth Thomas Clock Company was organized as a joint stock corporation on May 3, 1853 to succeed the earlier clockmaking operation of the founder. Seth Thomas (1785-1859) had been manufacturing clocks at the site since 1814.

After Thomas’s death in 1859, his son Aaron became President and began to add new clocks to a conservative line. About 1862, the firm purchased the patent rights of Wait T. Huntington and Harvey Platts of Ithaca, New York and added a perpetual calendar clock to their line. They also added a line of “Grandfather” clocks in the 1880’s

The Seth Thomas Clock Company was very prosperous into the 20th century and was considered the “Tiffany’s” of Connecticut clock manufacture, even by their competitors. Between 1865 and 1879 they operated a subsidiary firm known as Seth Thomas’ Sons & Company that manufactured a higher-grade 15-day mantel clock movement and during that period were major supporters of a New York sales outlet known as the American Clock Company. After 1872 they also became a major manufacturer of tower and street clocks. Between 1884 and 1915 they were manufacturers of jeweled pocket watches.

Some of us who care about this stuff still get a thrill from seeing original Seth Thomas clocks on churches or street clocks around the state. The company’s legacy still stands tall today.

Moving on, across the room, there are a bunch of watches here too.

Before digital watches, before that little dial to wind on the side of them, watches had to be hand wound with a key. The museum displays all sorts of different watch keys, many of which contain precious gems and are made of precious metals. I’m sure that high society used to nonchalantly flaunt their expensive watch keys as a matter of status. Pompous hypothetical jerks that they were.

Before leaving the room (again, if you’re really into clocks, you could easily spend a good 45 minutes in here alone), I noticed an interesting marble clock high up on the wall. It was purchased in 1900 by a tobacco leaf growing company in Hartford and takes three or four men to mount it firmly on a wall. The weighted pendulum inside it cannot be accessed at all to restart it, but rather a “flipper” extends through the bottom to restart it. This thing worked fine for 75 years at the company.

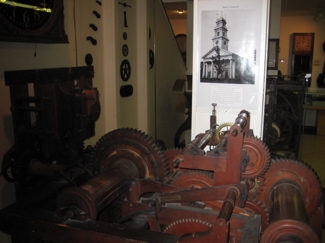

Out of the Barnes Wing and over to the Ingraham Wing, which houses the permanent “Connecticut Clockmaking and the Industrial Revolution” exhibit.

At the beginning of the 19th century almost everything was made by hand and almost nothing was made by machine. By the end of the 19th century most items were made by machine and practically nothing was made by hand. The American clock industry played an important role in that transformation often called “The Industrial Revolution.” At the end of the 18th century clocks and watches were made in America and in Europe one at a time by the local clockmaker. The time consuming process of molding parts from brass, filing them and fitting them together made these timekeepers expensive.

Eli Terry a master clockmaker from Terryville, CT experimented with the production of wooden clock movements and in 1807 he received a contract to produce 4,000 clock movements in 3 years. Using local water power to run his machinery, local carpenters, Silas Hoadley and Seth Thomas, to produce the parts, and the concept of interchangeable parts, he completed the contract on time. His movements were the first complicated mechanical mechanisms with truly interchangeable parts.

This exhibit tells the story of Eli Terry’s effort and the subsequent developments that lead to the growth of the clock industry in Western Connecticut.

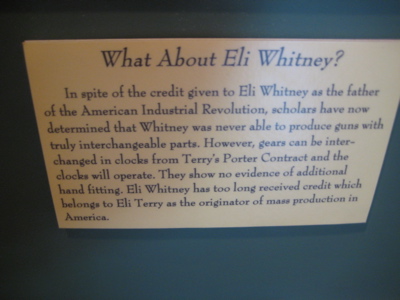

Hmm, I wonder how much more you want to know about Eli Terry. I suppose it would do us all some good to delve a little further into this man, if only to arm ourselves with some facts about Terry when we hit the Eli Whitney museum in Hamden.

Why? Oh, only because Whitney has long been credited as the father of American mass production methods when in fact his guns did NOT contain interchangeable parts whereas Terry’s clocks most certainly did. (This, all according to a sign at the museum.)

Eli vs. Eli! Only here in Connecticut’s history, folks. I, for one, would get that pay per view.

There is a great page on Terry on Wikipedia. I’ll just highlight and pull out some facts I found interesting… Like, how in 1801, Terry was granted a patent on an equation clock. This was the first patent for a clock mechanism that was ever granted by the United States Patent Office.

Later, Terry designed a new kind of clock, intended for mass production from machine-made parts that would come from water-powered machines ready to go into clocks without any additional cutting by skilled workmen. Terry’s great innovation was the design of an escapement and verge adjustable by a skilled craftsman to allow for the slight differences in the mass-produced wooden clock wheels.

The mass produced wooden clocks manufactured from interchangeable parts that poured from Terry’s factory beginning in 1816 were the world’s first mass produced machines made of moving parts. They were also the first mass market complete machine to be offered to American consumers, or consumers anywhere on this planet.

Okay, that’s enough (but really, you should go to that Wiki link. Eli Terry – AND all his apprentices and business partners had a hugely lasting effect on Bristol, Waterbury and Plymouth.)

The room contains a very professional and informative collection of the history of not only clocks, but local manufacturing in general. Several displays follow the path of Terry’s revolutionary idea, noting such steps as the development, distribution, specialization vs. standardization and portability. Displays describing the inevitable imitation and the cost-saving outsourcing are interesting as well.

One particularly fascinating display showed some of the clock industry’s influence on other inventions. The timers in artillery fuses used recent clock parts originally as did many early mechanical toys, oven timers, and strangely, perfume squirters:

In fact, the E. Ingraham Company, which was built entirely on clocks and whose founder started this dang museum, pretty much switched over to the far more lucrative fuse industry to become part of the industrial war complex. Who knew?

Also, who knew there was an entire downstairs to this place. It’s not even on the little handout with the map of the museum!

On the way down the stairs, I passed a huge 2 or 3 story pendulum for some giant clock that I didn’t bother to notate. I think it may be from some local church made by one of the famous local clockmakers.

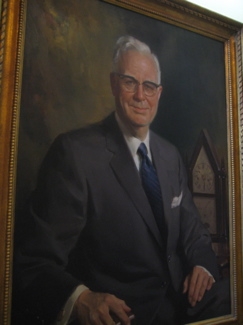

Also on the stairwell are portraits the key guys in 20th century local clock making. There’s ol’ Edward Ingraham, great grandson of the “original” Elias Ingraham who was of course one of the industries originators. He was a clock collector who personally started this museum – a museum in which he had a heart attack and died in 1972.

I guess he had a bad ticker. Too soon?

Next to Ingraham is William Edwin Sessions whose family owned the renowned Sessions Clock Company. Does the name sound familiar? It should – for we had a grand old time at Sessions Woods Nature Center up in Burlington. If you go to that post’s comments, a knowledgeable reader wrote up a bunch of info on the Sessions family including the following:

“Sessions Woods was donated to the United Methodist Church by the Sessions Family (former owners of the Sessions Clock company) who were members of Prospect UMC and it was to be used as a camp. The conference sold it to The State of CT because they needed the money. They did have a better offer from a developer but decided to sell it to CT so that it would be kept as open space for people of the state to use.”

It goes without saying that I like this guy. He also died of a bad ticker in 1920… Too soon?

Once down in the basement exhibit, I was once again blown away. The theme seems to be 20th century clocks and watches and man, they’ve got a ton of ’em. Have you ever actually seen an atomic clock? Well, now you have:

Have you ever actually wondered what the heck an atomic clock is? Well, an atomic clock is…

a type of clock that uses an atomic resonance frequency standard as its timekeeping element. They are the most accurate time and frequency standards known, and are used as primary standards for international time distribution services, and to control the frequency of television broadcasts and GPS systems.

Atomic clocks do not use radioactivity, but rather the precise microwave signal that electrons in atoms emit when they change energy levels. Early atomic clocks were based on masers. Currently, the most accurate atomic clocks are based on absorption spectroscopy of cold atoms in atomic fountains such as the NIST-F1.

National standards agencies maintain an accuracy of 10-9 seconds per day (approximately 1 part in 1014), and a precision set by the radio transmitter pumping the maser. The clocks maintain a continuous and stable time scale, International Atomic Time (TAI). For civil time, another time scale is disseminated, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). UTC is derived from TAI, but synchronized, by using leap seconds, to UT1, which is based on actual rotations of the earth with respect to the solar time.

Got all that? Good, because we’re moving on to another fascinating piece of clock history: Railroad Time. Notice on the clock to the right that “Local Time” is 8 minutes ahead of the “Railroad Time.” Let’s learn together…

Prior to 1883 towns in America observed “local time” based on its median with the sun – exactly overhead at noon. As the sun moves consistently east to west, noon varied as one traveled east or west. This played havoc with the railroads as the time would be slightly different in each town they passed through. The railroads successfully pushed for the standard time zones which were established in November of 1883.

Locals everywhere protested this change, but the consensus held – yet was only incorporated into federal law in 1918. Connecticut’s Seth Thomas Clock Company acquired the rights to manufacture clocks which had two regulators, showing two times as many towns resisted the change.

After about ten years, everyone gave up and railroad time became known as… Yup, Standard Time. The clock at the museum is correct, as Bristol lies 2 degrees east of the 7th meridian on which Eastern Standard Time is based.

How about this clock?

That is an original 1955 US Naval Office “Master clock” responsible for keeping accurate time during the Cold War, so we’d know when to coordinate destroying the commies. Only 12 were made before Cesium clocks proved more accurate.

There was a large collection of Disney and other company branded watches – some of the first licensed items in America (like the Woody Woodpecker watch). And this silver Swiss Favag Master clock, below right? That, my friends, is THE original CBS master clock used between 1962 and 1980 to coordinate the Tiffany Network’s programming.

Amazing.

There are also large display cases with tons of chronometers, alarm clocks, banjo clocks, pocket watches and detailed descriptions of watch parts.

Not to mention examples of the first punch clocks and another clock (below) which had rotating ad space. Can you tell what’s cool about the clock below?

It’s just a clock, yeah, but open the top and there is a scrolling brass braille component which allowed a blind person to tell the time. This one is from 1939 and is one of only a few ever produced.

Phew. Back upstairs, through the gift shop where one can buy American Clock and Watch Museum socks for their newborns, and into the last few exhibit rooms.

And you thought we were done. Ha!

I entered the first of the 4 remaining rooms, pretty much all clocked-out. The first room had… A bunch of clocks in it. All very nice clocks to be sure, but I don’t really remember nor did I take notes on this collection. The room was called “The Clock Shop” for some reason.

But check this one out (below). It’s “the craziest clock in the world!” While that’s quite a bold claim, am I really going to disbelieve anything this place says about clocks anymore?

Around the corner were a couple temporary displays – both incredibly impressive yet again. One was a display case called, “Ancient Timekeeping: Sandglasses, Sundials, Fire Clocks, & Astrolabes.”

This exhibit illustrates the types of devices used to measure intervals of time prior to the development of mechanical means. Highlights include a selection of ancient sundials reproduced by the late Richard F. Bolster (1889-1965) of Forestville, CT, a local astronomer and mathematician; an early, sectional sand-glass with fish skin-covered case; and a Persian astronomers’ astrolabe dating to ca. 1800. Pret. Ty. Cool.

Then there was an entire wall adorned with Ogee clocks. Lots and lots of these so-called OG Clocks. An ogee clock is a common kind of weight-driven 19th-century pendulum clock in a simplified Gothic taste, made in the United States for a mantelpiece or to sit upon a wall bracket. An ogee clock is rectangular, with ogee-profile molding that frames a central glass door that protects the clock face and the pendulum. The door usually carries a painted scene in the area beneath the face. Ogee clocks are one of the most commonly encountered varieties of American antique clocks.

All the names you’re now familiar with made OG clocks – Eli Terry, Chauncey Jerome, (ye of Jerome Avenue fame) and Seth Thomas.

Ogee Clocks

Speaking of Seth Thomas, the museum rightly devotes a room to him as well. However here, the display focuses on Seth Thomas watches, something the company only focuses on for about 30 years.

In 1883 the Seth Thomas Clock Company decided to manufacture watches. The company designed and built the necessary tools and machinery in the machine shop of the the clock factory. A watch factory building was built and opened in the spring of 1884. The first movements were eleven jewels. In 1886, the output of the factory was about 100 movements per day, In 1915, the company ceased watch production. Seth Thomas produced over 3.6 million watches in its short watch building venture.

The museum seems to have just about every model the company ever made; just amazing. In addition to the Seth Thomas watches, there were a bunch of other beautiful pocket watches from the period as well.

I had finally made it to the final room – the “Novelties” room. This was a good way to end my tour I think. I was still blown away by all that I had seen (and have been re-blown away by writing about it all now) so it was good to see some stupid clocks.

Okay, maybe they’re not “stupid.” But some are surely silly.

And I’ve saved the best for last. Hickory Dickory Clocks!

Did you notice the mice “running up” the clocks? And by the way, a sign at the museum suggests that “Dickory/Hickory/etc clock” are just messed up Celtic words mishmashed through the years by kids.

If you read this entire account, you know that I loved this place. Do I love clocks? No. But the American Clock and Watch Museum made my Top 10 of my first 100 Museums list. The history, the excellently displayed artifacts and the impressive collection are definitely worth a visit from just about anyone.

![]()

American Clock and Watch Museum

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Debbie says

Debbie says

November 24, 2009 at 12:17 pmI have to ask – were all the running clocks showing accurate times?

Mike Kelly says

Mike Kelly says

December 31, 2009 at 6:11 pmI was working for a company in East Haven, delivering fireplace parts. I was taking my lunch near a seth thomas store in thomaston. I went in and I decided that if I ever have a son, I should buy him a watch. I was 20 at the time and just out of the army in 1975. I bought a ST pocketwatch that had a train on the back, and a bunch of stuff that on the front that represented the American Industrial Revolution.

I am 55 now, and I am holding that watch in my hands now. I have two sons, so I will be buying another pocket watch for one of them.

I had learned that the company was moving down south, because of lower taxes. I am wondering what happened after that? I look around on the internet to try and find the same watch, but have not found any yet. My watch has never been wound up, ever….but its swiss made innards are sure to function properly.

I will have to visit the Museum someday.

Thanks for your site.

Happy New Year (2010)

Donald Muller says

Donald Muller says

June 2, 2010 at 8:20 amAn answer to Debbie’s question about running clocks at the American Clock & Watch Museum showing accurate times. In fact the 75 clocks that are wound by hand every week are set to show slightly different times so that they do not all strike & chime at once. In the Barnes Wing the tall case clocks are set to go off from five minutes before until five minutes after each hour. This gives the visitor an opportunity to hear the unique tone of each clock. Families with children also have fun trying to figure out which clock will be the next to chime.

briefhistoryofwatches says

briefhistoryofwatches says

January 16, 2011 at 12:29 pmThat was a great reading

carole layng says

carole layng says

May 17, 2011 at 7:25 pmI have in my possion a grandfather clock which was once owned by the late Barbara Heck it has the origonal cat guts and is still in very good condition but does not run. I will try and find out more info, but I do know it was shipped to canada from New York in the 1700, looking for some help with its value??

Steve says

Steve says

May 19, 2011 at 10:49 amThe only help this website can offer you is to suggest you seek answers elsewhere. I don’t know a thing about clocks or appraisals, as this page makes abundantly clear.

Bill McClung says

Bill McClung says

May 23, 2011 at 12:32 pmHi…You show a portrait and mention two people who had protraits hanging…One being William E. Sessions… Is this his portrait or is it Edward Ingraham?

Thanks…

24 May 2011

Tom Navin says

Tom Navin says

September 2, 2011 at 10:49 amI attended Quinnipiac College in the 60’s, when it was in Hamden. I remember a giant 2-3 story pendulum, hanging over a tile floor and it kept time with the earth’s rotation.

I can’t find it on the Net. I thought it was the Peabody, but this was close to 50 years ago and I’m not sure.

Can you help me? I was describing it to my wife and hoped to show her some pictures.

Thanks.

Linda Hard says

Linda Hard says

October 31, 2011 at 8:08 amI loved your article. My grandfather was Edward Ingraham and I loved seeing his picture. He was a very kind man and during the depression did not have to let any of his employees go. He arranged with the merchants in town to honor special checks from him that would be honored by him when the depression was over. He had very clean windows and floors!

Pierre says

Pierre says

March 3, 2012 at 10:53 pmi like to send you foto from a clock limidet edition so gave me a email adresse and am send some foto to see if is rera one ..bye bye waiting you email

Steve says

Steve says

March 4, 2012 at 11:18 amEn tant que votre anglais est pauvre, je te pardonnerai. Ce site n’est pas affilié à la musée de l’horlogerie. Je ne sais pas quoi que ce soit au sujet des horloges et ne peut pas vous aider. Je suis désolé. C’est la vie.

Yale Landsberg says

Yale Landsberg says

June 3, 2012 at 10:28 amGreat posting!!!

I recently gave my 8 year-old grandson a biography of Eli Terry to read over his summer vacation. And he loves it so much that we are thinking of taking our him and our grand-daughter and driving up from Charlottesville to Bristol to visit the museum.

While there, I would like to donate a standalone version of a patented clock which I invented, housed in a lovely custom John S. Lynch clock case. Don’t know if the museum will want it, but you and your fans might like to know something about my TrueTyme clock and our Better Tymes Project, per http://TrueTyme.org .

Warmest regards, Yale

lendy says

lendy says

March 18, 2013 at 1:52 pmwhen i was a kid, 1970ish, we had a wind up clock with a woody wood pecker on the face, where can i find one like it

Steve says

Steve says

March 18, 2013 at 9:17 pmIn your closet.

Cheryl says

Cheryl says

August 4, 2014 at 11:27 amWas at the museum and saw a clock song on the wall. Any video of anybody signing it. Wonder what it sounds like? Just curious. Post the words if you can.

Patti Philippon says

Patti Philippon says

October 7, 2014 at 1:51 pmThe clock song on the wall in the Museum is “My Grandfather’s Clock” by Henry Clay Work, written in 1876. There are several versions of it online, particularly on YouTube, including one sung by Johnny Cash!

Cynthia Barnes Marty says

Cynthia Barnes Marty says

February 19, 2016 at 12:27 pmI thank you for this site. I am related by blood to Ebenezer Barnes. I lived in Hebron, CT for 8 years and went by the brick building with the lettering “Barnes Clocks” in Bristol. Didn’t think much of it at the time, I was 20 years younger and that was the last thing on my mind, Family heritage! Now I plan to go back and visit this American Clock & Watch Museum in Bristol. My relatives were first settlers in Bristol and they are in the graveyards all over that area. I always wondered why a woman from Wyoming, going to CT with only one friend there, would do so well and feel so good there. They were all guiding me; the Barnes, Blanchard, Glover, and Eddy families.

I will show this to my Grandson.

Jimmy Cook D Cook says

Jimmy Cook D Cook says

May 1, 2019 at 9:49 amHi I have an old Seth Thomas pocket watch. Would really like a little history on it but can’t find anything on this particular pocket watch.can you help. It works perfectly.

Steve says

Steve says

May 2, 2019 at 5:35 amUnfortunately I cannot. I just visit and write about stuff in Connecticut, including museums. I wouldn’t know a Seth Thomas pocket watch from a Timex. Sorry.