I Think I’m Turning Japanese, I Really Think So

Middletown (Google Maps location)

April 23, 2011

Being married to a (south)east Asian woman and having produced two half-Vietnamese sons with her probably gives me a little more leeway with the Asian jokes than the next WASP guy.

Oh, who am I kidding. Aside from comments in the privacy of our home, I’m far less apt to joke about such things. (I know where my banh is buttered.) And so, let’s just move forward with this page about The Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies, which is part of Wesleyan University in Middletown.

As I knew this was a small gallery, I brought Damian along for the ride. Even if he acted up, it wouldn’t be for too long. And, I figured, perhaps he’d get more in touch with his Asian blood and seek some answers to life’s mysteries.

Jumping ahead, that didn’t work out so well… Keep reading.

The Mansfield Freeman Center for East Asian Studies (FEAS) is the home of Wesleyan’s East Asian Studies major. It offers a variety of special programs and resources focusing on East Asia. Although these programs are offered primarily as a service to students and other members of the immediate Wesleyan community, the FEAS’s doors are in fact open to all members of the wider Middletown community. The FEAS’s more publicly-oriented programs–including the colloquium series and art exhibitions–attract visitors from all over the state – Hey! That’s me!

In putting this page together, I’ve come to realize that no matter how smart Wesleyanites are, whoever designed the FEAS website must not be that smart. Dead links, wrong live links, live links that lead to dead links that were live link on a previous page, no sense and no order. I’m sure it’ll be fixed up at some point, but for now… Sheesh.

Not exactly what you’d expect from east Asian efficiency. Especially from an organization with a stunning Japanese Garden with perfect design and layout.

The garden is called Shoyoan Teien and I must admit, I gravitated towards the windows overlooking it before I even checked out the gallery. It’s beautiful. I was eager to “visit” the garden proper, but it’s only rarely open for outside visitors – and today wasn’t one of those days. However, it was open a couple weeks later and I went back – Go here for my visit to Shoyoan Teien. It’s worth it, trust me.

The FEAS also runs a unique outreach program, which enables students from local schools to learn about East Asian culture through hands-on activity workshops, exploring such subjects as music, writing, and calligraphy, food and cooking, martial arts, and the Japanese tea ceremony.

The Center is housed in a very pretty building on the extreme northwest corner of the campus. The young woman in the office couldn’t have cared less that a 6’3” white guy with his five-year-old special needs kid in tow were visiting the Center’s gallery. Because, apparently, tall white guys with difficult children always visit on cold rainy Spring Saturdays.

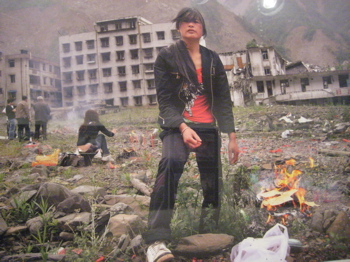

Of course, I like being ignored; I can take my pictures, pose my son – do whatever I want to do. So Damian and I went in the small but very nice gallery to take in the exhibition on display: The Great Sichuan Earthquake

It’s crazy that this earthquake registered only a 3.1 on the Newsertainment scale here in the US. (China doesn’t help matters much, of course, by hiding the true devastation as only Commies can.) But even so, this exhibit focused on the relief effort volunteers, something sort of new in China apparently:

China changed the afternoon of May 12, 2008 at 2:28 when an 8.0 earthquake in Sichuan toppled buildings, destroyed roads and left over 80,000 dead. The government responded immediately with a massive rescue effort, medical help, and then housing and rebuilding; but for the first time, tens of thousands of volunteers from all over China came to the quake zone to help out any way they could. Little noted in the west, the altruistic spirit of the earthquake volunteers, survivors and PLA stirred enormous pride among Chinese around the world. This is the first US exhibition of these photographs by Chinese who themselves participated in the relief work.

Now, I am looking at the booklet the gallery provided which details the relief effort and its importance in Communist China. It details the massive quake and the massive response from China’s army and citizens. And that’s all great and well and good, but I cannot get the story of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei who was arrested a few weeks before my visit to the gallery.

You see, catastrophic disaster isn’t something totalitarian regimes like to publicize. After all, pretty much every single building in the quake zone disintegrated because they were shoddily built – including schools. So Ai Weiwei, who has been all over the news this year (2011) for being a massive outspoken thorn in China’s side, began researching and collecting names of dead children. China didn’t like this, but finally, after having steadfastly refused to do so for a year, authorities released an estimate that 5,335 students died in the quake — a concession that was widely viewed as being forced by Ai’s unrelenting campaign and the work of scores of volunteers on the ground in the earthquake zone.

The very volunteers this exhibit was championing in a different way. They have been collecting names, ages and other details of the dead students and relaying them to the courtyard offices in a Beijing suburb where Ai and a staff of 15 work. “I think the government number is incomplete at best,” Ai said from his Beijing offices. His staff has come up with a separate number — 5,205 — which he estimates accounts for about 80% of the actual student death toll. “It only reaffirms our disbelief in the official numbers … I only feel lucky that we’d started the investigation early enough to know that the government is not telling the truth.”

As you can imagine, this effort wasn’t exactly applauded by the government. He’s since been arrested on trumped up commie nonsense charges – a result of his outspokenness in a country of silence. So while I viewed the poignant, stark and sadly beautiful photos in the gallery, I couldn’t get the Weiwei story out of my head.

Perhaps that’s what was bothering Damian too, I don’t know. But he was off his game during our visit, pitching a few tantrums as only those with his syndrome can do. When Damian gets mad (or sometimes over stimulated or whatever), Damian punches himself in the head and elsewhere. Hard.

I’m used to it. You’re not. But whatever, I still had some poking around to do… I picked up my son and ventured down a dead-end hallway only to return towards the entrance. There was one of those sliding rice paper door things that you see in sushi restaurants separating those private rooms.

“Oh Damian, let’s see what’s in here,” I said, noticing but disregarding the sets of shoes lined up on the floor. Of course, Damian had no interest in seeing what was in there so as I slowly opened the door, Damian began punching himself in the forehead wildly.

As the door opened and I peered inside, four young Asian students were sitting lotus-style either meditating or praying or just sitting quietly. As they methodically turned to look at us – a tall doofy white guy with a little kid silently punching himself in the head – I just as slowly and quietly shut the door without a word as if none of that ever happened.

Meditate on that, East Asian studies majors. Meditate on that.

(I can’t imagine what they said to each other as we left the building and went back out to my car… CTMQ likes to make an impression wherever we go. Though it kind of sucks when those impressions are on little boys’ foreheads.)

So here’s the thing. We get outside and Damian was still upset about who-knows-what, but I plopped him down and took the pictures with the stone lions.

And you, dear reader, would have absolutely no idea what was truly going on during those few minutes of our visit. But now you do.

And now you know why CTMQ and my life is a never-ending adventure.

![]()

Leave a Reply