Stowe Away to This Museum

Hartford (Google Maps location)

September 25, 2010

Warning: Before you read any further, I want to let you know you will be complicit in aiding and abetting a crime. The crime? That of my taking pictures inside the Harriet Beecher Stowe and Katherine Seymour Day houses. Granted, my pictures are even worse than usual as I took them surreptitiously and usually while on the move. Much time has passed since my visit and my writing this (a year and a half, if you can believe it), so I think the statute of limitations has expired.

Warning: Before you read any further, I want to let you know you will be complicit in aiding and abetting a crime. The crime? That of my taking pictures inside the Harriet Beecher Stowe and Katherine Seymour Day houses. Granted, my pictures are even worse than usual as I took them surreptitiously and usually while on the move. Much time has passed since my visit and my writing this (a year and a half, if you can believe it), so I think the statute of limitations has expired.

I’ve executed this type of skullduggery before – almost always out of honest-to-goodness ignorance. But I can’t claim that excuse this time around as my articulate and polite tour guide articulately and politely stopped the group at the front door, gathered us around and told us that we were not allowed to take pictures. No one asked why. I’ve asked why many times in many different contexts and have heard a whole range of inarticulate and often impolite answers. Frankly, none of them make any sense to me.

Actually, as museums come to grips with the reach of social media and websites such as this one, many have relaxed their “no photography” policies. I would guess that if I arranged my visit beforehand and asked permission to take pictures (something which I never really do as I want to have the same experience as everyone else has), I may have been granted permission here… But I doubt it. The Stowe Center and its more popular neighbor the Mark Twain House seem pretty resolute about this rule. Unless…

Unless you are from an idiotic “ghost-hunting” television show for some reason. Those morons with their children’s toys are allowed to film and play out their juvenile fantasies in the Twain and Stowe houses willy-nilly.

Unless you are from an idiotic “ghost-hunting” television show for some reason. Those morons with their children’s toys are allowed to film and play out their juvenile fantasies in the Twain and Stowe houses willy-nilly.

Which brings me to why I have no compunction about what I’ve done. If these properties allow those clowns in to produce their garbage, I will argue with them that my particular type of commentary regarding their museums is simply better for them – commentary which promotes curiosity and learning rather than oogity, boogity and boo. Think I’m crazy? No, The Stowe Center folks are crazy for promoting this nonsense.

Ahhhhh, that felt good. You all still with me? A few of you anyway? Good, let’s check this place out.

The Stowe Center is made up of a visitor’s center, two houses and a beautiful garden. The visitor’s center is sort of a holding pen for tour-takers but provides plenty of stuff to keep everyone busy and interested. It was formerly a carriage house.

The Stowe Center is made up of a visitor’s center, two houses and a beautiful garden. The visitor’s center is sort of a holding pen for tour-takers but provides plenty of stuff to keep everyone busy and interested. It was formerly a carriage house.

A short movie was played, giving us some background about Stowe. There was a focus on her father, Lyman Beecher. Wikipedia has a good page on ol’ Lyman.

Lyman was born in New Haven and had a bunch of kids (most of whom went on to relative fame in their chosen fields) and moved to Litchfield where Harriet grew up. There’s a sign out along route 63 north of the town center commemorating this spot, but I’ve never bothered to take a picture.

Lyman was an integral figure in the “Second Great Awakening” movement of American preachers back then. He was an abolitionist before it was cool and instilled such ideals in his children. Lyman taught his kids that they could “change the world.” And frankly, several of them did – but Harriet is probably the only one you’ve heard about. (The brothers became preachers , oldest daughter Catharine pioneered education for women, and youngest daughter Isabella was a founder of the National Women’s Suffrage Association.)

Lyman was an integral figure in the “Second Great Awakening” movement of American preachers back then. He was an abolitionist before it was cool and instilled such ideals in his children. Lyman taught his kids that they could “change the world.” And frankly, several of them did – but Harriet is probably the only one you’ve heard about. (The brothers became preachers , oldest daughter Catharine pioneered education for women, and youngest daughter Isabella was a founder of the National Women’s Suffrage Association.)

From the HBS website:

Harriet Beecher Stowe published more than 30 books, but it was her best-selling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin which catapulted her to international celebrity and secured her place in history.

But Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not Stowe’s only work. Her broad range of interests resulted in such varied publications as children’s text books, advice books on homemaking and childrearing, biographies and religious studies. The informal, conversational style of her many novels permitted her to reach audiences that more scholarly or argumentative works would not, and encouraged everyday people to address such controversial topics as slavery, religious reform, and gender roles.

Harriet Beecher Stowe believed her actions could make a positive difference. Her words changed the world.

Did they ever. Legend has it that one President Abraham Lincoln said to her, “So you’re the little lady who wrote that book that started this Great War.” No one thinks that’s actually true, but Uncle Tom’s Cabin certainly aroused compassion for slaves and got people talking about the injustice of it all.

Did they ever. Legend has it that one President Abraham Lincoln said to her, “So you’re the little lady who wrote that book that started this Great War.” No one thinks that’s actually true, but Uncle Tom’s Cabin certainly aroused compassion for slaves and got people talking about the injustice of it all.

The Center makes a point to not absolve northerners of being complicit in the slave trade either. In fact, I learned about “negro cloth” and how our very own textile mills sold impossibly crappy near-burlap material to the slave plantations with which to clothe their slaves. Horribly uncomfortable shoes as well.

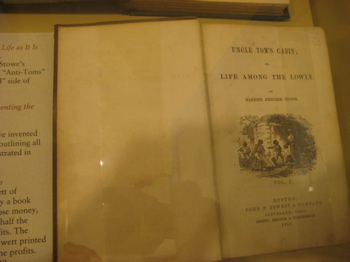

After perusing some Stowe originals like a first printing of Cabin and some awards  she received from around the world, the tour group gathered and we ventured across the grounds to the Stowe house.

she received from around the world, the tour group gathered and we ventured across the grounds to the Stowe house.

The gardens here are beautiful – and historic. Many of them were designed and (perhaps) planted by Stowe herself, as gardening was a major pastime during her day. The Stowe garden is one of Connecticut’s official “Historic Gardens” and yes, I’m visiting all of them as well. You can read more about the Stowe gardens here.

Now would be a good time to also mention that the Stowe house is on two other trails/lists as well: The Underground Railroad Trail (here) and the Women’s Heritage Trail (here) – two more lists I’m completing. Nothing like a 4 for 1 museum visit. Am I right people? People?!

Stowe’s house (incidentally, there is also a Harriet Beecher Stowe House museum out in Ohio as well) is the least exciting of the three houses here in Hartford. It’s a fairly large (for the time) white brick affair, appointed with period furniture and the like.

Stowe became educated far beyond what was typical for girls in her day. Rather than simply learning sewing and cooking, Stowe began her formal education at Sarah Pierce’s academy, one of the earliest to encourage girls to study academic subjects. In 1824, Stowe became first a student and then a teacher at Hartford Female Seminary, founded by her sister Catharine. There, Stowe furthered her writing talents, spending many hours composing essays.

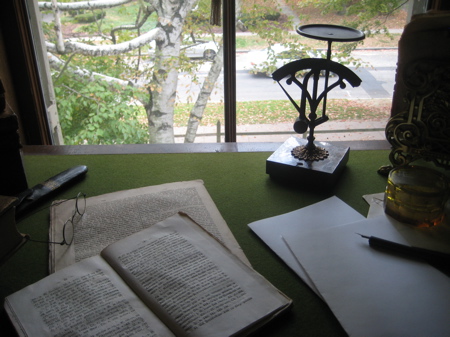

Again, I don’t really have much to say about the house itself due to my lack of decent pictures. We saw the dining room and the parlor. And a bunch of bedrooms. So let’s not focus on my out-of-focus pictures and instead focus on Stowe’s writing career.

Again, I don’t really have much to say about the house itself due to my lack of decent pictures. We saw the dining room and the parlor. And a bunch of bedrooms. So let’s not focus on my out-of-focus pictures and instead focus on Stowe’s writing career.

Stowe wrote about a variety of subjects, from Mayflower descendants to a children’s geography book. After publishing several articles and essays for a variety of journals and newspapers, “The National Era’s publisher Gamaliel Bailey contracted with Stowe for a story that would “paint a word picture of slavery” and that would run in installments. Stowe expected Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly to be three or four installments. She wrote more than 40.”

More, from the HBS Center website:

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, brought not only financial security, it enabled Stowe to write full time. She began publishing multiple works per year including the Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which documented the case histories on which she had based her novel, and Dred: A Tale from the Swamp, another and more forceful anti-slavery novel.

Other notable works include The Minister’s Wooing, which helped American Protestants move towards a more forgiving form of Christianity while simultaneously helping Stowe resolve the death of her oldest son, Henry Ellis Stowe; The American Woman’s Home, a practical guide to homemaking, co-authored with sister Catharine Beecher; and Lady Byron Vindicated, which strove to defend Stowe’s friend Lady Byron and immersed Stowe herself in scandal.

In all, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s writing career spanned 51 years, during which time she published 30 books and countless short stories, poems, articles, and hymns.

Oooh, scandal! For more, I turn to The Atlantic:

In 1869, while Atlantic editor James Thomas Fields was away on a six month journey through Europe, a submission arrived from Harriet Beecher Stowe. By this time, Stowe was already a celebrated writer, well known for her 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and she had written for the magazine before. Her new article, however, gave the magazine’s staff pause. It was a detailed exposé of George Gordon, Lord Byron, including an allusion to the poet’s widely rumored but then-unspeakable affair with his half sister.

Stowe was moved to write the article after striking up a friendship with Annabella Milbanke, Byron’s wife. While Lady Byron was on her deathbed, she had called Stowe to her country estate near London for a “private, confidential conversation upon important subjects.” It was then that Stowe learned Lady Byron’s side of the tumultuous marriage: the lies, the abandonment, the violent outbursts of temper and the “secret adulterous intrigue with a blood relation, so near in consanguinity that discovery must have been utter ruin and expulsion from civilized society.”

The article was published but it severely hurt the magazine’s subscriptions, losing 15,000 subscribers. Stowe stood by her story and even went on to write a book detailing the situation further. In short, Stowe was a tough and resolute cookie.

The article was published but it severely hurt the magazine’s subscriptions, losing 15,000 subscribers. Stowe stood by her story and even went on to write a book detailing the situation further. In short, Stowe was a tough and resolute cookie.

Anyway, back to Cabin, “The first installment appeared on June 5, 1851 in an anti-slavery newspaper. Stowe enlisted friends and family to send her information and she scoured freedom narratives and anti-slavery newspapers for first-hand accounts as she composed her story. In 1852 the serial was published as a two volume book. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a best seller in the United States, Britian, Europe, Asia, and translated into over 60 languages…”

Stowe felt a need to write the serial and publish the books – as a mother and a Christian, she simply couldn’t sit idly by as the injustice of slavery continued in her country. (A country which, in 2012, is filled with people who like to harken back to the old days when the slave-abiding constitution was infallible…)

Stowe felt a need to write the serial and publish the books – as a mother and a Christian, she simply couldn’t sit idly by as the injustice of slavery continued in her country. (A country which, in 2012, is filled with people who like to harken back to the old days when the slave-abiding constitution was infallible…)

Of course, Stowe didn’t live here until after all this stuff. Actually, Stowe didn’t live HERE at first. She built her dream home (called “Oakholm” on the other side of Hartford, but when upkeep and encroaching factories became too much, she moved to the house that is now a museum. (Oakholm no longer exists.) She lived in this house for 23 years.

Stowe wasn’t quite done yet though, as she continued promoting progressive ideals. “She helped reinvigorate the art museum at the Wadsworth Atheneum and helped establish the Hartford Art School, which eventually became part of the University of Hartford. She also continued writing in Hartford with still more success.

So that’s Stowe’s life in a nutshell. Like I said, the house is fairly pedestrian, but I’ll give you some info on it from the HBS website:

The furnishings are a blend of 18th- century family heirlooms alongside Empire and Victorian pieces. Family photographs stand near Stowe’s souvenir copies of Raphael’s Madonna of the Goldfinch and the Venus de Milo. Stowe’s own oils and watercolors attest to her artistic talent. The exterior paint reproduces colors Stowe chose in 1878 and the grounds illustrate her fondness for gardening.

The ground floor of the house includes a front parlor for receiving guests or hosting formal events. The Stowes gathered to read, play games, take tea, or enjoy other family activities in the bright and sunny rear parlor, which features plants growing around windows and picture frames.

The dining room holds Stowe’s table, a set of period chairs and more of her paintings. A Victorian sideboard displays decorative tableware. The kitchen is based on the efficient model recommended by Stowe and Catharine Beecher in their domestic guide book.

The second floor contains family bedrooms and a bathing room. Many objects in these rooms recall the family’s travels, from purchased photographs of classical ruins, to Stowe’s paintings and sketches of Maine, Florida and Scotland. A wardian case, or terrarium, in Stowe’s bedroom reflects her advocacy of bringing nature indoors. Stowe’s hand-painted cottage-style furniture fills the sitting room next to her bedroom. The attic holds five rooms originally used by family members and servants which are not open to the public.

Man, I hope for her sake she paid those servants well.

Stowe was a great writer. And a great painter. And a great human. But interior decorator? Not so much.

After Stowe’s death in 1896 the house was sold, passing through multiple owners until 1924 when it was purchased by Katharine Seymour Day, a grandniece of Stowe and granddaughter of Isabella Beecher Hooker. Day, a painter and preservationist, lived in the house for nearly 40 years. Her decision to make the house a museum resulted in an impressive collection of Stowe and Beecher furnishings, books, manuscripts, and memorabilia.

Which brings me to the Day house across the lawn. It’s beautiful. It’s also probably what many passersby assume is Stowe’s house. Let’s again turn to the Stowe Center’s website for more:

The 1884 Queen Anne style house is one of Hartford’s architectural gems. The wood and granite house is an eclectic grouping of turned balusters, porches, differently shaped windows, and multiple balconies. The original exterior paint scheme, roof shingles, crestings, and finials were restored in 2002. In 1973, an underground vault, storing library and museum collections, was added.

The house is named in honor of Katharine Seymour Day (1870 – 1964), founder of the Stowe Center, grandniece of Harriet Beecher Stowe and granddaughter of suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker. Day, an ardent preservationist and activist, purchased it to save it from being destroyed.

The interior of the 20-room house contains ornately carved cherry, sycamore, and oak paneling with Gothic inspired images and floral designs. Carved faces of the Greenman, a father nature figure, peer from the dining room and parlor. Many of the nine fireplaces showcase tiles from the famed Low Tile Works Company. A massive mahogany chimney breast over the hall fireplace contains squirrels carved in the style of 18th century master, Grinling Gibbons, and ornamentation echoing the exterior roof shingles. The multi-level cherry staircase has two interior balconies, one overlooking a conservatory, and stained glass windows in the hallway, parlor and conservatory.

I can’t believe I missed the squirrel fireplace!

The first floor of the Day House is available for rental and really, if it’s not too crazy expensive I would love to have a CTMQ party there someday. Just remember, no pictures!

And no, I have not read Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Katherine Seymour Day House

…………………………………………………….

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

The House is a National Historic Landmark

Linda says

Linda says

March 1, 2012 at 11:59 amI’ve often thought that the reason a lot of these places don’t allow photography is because they want people to come visit the place rather than just visit via a web page but that’s rather silly if you ask me as wouldn’t photos on a web page actually inspire a reader to want to go see things in person? Of course, I could be thinking too logically here and the excuse they use could be the “We don’t want thieves perusing the pictures and then knowing what to steal when they come in” excuse which again never made a lot of sense to me but then again I like to take lots of pictures to go with posts as it adds more meat and interest so what do I know?

That said, I’ve not been to the Stowe House – or the Twain House – since I was on a 7th-grade field trip way back in 1971 so I’m past due for a visit to both though for the cost of admission, I’d like to be able to take pictures in something other than “stealth mode”. Guess not though, huh? Rats. Hmmm, maybe I’ll skip the trip and just enjoy the visit you’ve provided even with the less-than-stellar quality photos – or I could always see if whatever ghost hunters were there have those episodes on line and visit that way though I’m sure they didn’t really touch on the history of the woman who lived in the house or why she was so important to society and America. Sigh.

Steve says

Steve says

March 1, 2012 at 12:14 pmLinda,

What’s funny about your comment is that those are two MORE excuses I’ve not heard before! Old school excuse is “flash photography damages whatever,” which is simply not true with digital cameras.

A more viable reason that I heard at a very small, rarely visited town history museum was that someone had taken pictures of their stuff and published them without credit or compensation.

Another reason I’ve been told is that nefarious ghouls have taken pictures of antiques or whatever and “sold” them on eBay. I don’t really buy that one though.

Lastly, and the most logical reason to me, is that tour groups need to stay in groups and not get all spread out because some clown (ie, me) is lagging behind snapping pictures all over the place.

When I give talks, I bring up your point – does this website actually LESSEN the chance someone will visit a particular place. I used to have that concern way back in the beginning (when, ironically, no one read this stuff) but not any more. Not after getting so many emails saying how my site has prompted MORE curiosity and “adventure.”

Besides, do you feel like you’ve eaten at the restaurant that was just reviewed in the paper last week? Of course not – you actually have to go and eat there. I see this situation as the same.

Just not as delicious.

Peter says

Peter says

March 1, 2012 at 8:20 pmI would presume that the producers of those ridiculous ghost-hunting shows pay serious $$$ for the right to film at historic sites.

martinet says

martinet says

March 7, 2012 at 11:27 amFunny that you bring this up now. I had a chat with the director of the Saint Joseph College Art Gallery just the other day about putting photos of the collection on the College’s website. I’d wondered about the effectiveness of that (I’ve seen it done for other museums, particularly New Britain and the Springfield art museums) and I asked her, as an insider who’d be “in the know,” if it increases or decreases people’s likelihood of visiting. (My own cynical self had figured it might decrease, especially in the case of art-on-the-wall–after all, what would motivate people to see a picture that they’ve already seen a photo of?) She said, though, that it definitely increases traffic, and I was pleased to be proven wrong. (I personally do know the difference–you just can’t get the light and the texture of most art through a website–but I also know that not everybody realizes that.)

Actually, I’ve dug on museums that post photos online because it’s made it easier for me to recollect things when I’m doing my own obsessive family photo albums (that way, for instance, I can find the name and creator of the paintings that my kids are standing in front of and write them in the album–increases the learning value, gets artists’ names more firmly in the mind, increases likelihood of looking into more of their art in the future). I think CTMQ can have that effect as well for geeks like us.