Zombie Apocalypse Buffet

New Haven (Google Maps location)

October 2011 & April 2019

I always promised/threatened to bring my son Calvin here someday. Well, that day finally came during his 2nd grade spring break. And I was right – he loved it. As a result, you’ll see a mixture of pictures from my 2011 visit with Hoang and my 2019 visit with Calvin. Also, this page encompasses the Yale Medical Library, the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Historical Medical Library and the Harvey Cushing Center. It’s all really cool.

Sometimes I get annoyed with myself when I publish a page title that is so expected. I had a working title of “BRAAAIIIINNNSS!” that sat on my list of “museum visits to write up” draft email for a year. But as I got to typing just now, I realized I couldn’t live with that. Hence, you get something a little more creative. Nonsensical, sure, but creative.

For whatever reason, CTMQ readers over the years have tapped this place as one they erroneously thought I was unaware of and/or one I’d really enjoy going to. One out of two ain’t bad. But moreover, this is the type of place that my wife LOVES. She’s into “gross” stuff and human anatomy and stuff. Except feet. She HATES feet. Yeah, she’s one of those people. She even gets bothered by little babies putting their feet into their mouths.

And so, as has become sort of tradition, Hoang and I took a day off from work in the fall to spend it together, without the boys, doing fun stuff for CTMQ – errr, I mean, for ourselves. We started the day off hiking a section of the Metacomet Trail in a chilly downpour. True to her nature, Hoang was a trooper and smiled the whole time. Afterwards, we went home, got cleaned up and drove down to New Haven. We had a delicious, if a bit cheese-heavy, lunch at Caseus before making some side stops at various Freedom Trail sites on our way to the Cushing Center at the Yale Medical Library.

Like I said, fun was had by all.

By the time we got there, the sun was shining and all was right with the world – and why not? We were about to view some brains.

Although it’s unfair to paint this place as a mere brain repository. There’s more going on here and it’s actually a very well-presented and interesting little museum-like place. It’s a bit of a pain to get to though; after downtown midday weekday parking in New Haven, you must run a gauntlet of security at the Medical Library in order to view the collection. You must also endure the stares of super smart Yale medical students who can smell the non-super smart scent emanating from your non-tweed clothes.

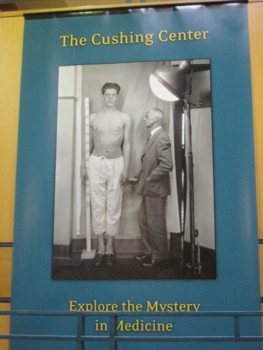

The Cushing Center is in the basement of the library. The journey of the collection to get here is a century-long one and involves lots of very smart, very successful, very rich people helping preserve it along the way.

But first, who was Harvey Cushing?

Harvey Cushing, the pioneer and father of neurosurgery, was born on April 8, 1869 in Cleveland, Ohio. He graduated from Yale University in 1891, studied medicine at Harvard Medical School and received his medical degree in 1895. In 1896, he moved to Johns Hopkins Hospital where he trained to become a surgeon under the watchful eye of William S. Halstead, the father of American surgery. By 1899 Cushing became interested in surgery of the nervous system and began his career in neurosurgery. During his tenure at Johns Hopkins, there were countless discoveries in the field of neuroscience.

In 1913, Cushing relocated to Harvard as the surgeon-in-chief at the new Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. Cushing continued to operate on several hundred patients a year with remarkable results and in addition he was relentless in his recording of patient histories and continued his careful attention to the details and documentation of each surgery.

Impressive. Turns out Cushing was sort of obsessed with record, book and specimen keeping.

Cushing, even as a young man, documented his life in his diaries and letters and often illustrated them with watercolors, cartoons, and sketches of characters and places. This propensity to document carried through his entire career as a neurosurgeon. Cushing meticulously recorded and documented each patient story.

I love this guy! He’d undoubtedly be a CTMQ fan. Hey, don’t laugh, my ex-girlfriend got her MD and PhD at Yale and is now a resident pathologist at Johns Hopkins. So you see, these are the types of people who appreciate me. Or did at one time anyway. (Shout out to Amy.)

One incident in particular drove Cushing to begin to retain all specimens removed during operations or autopsy. Cushing would routinely examine each and every tissue specimen but in 1902, while at Johns Hopkins, the Pathology Department misplaced one of the specimens. This was not acceptable to Cushing and it was at this time that he decided he would retain specimens for further study. So it was this incident that started it all.

I totally get that. Those Johns Hopkins pathologists are a bunch of bums.

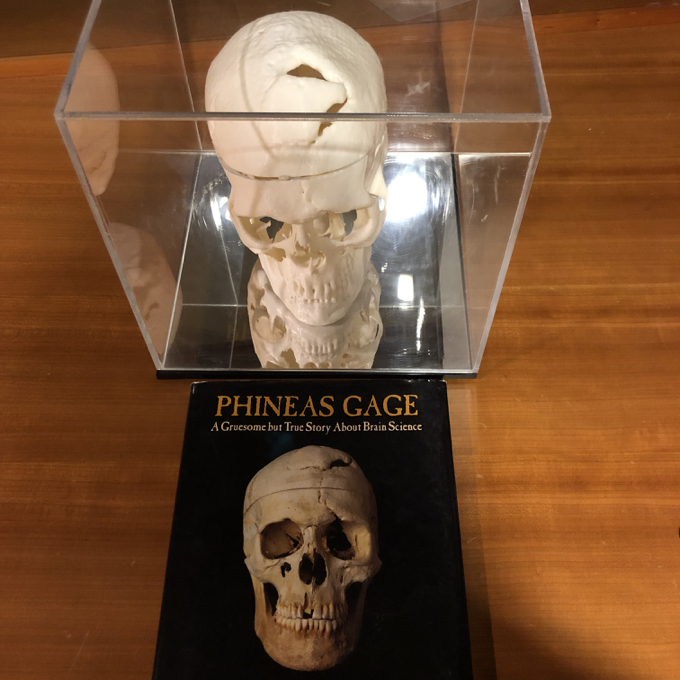

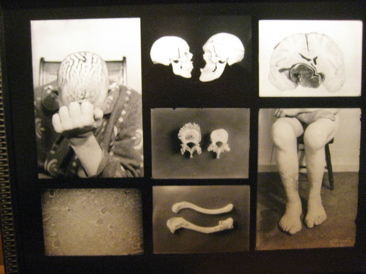

The Cushing Brain Tumor registry, as it is known today, is an immense archival collection of over 2,200 case studies which includes human whole brain specimens, tumor specimens, microscopic slides, notes, journal excerpts and over 15,000 photographic negatives dating from the late 1800’s to 1936. The registry itself is a treasure; a unique resource that documents the history of neurological medicine from its beginning.

The collection remained at Harvard until Cushing’s death in 1939 and he’d always assumed that’s where it would remain. He had written some important medical books before his death and worked very hard to document every single piece of tissue he had worked on. Cushing also pushed for a Medical Library at Yale and learned it would become a reality shortly before he died.

But the collection itself traveled around a few different basements at Yale, at one point ending up in the deep recesses of a dormitory’s basement. And as is typical at Yale:

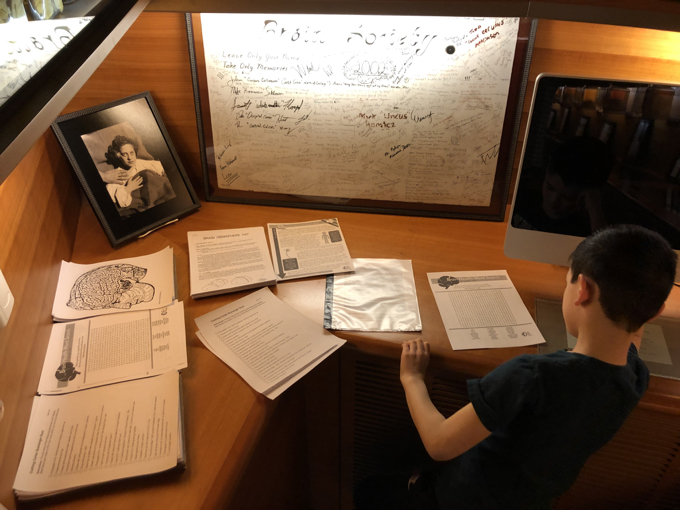

In the early 1990’s the collection was discovered by some adventurous medical students who had to sneak through dark crawl spaces to arrive at the “brain” room. Students would then sign a white board and become members of the “Brain Society” to show they too make the trek to see the brains.

I’d like to make fun of them, but I really can’t. Let’s be honest – I’d totally have been very excited to get my name on that white board. Anyway, after much hemming and hawing, the collection found it’s current location in the Yale Medical Library. And if you’re curious how the specimens were transported:

In preparation for the move each specimen was examined carefully and cleaned by a forensic scientist, Nicole St. Pierre. Housing the specimens in the original one gallon jars, each specimen was removed and the jar filled with new formalin and placed in large white buckets for transportation.

Delicious.

On the way down to the collections rooms, Hoang stopped to mock a skeleton:

Yes, I said mock. That’s just how she rolls.

Once Hoang and I found the collection, we had to wave at the security camera to get buzzed in and then turn on the lights. Eight years later, with Calvin, we had to navigate a maze of stairwells and hallways because of construction. Then we had to do it twice because we were never given a key for entry. We, too, had the whole place to ourselves as well.

The Cushing Center is professionally designed and presented in a very interesting and informative way. It is certainly NOT all about brains. Far from it. Owing to Dr. Cushing’s expansive interests (and capacity to purchase and collect rare artifacts), this is truly a museum of medical history and art. We settled in by watching two videos. The first one was “The Story of Brain Surgery” which was to be expected. The second one was, “The Two-Thousandth Brain Tumor Operation Performed By Dr. Harvey Cushing, April 15, 1931.” It was gross. But hey, the title should have alerted me to that.

The whole room is bounded by a bunch of drawers that the museum calls Discovery Drawers. Each one was like unwrapping a bachelor party gift. Would it be thoughtful and cool or would it be gross? This place is fun.

Open “Drawer 1 Lower” and find “Miscellaneous test tubes, corks, and stains for microscope slides found among materials in the original brain room located in Brady Memorial Laboratory basement.” Open the “Drawer 2 Lower” next to it and boom,

“Disarticulated and Mounted Fetal Human Skeletons”

Move down the wall and open Drawer 6 Upper to enjoy some “Miscellaneous surgical equipment,” get lulled into a sense of security and open the drawer below it for some:

“Human Fetal Skulls at Various Stages of Development.”

You get the picture. Hoang was in her element. I forgot to get a picture of the drawer containing “Human Pelvis Bones of Various Developmental Ages.” though. Those were rad. In 2019 Calvin found some skull caps and jawbones at least:

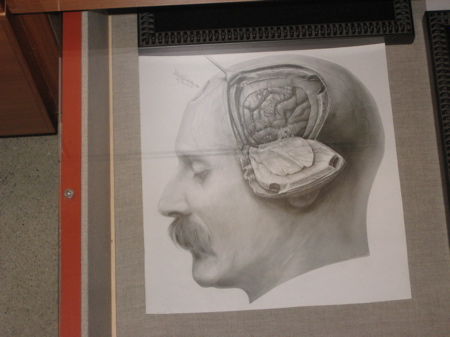

As noted, Dr. Cushing painted some great watercolors too. Of course they weren’t of the River Seine during a sunset, no, they were of people with their brains exposed:

Of course there are lots of things that belonged to Dr. Cushing. Some of them are expectedly mundane, but since this guy was who he was, there are also some really cool, really strange things here too.

Take, for instance, this picture of Hoang casually reading about brain injuries just below a bunch of jars containing brain bits.

To her left, you’ll see a yellowish jar and a picture above it. “So what?” you say? Here’s what that picture and jar are:

The specimen jar contains a steak “signed by Ivan Petrovich Pavlov using the Bovie instrument”; the liver was preserved in alcohol at the Cushing’s request. Cushing writes “so a lobe of calf’s liver was secured from the hospital kitchen. After he tested to his own satisfaction the difference between cutting and coagulation current, Pavlov triumphantly wrote his name on the smooth surface. I asked him whether he wanted me to eat the meat in the hope of improving my conditional reflexes or whether we could keep it in the museum…”

Just two dudes, one whose name is forever associated with conditional response, hanging out eating liver – when one autographs it using a medical instrument used for cutting or coagulation in surgery and then they joke about eating it. My life is so boring.

Moving on… there are tons of historic prints and photographs; everything from ancient Chinese anatomy drawings to 20th century photographs of Cushing’s patients. Some of these pictures are decidedly disturbing, there’s no doubt about that. But from all accounts, Dr. Cushing was very sympathetic and aware of his patient’s needs and abilities.

As parents of a special needs child who displays rather difficult behaviors, every time we explore a place like this we can’t help but think about him in a past generation. Yes, our day in New Haven held the purpose of “getting away” from Damian for a while, but we can’t help it.

Looking at the pictures we can’t help but wonder if his genetic syndrome, which involves self-injury and intense emotional swings, would have been attributed to some sort of brain malfunction. And who knows what would have happened to him just 60 years ago. It breaks my heart.

In fact, I found myself getting a little emotional reading a report in the collection about a child who sound very much like a Smith-Magenis Syndrome kid like mine. (This has happened before; SMS has been around forever but it was only identified in the early 90’s and is still woefully under-diagnosed. Anytime I read this old type of medical stuff I look for the hallmarks – short stature, heavy browline, webbed toes, global impairment, self-injury, difficult speech, etc. I can usually always find it. But I quit reading when I get to the “experiment” or “treatment” part.

I just can’t do it.

Anyway, yes, there are brains here. Lots of brains. Cross sections and full specimens. There are brain tumors here too. You can learn a lot about brains here.

I was quite happy when another couple appeared and seemed to enjoy the collection as much as we did. They were a few years younger than us, but it warmed my heart. They didn’t even appear to be Yalies either; just another couple out for a fun day of tumorific fun.

We went upstairs and still had to check out the expansive Medical Library collections. While not a museum per se, any visit to the Cushing collection NEEDS to be complemented by some time up in the library amongst the other stuff. And there is a lot of stuff.

Actually, I believe there are librarIES as there is a separate Medical History Library as well. I assume that many of Cushing’s historical book collection resides here, if not all of it. There are exhibits in the regular library that sort of bleed into the historical library. It’s all very Yale and very nice and very wonderful…

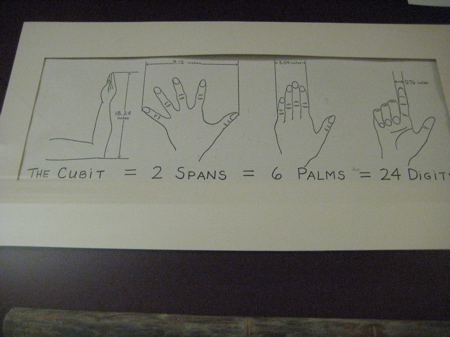

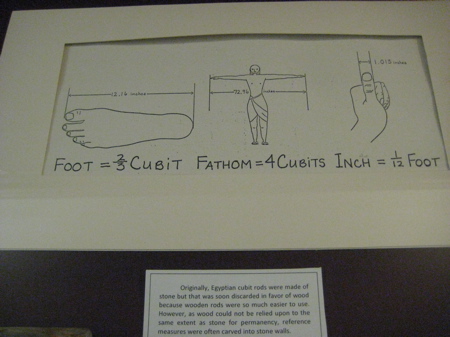

Like the Edward Clark Streeter Collection of Weights and Measures!

[It] is one of the most comprehensive study collections of weights and measures in the world in terms of time period and geography. The weights and scales form the most valuable part: Babylonian, Assyrian, Egyptian, Islamic, Greek, and Roman; weights issued by different cities, especially those in southern France; gold (money) scales; weights and scales used by apothecaries; Nuremberg nested weights, and over 1,000 European individual money weights. The measures, both linear and bulk, range from an Elizabethan corn-bushel dated 1601 to American yardsticks of the nineteenth century and include calipers, squares, bevels, levels, rules, dividers, and measuring gauges.

Our English Units of Measurement…

That we STILL use in the US…

Are idiotic.

There are around 3000 artifacts in the collection, of which only a small selection was being exhibited.The thing about visiting almost any building at Yale is that you’ll find something of museum quality. It truly is an amazing place.

I was mesmerized by the collection. When you stop to think about how “official” weights and measures were created and standardized, it sort of boggles your mind. And here were lots of antique weights and measures that were used as the standards in their periods. I loved it.

There are a bunch of online exhibits as well, many of which are quite interesting. Of course, the historical library also contains a ton of books that are off-limits to bums like us. But it also is home to some collections like the Obstetrical instruments Collection and the Medical Commemorative Medals collection. Yes, you read that correctly… Yale houses a massive collection of, basically, forceps. Check it out.

There are all sorts of brochures and Yale history and periodicals and really, anything having to do with medical history. I’m sure I could have spent much, much longer here but we had a deadline (kids) back home and had to go. There was another small exhibit about Dr. Arnold Gessell who is considered the father of child development studies in the US. (Yale and all their “fathers of!”) He was also, apparently, one of the first professionals to begin recognizing certain techniques that help special needs kids.

So that’s cool.

I enjoyed both of my visits and I know both Hoang and Calvin very much enjoyed theirs as well. The Cushing Center has a stack of children’s takeaways – word searches and other things. I’m not sure how many eight-year-olds come here, and it does prompt some difficult questions from that age. But that should be a reason to take them, not a deterrent

![]()

Cushing Center

Yale Medical Historical Library

Yale Medical Library

Leave a Reply