Most of the other sites are in the north end and while Main Street is safe, some of the side streets are not. Not that anyone is going to go on a walking tour of these sites, other than me.

Let’s get to it.

1. Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Hartford

Bushnell Park/State Capitol

The Soldiers and Sailors Monument (Memorial Arch) honors those from Hartford who served in the Civil War. A marker noting the contributions of African Americans in that conflict has been added to the monument. On display inside the nearby State Capitol are two banners that were used by Connecticut’s all-black Twenty-Ninth Regiment. The Capitol is open to the public.

Photo from CT Monuments

Really, there’s so much more to this arch. And it’s really a shame that the thing was so grandly built (and crashed into by cars all the time), but that the little marker honoring the African-Americans seems like an afterthought. It is still a lovely arch though… with some dead people inside it.

CTMQ visits the arch and Bushnell Park and explains the dead people comment

CTMQ visits the Capitol building

![]()

2. African American Memorial Ancient Burying Ground

Main and Gold Streets

I’ll surely return to this little cemetery for a full report. (Yup, I did.) But for the purposes of the Freedom Trail entry, that’s not necessary. I started my quick Freedom Trail tour of Hartford here, at the locked up Ancient Burying Ground.

During three years of archival research, middle-school students in Hartford and their teacher uncovered evidence that over 300 Americans of African descent were interred in this cemetery, one of the oldest in Connecticut. The students research shed light on the fact that African Americans helped settle the Connecticut Colony. Among the students’ findings were the discoveries that the first enslaved person in the country to sue for freedom and five of the Black Governors were buried here in unmarked graves. To commemorate these forgotten souls, this large slate monument was set in the ground and inscribed with documented names and interment dates. The memorial was dedicated in 1998 with the assistance of the Ancient Burying Ground Association and the Connecticut Historical Commission.

Great article on the monument’s story

Burying Ground Photo Gallery

Stone Field Sculpture right next door

Right across Main Street is…

![]()

3. Amistad Center for Arts & Culture at The Wadsworth Atheneum

600 Main Street

Ah, the Wadsworth. Hartford’s crown jewel museum. It has popped up all over this website. And here it is again, America’s oldest public art museum. But why is it a stop on the Freedom Trail?

The Wadsworth Atheneum houses the Amistad Foundation African-American Collection. This unique collection of Americana is comprised of over 6,000 art objects, posters, broadsides, photographs, memorabilia, and rare books that evidence the many contributions of African Americans to American culture. The Amistad Foundation provides for public access to this collection, along with changing exhibitions and special interpretive programs, including scholarly and public forums and cultural performances, during the year. The Wadsworth Atheneum also maintains the Fleet Gallery of African-American Art to complement exhibitions in the Amistad Gallery and to further illuminate the role of African American visual artists in American art and culture.

Fair enough. I think with the Capitol, the Arch, a walk through Bushnell Park to Gold Street, a tour of the Burying Grounds, and then the Wadsworth, your day is complete. But as far as the Freedom Trail is concerned, it’s not.

And since I insist, buckle up baby, we’re crossing I-84…

![]()

4. Marietta Canty House

61 Mahl Street

Here’s the deal. There are a couple of these Freedom Trail places located in the worst 5 square blocks in a very tough part of Hartford. Slowly driving around taking pictures not only arouses the suspicion of cops, but also of the locals who have a very bad reputation.

Imagine the following conversation:

Cop: What are you doing driving around here so slowly? Looking for something?

Me: Yes. I’m doing a drive-by shooting – errr – with my camera! I swear!

This first site and the next one are the diciest by far. I picked up the Canty house last summer when I was cutting through and had randomly remembered the address…

So what did I risk my well-being for to take this picture?

Marietta Canty (1905-1986) was an American of African descent who, although she received critical acclaim for her performances in theatre, radio, motion pictures, and television, was limited to portraying domestic servant roles throughout a professional career spanning the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Movies in which Canty appeared included The Spoilers, Father of the Bride, and Rebel Without a Cause. In accepting such roles and performing them with dignity, Canty, like other African American actors and actresses of her day, maintained a presence (although circumscribed by prejudice) for minority performers in the entertainment industry. She assisted in paving the way for successful future African American artists of radio, stage, and film. Canty’s political and social activism in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s following her retirement from the entertainment industry further increased her status as a pioneer in advancing opportunities for women and minorities.

Now back to my dreary April Tour…

![]()

5. Frank T. Simpson House,

27 Keney Terrace

After driving up Main and turning down Mahl Street, drive five blocks and take a right onto Edgewood. Oh yeah, please be careful not to disturb the crime scene from the murder on Enfield Street only 8 hours earlier. Though the helpful police man was sure to block any attempts to do so:

Another senseless murder in the North End

The Hartford Courant

8:38 AM EDT, April 3, 2009A man was shot and killed in Hartford early this morning, police said. Police went to 13 Enfield St. around 2 a.m., where they found a man who had been shot several times. The man was taken to St. Francis Hospital and died just before 6 a.m. His identity has not been released.

The cop also gave me quite a glare, as let’s be honest, the only faces like mine around here are idiots looking to score some heroin – and believe me, I saw several opportunities to score. Add to it my slow driving looking for addresses and, well, it’s a wonder I didn’t at least get asked a few questions.

Anyway, the short block that the Frank T. Simpson House sits on is actually pretty nice though I wasn’t too uncomfortable snapping my picture of it. There was a heated argument on the next block so I didn’t hang around too long and got back to Main Street.

Dr. Frank T. Simpson was born in Alabama in 1907, graduated from Tougaloo College, and moved to Hartford in 1929. He was active in social work in the city and in January 1944 became the first employee of the Connecticut Inter-Racial Commission, one of the first state civil rights organizations in the United States. Simpson eventually became executive secretary, and during his years with the agency, now known as the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities, he worked to end discrimination in education, housing, unions, and employment. Simpson purchased this house in 1952 and resided there until his death in 1974. Built in 1913 near Keney Park (then under construction), the house is on the National Register of Historic Places and is privately owned and not open to the public.

![]()

6. Union Baptist Church,

1921 Main Street

The next three stops are all churches – all within sight of each other. I have no stories about them at all, so I’ll let the Freedom Trail site speak for them. And by the way, they are on Main Street and while certainly not a vacation hotspot, it’s not really unsafe at all. In fact, I received a few “Good Mornings” and smiles from the friendly folks walking about.

Through its leaders and members, Union Baptist Church has made significant contributions to the early civil rights movement on the local and state levels. The Reverend John C. Jackson, who began his ministry at the church in 1922, worked tirelessly to open up employment opportunities for African Americans, especially for teachers and social workers. C. Edythe Taylor, a member of the church, was the first African American teacher in the Hartford public school system. Other members were the first African Americans in the city to serve on the school board, on the welfare board, and with the police department. In 1943 Jackson helped establish the Connecticut Inter-Racial Commission, now the Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities. The church is a life member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and created the local chapter of the Urban League. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places.

![]()

7. Faith Congregational Church (Talcott Street Congregational Church),

2030 North Main Street

Another church…

In 1819 Hartford’s African Americans, rejecting being seated in the galleries of white churches, began to worship by themselves in the conference room of the First Church of Christ. Later established as the African Religious Society, the group built a church at 30 Talcott Street in 1826 and soon became associated with the Congregational denomination. By 1860 it was known as Talcott Street Congregational Church. In 1840 the church opened one of only two district schools in the city where African American children could study free of harassment by white students and teachers. Hartford poet Ann Plato and photographer Augustus Washington were among the teachers at the church’s school. Also associated with it were Amos Beman and James Pennington, two of the most prominent African American leaders in the United States. On November 19, 1953, Talcott Street Congregational Church merged with Mother Bethel Methodist Church to become the present Faith Congregational Church. The building at 2030 Main Street was purchased and renovated, with the dedication taking place on June 13, 1954. The church is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Article on this church’s history

![]()

8. Metropolitan A.M.E. Zion Church

2051 Main Street

And another…

When the first African American church in Hartford separated into two churches in the early 1830s, one became the Talcott Street (now Faith) Congregational and the other the Colored Methodist Episcopal (now Metropolitan). The first pastor of the Methodist church was Hosea Easton, an early African American protest writer, who raised funds to replace the church building when it burned in 1836. The new structure on Elm Street also provided a school for African American children. By 1856 the church was located on Pearl Street and known as the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Society. In 1924 the church building was sold to the City of Hartford. The congregation relocated to Main Street by 1929 and was later incorporated as the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

![]()

A short walk south down Main gets you to the last part of my day’s North End journey. I didn’t explore the grounds because – and this is true – I saw several junkies/hookers/johns/etc’s milling about in the trees. Gross.

9. Old North Cemetery,

North Main Street

Located in the center of this cemetery are the graves of a number of African Americans who served in the Civil War. These can be found by taking the entrance next to the building on Main Street and following the paved drive to a path. Between this path and another located a short distance to its right are stones marking the burials of soldiers who served in Connecticut’s all-black 29th Regiment. Although many headstones are missing, at one time there were at least 26 military issued headstones for the 29th Regiment soldiers buried here. There are also graves here of African Americans who served in other Civil War units, including at least four from the 31st Regiment U.S. Colored Troops and nearly twenty from other Colored Troops regiments. The stones provided by the military can differ from one another but are usually made of marble or granite, stand upright and have a rounded top. The war or the soldier’s name generally appears at the top of the stone, with the company, regiment, date of death and soldier’s age listed underneath. Nearby is the stone of James Law, with the inscription: “Born a slave in Virginia, Died in Hartford 1881, the Freedman of the Lord.”

![]()

10. Wilfred X. Johnson House

206 Tower Avenue

Wilfred Xavier Johnson was born in Dawson, Georgia, the son of Eugene and Griselda Johnson. His family came North in 1925 during the first major wave of emigration from the Deep South. Johnson attended school in Hartford and graduated from Weaver High School in 1939. During his high school years, he worked after school as a messenger, or “runner” for the Hartford National Bank in downtown Hartford.

After serving as a dental technician in the U.S. Army during World War II, Johnson returned to Hartford expecting to begin a professional career with the Hartford National Bank. Such a choice of career was unheard of for African-Americans at that time. At first the bank was reluctant to offer him a career track position, particularly one that involved direct interaction with the public. It did, however, encourage him to continue as a messenger and later as a clerk in the analysis department while he attended Hillyer College and the American Institute of Banking, both in Hartford. In 1955 Johnson was promoted to teller, the first African-American to hold such a position in the state.

Although Johnson continued as a teller at the bank until his death in 1972, he had other business interests in the city. Between 1949 and 1954, he was in business with his brother Howard. They ran a haberdashery called Johnson’s Men’s Furnishings at 1930 Main Street. In 1964 Johnson opened a liquor store on Barbour Street known as Spike’s Spirit Shoppe.

Wilfred Johnson entered politics in 1946 at the grassroots level, campaigning in his neighborhood for Democratic Party candidates. At that time most blacks were still solidly Republican, the party of Lincoln. In 1953 he ran unsuccessfully as an independent candidate for city council. Another bid for that office in 1955 also failed. With the encouragement of his political mentor, Judge Boce Barlow, Jr., a prominent black Democrat in Hartford, and William curry, one of the party bosses, Johnson sought the party’s nomination for state representative in 1958 and became the first African-American in Connecticut’s history to be endorsed by the Democratic party. Running in a citywide election, Johnson won handily with the support of an ethnic political coalition composed of Irish-, Italian- and African-Americans. His opponent was another black candidate, the Reverend J. Blanton Shields of Hartford, one of the first two blacks to be endorsed in the state by the Republican Party. The other candidate, who also lost a bid for election, was Mrs. Margaret Ashley of Plainville. Johnson, who was reelected for four consecutive terms and served until his defeat in 1968, also served as co-chair of the third ward in Hartford during this period. As a freshman legislator, he served acting speaker of the house, an honor rarely accorded a new member of the house, and was also appointed a colonel in the Governor’s Footguard. Johnson was the first African-American to hold both of these honorary positions. His promising political career was cut short by his death in January 1972 at age 51. In February of that year, the state senate paid him tribute in an official eulogy and leaders of both parties praised him as “a giant in his ideas, beliefs, and feelings for his constituents.”

Gertrude Johnson, his wife, was also active in city politics and in 1957 was treasurer of the Young Democrats. She was one of the founders of Project Concern in Hartford. Project Concern, a program undertaken in the early 1970’s to alleviate racial imbalance in the state’s public schools, involved the busing of a limited number of black inner-city children to suburban schools.

Still owned by the family, the house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

![]()

11. Lemuel R. Custis Gravesite

Cedar Hill Cemetery

In 1939, Lemuel Rodney Custis was hired ias Hartford’s first black police officer. He left the police force to enlist in World War II and graduated with four others in the first class from Tuskegee in 1942. Custis was assigned to the 99th Fighter Squadron which flew escort and patrol missions in P-40 Warhaws in North Africa, Sicily and Italy form April 1943 to July 1944. He flew 92 combat missions with the 99th Fighter Squadron and received the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism. He later returned to Tuskegee as an advanced flight instructor, eventually leaving the military as a captain.

A memorial marker honoring Custis and the Tuskegee Airmen is located at the entrance of the cemetery – so says the Freedom Trail people. I drove and walked around the whole front area for 20 minutes in single digit temperatures and didn’t find it. But it’s within or very near the scene above. By the way, a tour of Cedar Hill is really good.

![]()

12. Boce W. Barlow Jr. House

31 Canterbury Street

This house was just added to the Freedom Trail in February 2011. After running an errand, I drove the family north of Albany Avenue to pick up this site. We drove past MLK School and to where I thought would be a depressed area. Turns out, Canterbury Street has a bunch of lovely houses. All this about 2 blocks from Mather and Garden Streets… Who knew?

Boce W. Barlow, Jr. (1915-2005) was the first African American in the Connecticut judiciary and the first to be elected state senator in 1966. As a lawyer, prosecutor and judge, he worked for equal justice and assisted in the writing of Connecticut’s pioneering civil rights laws. Barlow was born in Americus, Georgia in 1915, but moved to Connecticut with his family the following year. Like many African American families of the time, they sought better employment opportunities in northern states. After graduating from high school in 1933, Barlow chose to go into the field of law, an uncommon decision in a time when most black leaders were ministers. He graduated cum laude from Howard University in Washington, D.C. in 1939 and was accepted to Harvard Law School where he was one of four African American students in a class of 600. In 1957, he was appointed judge of Hartford’s municipal court, and, later, as a hearing examiner for Connecticut’s Civil Rights Commission. Throughout his career, he was a part of the major social and political reforms that opened doors for the black community and helped to bring them full citizenship status. His home is individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This property is privately owned and not open to the public.

![]()

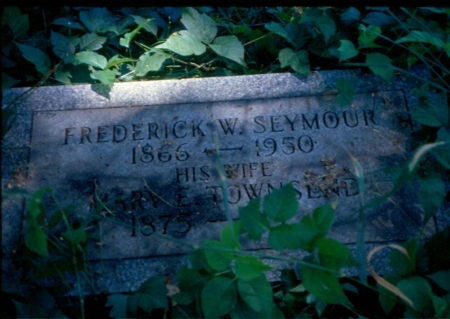

13. Mary Townsend Seymour Gravesite

Old North Cemetery, North Main Street at Mather Street

Hoo Boy. This is a tough one. Old North Cemetery reflects the blight of the neighborhoods around it. The roads aren’t maintained, half the gravestones are knocked over; it’s overgrown and just plain dangerous with a thriving drug trade all around.

But history stops for no one, and neither does CTMQ. But CTMQ does stop for a certain plant. That would be poison ivy. I am highly allergic to it, so once I started poking around looking for the actual Seymour gravesite, I realized it wasn’t really worth it. Especially since the Freedom Trail site has a picture of it – which tells me the thing is totally buried now anyway, as much of this cemetery hasn’t been maintained for years.

Mary Townsend Seymour (1873-1957), a leader and an activist in early 20th century Hartford, battled for equal rights and freedom from discrimination for all African Americans. Her numerous accomplishments include: co-founding the Hartford Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; campaigning for women’s suffrage and running for the Connecticut State Assembly in 1920, making her the first African American woman to run for a state office. During World War I, she helped form a Hartford chapter of The Circle for Negro War Relief, Inc., working to lend support to soldiers and their families. After the war, she became involved in labor issues. She encouraged African American women who worked in tobacco warehouses to unionize for equal treatment and wages and wrote a letter that was published in The Crisis, exposing unfair conditions by working undercover as an employee. She was also a member of the Colored Women’s League of Hartford, which taught job skills to women who moved to Hartford from the South. In 2006, Mary Townsend Seymour was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. She is buried in her family’s plot in Old North Cemetery, which is on the National Register of Historic Places. Follow the drive from the front gate on Main Street towards the back of the cemetery. The drive will turn right and then left, towards the back gate. The Seymour family plot is on the left side of the drive, near a tree.

(Buried under poison ivy.)

![]()

14. Freedom Trail Quilts

Museum of Connecticut History, Connecticut State Library

I don’t know when this got added to the Freedom Trail. Those folks can be very sneaky… Adding sites, moving sites from one trail to another; it’s all I can do to stay on top of them as the only person trying to visit every site.

I visited the Museum of Connecticut History a few years ago (here), before I began actually doing the Freedom Trail. Here’s what I wrote back then:

There is also the Freedom Trail Quilt project and the display of the quilts. These represent an acknowledgment by public and private groups of the great significance of the Freedom Trail story within the history of Connecticut and the nation. I do hope to travel the Freedom Trail myself someday, as there are forty public and private historic properties that form a network which conveys the dramatic and important story of CT’s African-American experience. These include gravesites, monuments, homes and other structures associated with the Underground Railroad, the Amistad case, and such notables as Paul Robeson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Prudence Crandall. Should be an interesting time traveling that “trail.”

Haha, did I say FORTY? How cute of me. There are now well over one hundred.

The Connecticut Freedom Trail Quilts are on permanent display at the Museum of Connecticut History in the Connecticut State Library. And that, for now, completes Hartford!

![]()

CTMQ’s Concept of Freedom Trail page

CTMQ’s Freedom Trail page

Errol D. Alexander, Sr. says

Errol D. Alexander, Sr. says

March 20, 2011 at 12:38 amIt is strange for one like myself, who came to Hartford in the late 1960’s and living there for 18 years to find out how so much of Hartford’s history was covered over by just not knowing about the people and places that contributed so much to the pride and legacy of this country heritage. It is even stranger to find that I knew some of the leaders in the Hartford area and did not give them the respect they deserved by being the first of their kind…. i.e.W. Johnson and Judge Barlow. Thank you for an excellent piece of discovery. Errol D. Alexander, Arrowhead Institute, Tacoma, Wa.

Robin Kerr says

Robin Kerr says

April 20, 2015 at 4:19 pmI live in the area you describe and regularly sit in the “Old North Cemetery” It is NOT as you describe! Though blighted and a area of low incomes, there aren’t shootings all the time, neither the drug activity as you describe. But it’s just the description expected from people who just come into our neighborhoods from their nice suburbs and surrounding towns where the median income level is far above poverty, everyone has a car and very few people are on foodstamps!

Your stereotypes prejudice you long before you came therefore you totally missed being able to see and appreciate the rich experience in cultural diversity that could have been yours. I’m sorry for you and invite you to try it again.

Next time though, leave your prejudices and pre-conceived notions behind. Then you might notice that the North End’s Main Street is home to more than 8 churches beginning at the Windsor/Hartford line all the way into downtown.

Next time, put aside your fear and take the time to walk through the Old North Cemetary, the most prominent of two historic cemetaries on North Main Street, where so many greats buried,Horace Bushnell among others, as well as ordinary citizens.

I challenge you to end your time in the “North End” by stopping for a bit to eat or purchasing a snack at any of the little mom/pop restaurants or stores. Go in with a friendly smile, act like you’re at home and happy to be there and I know you’ll be surprised. Nobody will bother you, in fact, if you’re not looking for trouble, you most likely won’t find any. Instead, your smile and your greeting will be returned.

We’re tired of the people who come into our neighborhoods looking to “buy” or that fear to pass through them on their way to work in the commercial/business district of downtown. All they do is come in, take and leave, hardly ever giving back anything. They know absolutely NOTHING about those of us who live here. If YOU did, your article would have been written differently.

Steve says

Steve says

April 20, 2015 at 8:54 pmRobin,

i appreciate your comment and won’t discount your thoughts at all. I haven’t looked at this page in years, so I just read it, top to bottom. I understand why you are upset, but I really don’t think I said anything untrue or provocative.

I wrote what I saw. A murder scene on Enfield Street. The plight of the homeless. Sketchy people. People with drugs to sell me as I drove slowly around the north end to take pictures. Keep in mind that my driving slowly to take pictures is not an activity that is welcomed or common in the area.

If you knew me, you’d know that a) I grew up in an area similar to the north end, and b) I only want the best for Hartford. It is a mismanaged mess and has been for decades. You fine folks who live there deserve better. You deserve to live in a state like the 49 other ones where the wealthier suburbs “help” out the downtowns not only financially, but in all facets. Your north end schools should be equal to my West Hartford ones. Unfortunately, they are not.

I go to the north end regularly. I go to Scott’s Jamaican on the regular. I used to be friends with Armstrong and frequent his Rajun Cajun. I made several positive comments above. To pretend Mather and Garden aren’t violent is lying to yourself. The violence of the north end is rather contained, and is mostly self-contained. I know this. I go to Hartford regularly – and used to all the time before I had kids.

So I’ve taken your challenge. (Hell, back when I just buzzed my hair, I’d go to N. Main for a $6 buzz rather than paying $20 elsewhere. I think it’s a worthy challenge and one that others should take.

Anyway, Bill Hosley tells me that Old North has been fixed up. Keep in mind I wrote this stuff many years ago when it was totally run down. I can’t keep up with every change across our entire state, sorry.

Anyway, thank you again for reading and your passionate comments. I do appreciate them.

Mike Evans says

Mike Evans says

July 19, 2016 at 7:54 pmPeople always try to talk down the crime of were thier originally from. The north end is one of the easiest larger open air heroin markets in the country. I was thier Yesterday every corner is a drug corner in the north end an area like that won’t get better until people want it to