Brutal… In a Good Way

New Haven

November 26, 2008

Hoang and I had taken the day before Thanksgiving off months before in order to make the drive to my parent’s house in Delaware. Actually, anyone who drives in Megapolis on the day before Thanksgiving is certifiably insane. The plan was to go down on Tuesday, but we lost that vacation day somewhere along the way somehow.

So instead, we dropped Damian off at daycare and made a day of it in New Haven. As usual, we hit Ikea for something or other and then a couple Yale museums.

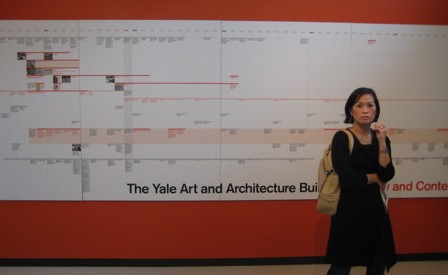

Hoang was happy. For we spent quite a long time at the Yale Art and Architecture Galleries – something which Hoang is really interested in. (I am too for that matter, but my degree wasn’t in architecture and I didn’t appreciate modern design anything before I met her.) Hoang knew who designed the building – and what else he designed and who he studied with and what makes him important, etc. It was a nice feeling to finally bring her somewhere for this website where she was excited to be.

I rather love this picture

You may question the “museumness” of this place; and of course I could slap you for doing so. This one is a no-brainer in my mind. There are large permanent galleries, larger changing exhibits, the building itself is a museum of sorts… It’s a museum, darnit, so there.

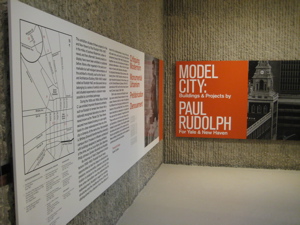

We were fortunate in a sense that the exhibit on display during our visit was all about Paul Rudolph. Why was this fortunate? Because Rudolph happened to be the architect who designed the very building we were in – the Art and Architecture Building (That A&A Building for those in the know. I’ll know if you’re in the know if you’re wearing black and preferably uncomfortable thin-soled European sneakers and funky eyewear).

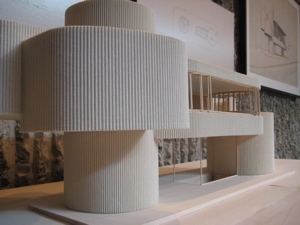

The A & A Building is one of the earliest and best known examples of Brutalist architecture in the United States. It was completed in 1963 and contains over thirty floor levels in its seven stories. The building is made of ribbed, bush-hammered concrete. The design was influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright and the later buildings of Le Corbusier.

When the building first opened, it was praised widely by critics and academics, and received several prestigious awards, including the Award of Honor by the American Institute of Architects. New York Times architecture critic, Ada Louise Huxtable, called it “a spectacular tour de force.” As time went by, however, the critical reaction to the building became more negative. This feeling seems to have plagued much of Rudolph’s work. It has suffered a disastrous fire and a series of renovations that have made it nearly unrecognizable (at least on the interior). The Art department moved out a while ago (having always felt the building was horrible for such endeavors – the painters occupied small studios on the south side of the seventh floor, and the sculpture studio was in a low-ceilinged sub-basement).

Out of the (literal) ashes, the A&A has risen again. The most recent renovation – just about completed as I write this in 2009 – has been enthusiastically embraced and those who care about such things love the building again. Too bad Rudolph didn’t live to see it’s rebirth… Than again, maybe he’d have hated the internal changes.

But maybe not. The negative press about the building towards the end of Rudolph’s life plagued him. “I almost never talk about it,” Rudolph said about the building in a 1988 interview. “It’s a very painful subject for me. I talk quite freely about many of my buildings when asked, but I never talk about this building.”

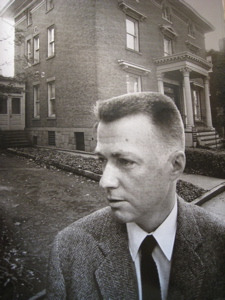

Sort of like Dick Cheney selecting himself as Vice President in 2000, Rudolph selected himself to design the new building for the department he headed since the late 50’s. After mulling over several of his own designs, he went with the most dramatic – a heavy concrete building with elements of many architects.

At least one guy hated it – British architecture critic Nicholas Pevsner.

Pevsner was an advocate of functionalism. “Much to everyone’s surprise, Pevsner turned out to be a wet blanket,” says John Morris Dixon, the former editor of Progressive Architecture magazine, who attended the opening. “His speech warned against the threat of form for its own sake, and reminded everyone that the purpose of a building was to function,” remarks that were interpreted as criticism of Rudolph’s extravagant essay in form.

In short order, the Pevsner view became the prevalent one. Everyone hated the orange carpeting that became filthy after one snowstorm. The windows were terrible and the workspaces provided no privacy. Architect-types lamented the vanity of it, the wastefulness and form over function. My favorite complaint pops up in the many articles I’ve read to write this – the concrete of the walls is sharp and rough and will hurt you if you touch it.

Dean Richard Benson of the School of Art says he won’t miss the Rudolph building. “I’ve taught in this building for 18 years, and it’s an awful place to be,” he says. “It’s difficult to be in a building where if you stumble into a wall you may end up going to the hospital with skin abrasions. Spatially it’s very interesting, but that gets old fast. Who cares if it’s got 36 levels?”

I touched the walls a few times and that is true.

The exhibit during our visit was about more than the building we were in, however. It was about Rudolph’s life and his other work at Yale and in New Haven. He was an architect in the uncompromising mode of Frank Lloyd Wright and stuck to his guns at all costs. He was successful at a young age before becoming the Dean of architecture at Yale.

As noted, he was a polarizing figure; both personally and through his designs. But Yale wasn’t just all about Paul Rudolph, the school commissioned buildings from such notable figures as Louis Kahn, Gordon Bunshaft, Eero Saarinen, and Philip Johnson. New Haven quickly became a “Museum of Modern Architecture” in and of itself.

Not long after Rudolph left Yale in 1964, his career began to run into trouble, and not only from the assaults of post-modernists. “He had some big commissions that ran into trouble in New York and Boston,” remembers John Morris Dixon. “He began to develop a reputation for extravagance and delay.” Hurt and offended by criticism of his work, Rudolph began to withdraw from the spotlight. Until he died in 1997 of cancer at the age of 78, he continued to work — most notably in Asia, where he was commissioned to do a number of skyscrapers — but he became increasingly isolated from the architectural establishment.

The exhibits were really cool and very well presented. Hoang was lost in all the scale models (“I wish I could make these for a living,” she said.) There was a movie about Rudolph and several displays about Yale’s modern architecture. Hoang became wistful while reading about the student projects – the best of which actually gets built in New Haven each year.

For someone like me, who is still in the learning phase about all this stuff, it was still a cool building and experience. I wandered the whole building on my own and found many little exhibits here and there. The orange carpet motif is still dominant throughout and yeah, if I could fund it, I’d love for Hoang to go back to school here for a Masters in Architecture. Maybe some day.

The Dean’s office

We even wandered a few feet into the current dean’s office and spotted a ghost chair, designed by Phillippe Starck. This baby goes for about $410 – and this is the part of modern design I’ve yet to wrap my head around.

And upstairs, out on a patio deck overlooking New Haven? A large array of Frank Gehry outdoor furniture. I just looked it up and what you (barely) see here is a few thousand dollars worth of molded plastic.

I really enjoyed my visit and I learned a ton of stuff, both in visiting and in writing this. It’s also fun going to these places where Hoang loves every minute of it. This is a place to revisit at some point.

![]()

Leave a Reply