Lyre! Lyre! Clavicytherium on Fire!

New Haven (Google Maps Location)

January 29, 2009

Yale is an amazing place. It is renowned worldwide for its academics and famous alumni. That’s great, but what I care about is the fact that the campus houses tons of museums. In fact, the university has more museums than most Connecticut towns.

It’s become sort of “a thing” for Hoang and I to go to New Haven on free days to shop, eat, and hit some Yale museums. This ought to keep all the Yalies who read this site happy for a while. (Ever since my Lewis Walpole Library visit, I get hits from Yale daily.)

To answer your first question – yes, this is most definitely a museum. One of the foremost institutions of its kind, the Collection acquires, preserves, and exhibits musical instruments from antiquity to the present, featuring restored examples in demonstration and live performance. It provides access to and disseminates information about its holdings to Yale students, faculty, and staff; to scholars, musicians, and instrument makers; and to the broader public.

Hey! That’s us! The “broader public!” It’s also quite an old museum collection. Established in 1900, when Morris Steinert presented to Yale his collection consisting chiefly of keyboard instruments, the Collection grew slowly for over half a century largely through donations from alumni.

The acquisition of the Belle Skinner Collection (1960) and the Emil Herrmann Collection (1962) established the position of the Yale Collection as one of the world’s most important repositories of musical instruments, and confirmed its character as a “collection of superlatives,” as an enthusiastic admirer of the Skinner collection once had put it. In 1961 the Collection was moved from its original location under the dome of Woolsey Hall to its own building at 15 Hillhouse Avenue.

Since 1970 the Collection has nearly trebled in size, today comprising nearly one thousand instruments, the majority documenting the history of Western art music.

The previous two paragraphs were taken from the Collection’s website. Yes, it does state that the collection has “nearly trebled in size.” I initially thought that was some sort of musical Freudian slip, but it turns out that to “treble” something is not to make it higher pitched, but rather to triple it. Of course, this being a Yale institution, they opted to go for the far more clever word. And my hat is off to them.

I should also remark quickly about this museum’s location: Hillhouse Avenue. This street was described, according to tradition, by both Charles Dickens and Mark Twain as “the most beautiful street in America.” It is home to many nineteenth century mansions including the president’s house at Yale University. It’s a lovely street to be sure, but that’s a bit of crazy talk.

Once we were welcomed into the building through the stuck door with a big smile and a quick overview of the collection, lights were turned on for us and we were free to roam. We entered a darkened room full of old bells. As we perused, I mentioned to Hoang that in addition to being forced to play an instrument in middle school band (the baritone), I was also stuck onto the hand bell choir at my parent’s church.

I won’t delve into the psychological implications my horrific baritone career (4th-8th grade, RIP) had on my formative years, but I will mention that the thought of me playing bells with my white gloves on positively cracked my wife (flutist all the way through high school graduation) up. My parents met while in the University marching band together and my dad rocks the trumpet at that same church to this very day. My brother was a fairly accomplished trumpeter. I, on the other hand, was miserable every second I so much as thought about playing that miserable beast of an instrument. I better get back on track before I break down in tears…

The roomful of bells is not a permanent exhibit; selecting from over 180 objects in the Robyna Neilson Ketchum Collection of Bells, guest student curator Tiffany Ng ’05 has assembled a wide representation of the bell in a range of cultures as a signal and ritual medium as well as a musical instrument.

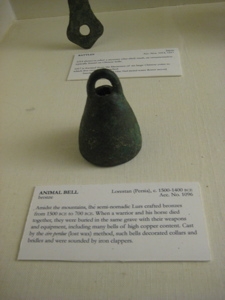

It was pretty darn impressive, I must say. There were some really, really old bells here. Take, for instance, the one above… It’s an animal bell from Persia dating from about 1500-1400 BCE. It was crafted by the Lurs who were semi-nomadic tribesmen. When a warrior and a horse died together, they were buried in the same grave with their weapons and equipment, including many bells of high copper content.

The bell just above is a Swiss cowbell from 1813. I can speak from experience that the Swiss enjoy rather large cowbells. Ahhh, yes… I remember it fondly… After a long day of watching the Tour de France on L’Alpe D’Huez, and an equally long drive to Le Grand Bornand in the Alps, we awoke to glorious sunshine for our drive over to Switzerland. Along the way, we stopped at the Col de la Columbiere and hiked around. And there were docile cows all about with giant Swiss cowbells!

Man, I would like to go back there and eat more croissants. After the roomful of bells, we moved on over to the other first floor gallery. Here, the permanent exhibit of European and American string and wind instruments is located here. The depth of the Collection’s holdings allows for frequent rotation of examples on display.

My favorite, I think, was the “Russian bassoon” (which was made in 19th century Italy, strangely). It had a cool alligator-head thing on the top of it. I guess bassoon players need any edge they can perceive to try to look cool.

Bassoons, flutes, clarinets, violins, other sorts of string instruments from antiquity. This room had it all. They even have a violin crafted by none other than Antonio Stradivari in 1736. Oh sure, the brochure lists a bunch of other important instruments, but who’s ever heard of Jakob Stainer (1661 viol) or Joachim Tielke (1702 guitar) or Litchfied, CT’s own Asa Hopkins (1830 piccolo)?

The room was definitely pretty cool. There is also a display with a couple “frauds.” These are instruments thought to be old and important, but some sleuthing by those who know these things determined them to be fakes. Take, for instance, the clavicytherium pictured here. (Yeah, I don’t know which one it is either, above.)

It was sold as a 15th century antique owned by Pope Gregory XIII. But as anyone could easily discern, the octave span is too small for even a child (127 mm, as compared with the standard Italian octave span of 172mm). I mean, c’mon people.

Disgusted, we ascended the stairs to hit the rather huge keyboard gallery. The museum’s second floor gallery houses the permanent exhibit, “Keyboard Instruments from Four Centuries: 1550-1950,” which includes organs, clavichords, harpsichords and pianos.

With its excellent acoustics this gallery is also used as a hall for the annual series of concerts, many of which feature the keyboard instruments that have been restored to fine playing condition. They have recitals up here all the time, which you can check out yourself by clicking the link below.

After a short while, we were joined by the docent who, honestly, was probably fearful of our antics and immaturity. She happily showed us around and explained a few of the more unique pieces. Amazingly, some of the frailest keyboards were of playing condition and are used in the recitals.

Noted for its balance and depth, Yale’s collection of keyboard instruments is unsurpassed in the world. The Collection’s holdings comprise nearly a hundred examples, including organs, clavichords, harpsichords, spinets, virginals, and pianos from the workshops of the most important makers representing all the major regional schools over a span of three centuries.

There’s a thing called a “double virginal” which of course we snickered at. Did I mention our immaturity? Do I have to at this point? Anyway, it’s true. The one housed here is from Antwerp and if you learn anything today, it should be that a double virginal is a rectangular harpsichord with two independent keyboards, set side by side, and two independent sets of strings. Googling it results in some alternative definitions, as you’d imagine. You can listen to its ear-splitting twang in the links below.

I’d imagine this room is very exciting for musicians. In fact, it was pretty darn cool for this very non-musician. We were fortunate to have the guide open up a bunch of them and show us the intricate craftwork and paintings on many of the keyboards. She did seem a bit confused by the fact that neither of us knew anything about them, nor how to play them as I figure most visitors at least have a little experience. Oh well, I’m used to that.

Again, my ignorance shone at my lack of awareness when it came to the 1620 spinetta made by Francesco Poggio and the 1770 harpsichord by Pascal Taskin. I think I’ll hit up one of the recitals one of these days to hear these old things in all their glory. Like, for instance, the five-octave grand piano made by Johann Jakob Kønnicke in Vienna, ca. 1795, which was recently returned to the Collection after an extensive restoration executed by Rodney Regier of Freeport, Maine. Now in excellent playing condition, the Kønnicke fortepiano is the oldest among the museum’s fine collection of playing examples of European and American pianos from the late 18th through the 19th century. This instrument is representative of the school of piano making established by the Augsburg maker Johann Andreas Stein, whose instruments were championed by Haydn and Mozart. You see.

Back down the stairs we noticed another small display. A bunch of little plastic instruments called Tunettes. I can’t find anything online about them, but I think they were made in Connecticut and they looked like a kazoos. Apparently, they were mildly popular for some reason during the 1930’s and I’m sure they sounded delightful.

I’m sure on your visit to Yale you have the Peabody and the art museums on your list of must-sees. But if you happen to have an extra half hour to spend viewing another of Connecticut’s unique and little-known museums, hop on over to this place and you won’t be disappointed.

![]()

Yale Collection of Musical Instruments

Peder Lettstroem says

Peder Lettstroem says

June 3, 2010 at 3:36 amDear University,

I see a picture in a book that you have a Lyre Guitar from the 18th century.

I have one myself Similar to Anon. Please let me know how many Lyre Guitars there are in the world. Do you have any information about that?

Sincerely,

P. Lettstroem

Steve says

Steve says

June 3, 2010 at 7:21 amPeder,

As you are from Sweden, and you did spend 9 minutes on this page before commenting, I’ll go easy on you.

This blog is not connected to the Yale Music department or the little museum. I wouldn’t know a lyre from a sitar. I don’t even know what you are asking. I just visited the place and wrote my review of it.

Contact the Yale museum directly and perhaps they can help you.