This One’s For the Gipper

Fairfield (Google Maps location)

June 13, 2009

Fortune smiles on CTMQ. Either that or perhaps due to the fact that I’m always going to museums and driving all over the state, I get access to certain places and things that others rarely do. Such was the case on Open House Day at the Fairfield Historical Society. I was spending the day with Rob and Yvonne, two intrepid souls who took a train all the way up from Brooklyn for a day with me. Me! And my nonsense! And they even posed for a bunch of pictures throughout the day!

After spending a good deal of time in the main historical society museum – which, by the way, is right up there with Waterbury’s Mattatuck Museum for town history museum quality – we were told that both the old Fairfield Academy building and the old barn out back were open for the day. “Oh, okay, that’s cool.” It sure was, because I don’t think those buildings are open at any other time during the year. Even way back in 1994, the date of the mimeographed history fact sheet I was given, the Academy building was only open on Independence Day after the ceremonies on the town green.

![]()

Fairfield Academy

Even though the Academy was specifically open for the state’s Open House Day, when we entered the building, the four women inside seemed genuinely bewildered that we’d come to check the place out. They stuttered and stammered and acted as though we were the first group to check the museum out in about 10 years. I suppose there’s a chance that we may have been.

In short order, though, everyone got their wits about them and one woman proceeded to give us a very informative and fun tour. The other women tagged along and appeared to have never been upstairs before. This museum, my friends, is like the Honus Wagner baseball card of Connecticut museums. Or that upside down airplane stamp of Connecticut museums. And not only that, beyond the cool history of the joint, there are two fascinatingly random artifacts inside this place that makes a visit worthwhile for everyone to rearrange their lives to see. Oh just you wait.

Because of the extremely rare visiting hours, this place is pretty much a complete secret. There is nothing – and I mean nothing – online about the old school. All I have is my memory, the yellowed 16 year old copy of its history which was typed on a – gasp – actual typewriter, and my pictures proving I was there.

Actually, that’s not completely true. I also scored a “revised draft” version of the write-up, which appears to have been done on a PC. I only got the first page, but comparing the two documents proves far more interesting than you’d think.

For example, the original 1994 page begins, “Academies, or specialized private schools, proliferated at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th centuries, as the quality of the “district” (public) schools declined. This is happening again today.”

Compare that bit of social commentary with the updated, “Academies, or private preparatory schools, increased in number after the American Revolution.” Sure, the grammar is a lot better, but I think it’s pretty darn funny that they deleted the knock on those terrible public skewls. As if Fairfield’s public school system isn’t one of the best in the country. (Fairfield is a very affluent town and in Connecticut, towns fund their own schools. Disclosure: I am a product of a public elementary, public middle, public Jr. high, public high school and public state University – and amazingly I know how to use a computer to type these words!)

We only got to see what appeared to be a dining room set-up on the ground floor. The local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution meets here and co-owns/manages the building with the historical society, and I think that’s the organization the accompanying women were from. We signed the guestbook and headed up the creaky stairs.

There, the room is set up pretty much as it was back when it was a school with the desks and all that, but there were also period artifacts here and there. Let’s learn more about the school, from the typewritten sheet.

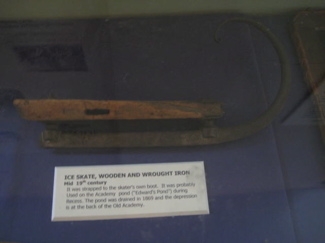

In 1802, some prominent Fairfield citizens founded the Fairfield Academy in order to prepare their sons for Yale and to give their daughters a classical education. $1,085 was raised and the school was erected on the Old Post Road and opened in September 1804 with 60 students attending.

William Stoddard was the first teacher and was paid $500 a year. Tuition for 12 weeks was $4.50 and the student bell-ringer was offered a discount. Many tricks were played with the bell, which still hangs in the cupola. When the school opened, classes began at 6AM. My word.

In 1835 the holidays consisted of Saturday afternoons, Thanksgiving, the Friday following New Year’s Day, Fast Day (proclaimed annually by the Governor), and Independence Day. There were vacations of two weeks in April and two weeks in October.

The teachers often went on to become ministers or college presidents. The first female teacher arrived in 1831. She introduced needlework, resulting in the creation of many stylish bead purses. Meanwhile, the boys were learning stuff like math and English. There are a bunch of the old textbooks on display in the schoolroom exhibit.

Boys and girls had separate recesses, stairs and cloakrooms. The children played on the green, an untidy place frequented by geese, who were often teased, and on the pond behind the school, popular for boating and skating. (Note: When you read poorly structured sentences like the one you just read, that’s just me copying the sheet verbatim.)

Yes, verbatim, like the following:

By 1835 one large stove presided over the center of the schoolroom. Bad boys found that red pepper sprinkled on a hot surface causes cold symptoms. The stove heated only those children fortunate enough to sit in its vicinity, and this seems to have been determined by the amount of wood that a family gave to the school. Pupils “played hookey.” They “fell” into the pond on purpose, hoping to be sent home to change their clothes, but punishment for all misdemeanors was unpleasant. “Feruling,” or striking the palm of the hand with a ruler, and isolation in a cloakroom were common. The coastal boys were said to be wilder than the inland boys!

The building was used for all sorts of civic functions over the years; celebration dinner after the War of 1812, a Red Cross station during WWII, the first home of the town’s first public library, etc.

The school, as first founded, ceased to exist about 1884. Other private institutions of learning such as “The Home Farm School for Boys,” across the street used the building in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After that, the building pretty much fell apart.

In 1920 demolition was considered but the local DAR Chapter was determined to save it, as several members were alumni of the school. The DAR joined forces with the historical society and strengthened stairways, added a kitchen, a back hallway, restored the cupola and added a furnace, electricity and new mantles over the fireplaces. In 1925 the town allowed the DAR and the historical society to jointly occupy the building, but only the DAR chapter really ever did.

The building was moved down the town green in 1958 and like I said, the place is pretty much never open to visit. Which I understand, of course, but here’s what you’re missing:

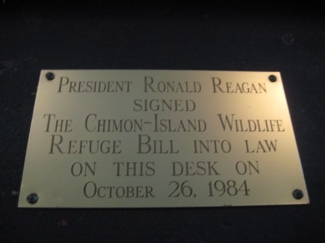

See that desk? That, my friends, is the very desk at which President Ronald Reagan signed the Chimon-Island Wildlife Refuge Bill in 1984! That is so random and I’m sure when the Reaganites get the Gipper onto coins and US bills and Mt Rushmore, this desk will be even more valuable.

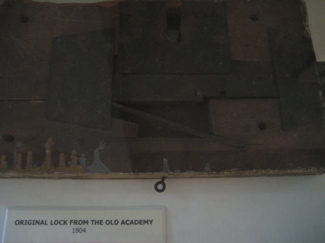

There are a bunch of old things here from back when it was a school. It’s pretty neat, actually, in some ways better than the other one-room schoolhouses I’ve been to for this blog. Stuff like “the original lock from the Old Academy” – something I’m sure the Lock Museum of America in the Terryville section of Plymouth has been drooling over for years. That’s right, in case you didn’t know it, there’s a museum in Terryville that consists of nothing but locks. Lots and lots and lots and lots of locks. I’ve been there; it’s awesome.

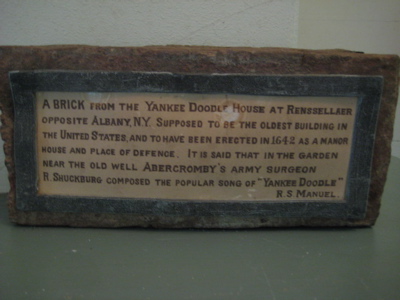

On the wall behind the hallowed Ronald Reagan desk was perhaps an even more random artifact. A brick. But not just any brick, but a brick from the Yankee Doodle House at Renssellaer. The sign said that that building is supposedly the “oldest building in the United States having been erected in 1642,” and also that it was where, years later during the French and Indian War, R. Shuckburg composed the lyrics to “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

The veracity of this latter story is still being debated, but the story is interesting nonetheless – especially as it relates to Connecticut. The Library of Congress notes:

Tradition and other more official sources have it that the American version of the song was written, at least in part, by a Dr. Richard Schackburg, a British army surgeon during the French and Indian Wars while at the home of the Van Rensselaer family. Schuckburg’s lyrics were said to be composed to make fun of the colonials who fought alongside the British troops.

There are many theories regarding the origins of the words “Yankee” and “Doodle.” One theory suggests that “Yankee” (or “Yankey”) was derived from “Nankey,” which can be found in an unpleasant jingle about Oliver Cromwell. Another possibility holds that the Indians corrupted the pronunciation of “English,” resulting in “Yengees.” By the mid-1700s it certainly referred to America’s English colonists.

“Doodle,” as found in old English dictionaries, meant a sorry, trifling fellow; a fool or simpleton. “Dandy,” on the other hand, survived also as a description of a gentleman of affected manners, dress, and hairstyle. All taken, “Yankee Doodle” is a comic song and a parody. Indeed, the British made fun of rag-tag American militiamen by playing “Yankee Doodle” even as they headed toward the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

Of humble origin and perhaps questionable in matters of lyrical “taste,” “Yankee Doodle” has survived as one of America’s most upbeat and humorous national airs. In the fife and drum state of Connecticut, it is the official state song.

From another (now gone) source: “Dr. Richard Shuckburgh, a British army physician, is credited with penning the “Yankee Doodle” lyrics to mock the ragtag New England militia serving alongside the redcoats. As the story goes, Shuckburgh wrote “Yankee Doodle” while at Fort Crailo, across the Hudson River from Albany, after witnessing the sloppy drill and appearance of Connecticut troops.”

You see? We can learn just about anything when visiting small rarely open museums. What, if anything, did we learn at the barn next to the Academy?

![]()

The Unnamed Old Barn

I’m not sure what the story with this barn is, but I’m fairly certain that like the Academy, it’s pretty much never open. But I do think they do presentations when schools have field trips to the historical society, which is in the gleaming new building right next door.

There wasn’t anything I hadn’t seen before at other barn exhibits I’ve been to around the state. But since this was Open House Day, we were able to use some of the implements. The docent was a kindly older gentleman who was happy to have three people moderately interested in old farm implements.

The barn was dark and the summer’s heat had built up inside it rather closely. All the usual suspects were there: old plows, old stools, old scythes, old hoes and rakes. The displays were nicely labeled and corresponding signs allowed us to learn more about the rusty old things. There were also a few signs to educate us on certain things about Fairfield’s agricultural past which we did not know. For instance, I learned that Southport Globe Onions were perhaps the most well-known commercial crop.

They were shipped to the West Indies as early as the 1780’s and reached a height of production shortly after the Civil War. Today the Grange, nurseries and the Haydu Farm, a 21-acre property, are all that remain to reflect Fairfield’s agricultural past. An occupation that employed nine of ten residents is almost nonexistent.

After learning about such things and comparing Fairfield’s onion history to Wethersfield’s much richer onion history (Read all about that here, CTMQ’s visit to the Wethersfield museum), we went back outside to peel some apples and cob some corn.

That was fun. If only because the guide was most perplexed that we wanted to actually use the things.

In the end, I was very glad to be able to visit these oft-shuttered museums. Both are at least partly owned and operated by the Fairfield Historical Society, whose brand new museum is right across the green. The FHS also owns the Ogden House across town, which we also visited on the same day.

![]()

Vicki Kufta says

Vicki Kufta says

February 27, 2010 at 11:02 amI have a lithograph copywrited 1897 by MF Tobin, New York. It is signed by a G.H. Randall. It is titled Old Mansion on the Hudson where Dr. Schuckberry wrote Yankee Doodle. do you have any information on this piece?

I measures about 18 x 9.

Steve says

Steve says

February 27, 2010 at 3:43 pmAnother commenter who didn’t read a word of the page.

Ruth McCormick says

Ruth McCormick says

January 20, 2012 at 7:54 pmI am studying secondary education in the Antebellum Period. I have been looking for museums that are interpreted as secondary schools. Most extant academy buildings are used as historical society headquarters and miscellaneous antique repository or as a community cultural center. Do you know of any other academies/seminaries set up as schools?