Some “Red-Handed” Title Pun

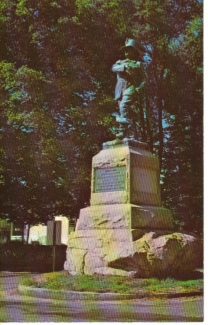

John Mason Statue

Palisado Avenue, Windsor Town Green

I’ve gone crazy lately with multiple posts from Windsor. It stands to reason, of course, as Windsor does stake its claim as Connecticut’s Oldest Town. There are a bunch of museums in Windsor – most conveniently located on the green surrounding this statue – and other fascinating things such as the site of the oldest ferry in the US (right up the road),the oldest legible gravestone in the US and the oldest parish in the new world (both right across the street from the Mason statue).

But, for me, I think this statue of a guy whom you may have never heard of in the middle of Palisado Green is my favorite CTMQ Curiosity of the bunch. His story is interesting on many levels; crisscrossing the state from Windsor to Norwich and back to Windsor again, stirring up anger and passion centuries after his life, he’s been vandalized and pilloried – all this for a guy who, again, you may know nothing about. Let’s change that.

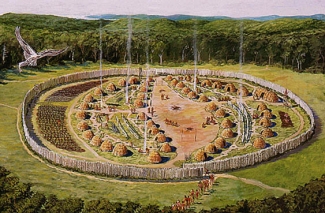

How much do you know about the Pequot War? I’ve mentioned it here and there on CTMQ, but figure it will get the full treatment down the road at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum down on the tribal lands. The war was essentially a four year series of guerilla attacks and skirmishes throughout Connecticut and Massachusetts between the (roughly) English Puritan/Narragansett/Mohegan faction versus the Dutch/Pequot alliance. It was brutal and is often noted as a turning point of colonial fortunes.

It was more or less a gang war over trade routes and materials. In the 1630s, the Connecticut River Valley was in turmoil. The Pequot aggressively worked to extend their area of control, at the expense of the Wampanoag to the north, the Narragansett to the east, the Connecticut River Valley Algonquians and Mohegan to the west, and the Algonquian peoples of present-day Long Island to the south. All of these contended with one another for dominance and control of the European trade.

The Dutch and the English were also striving to extend the reach of their trade into the interior in order to achieve dominance in the lush, fertile region. By 1636, the Dutch had fortified their trading post, and the English had built a trading fort at Saybrook. English Puritans from Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies had settled at the newly established river towns of Windsor, Hartford, and Wethersfield.

The stage was set and things were about to get ugly. In 1634, John Stone, a smuggler, privateer, and slaver, and seven of his crewmen were killed by the Western Niantic, tributary clients of the Pequot, in retaliation for atrocities committed by the Dutch, and by Stone. A principal Pequot Sachem, Tatobem, had boarded a Dutch vessel to trade. Instead of conducting trade, the Dutch seized the Sachem and demanded a substantial ransom for his safe return. The Pequot quickly sent a bushel of wampum, and received Tatobem’s corpse in return.

Then on July 20, 1636, a respected trader named John Oldham was attacked on a trading voyage to Block Island. He and several of his crew were killed and his ship looted by Narragansett-allied Indians who sought to discourage English settlers from trading with their Pequot rivals. In the weeks that followed, colonial officials from Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, assumed the Narragansett were the likely culprits. Knowing that the Indians of Block Island were allies of the Eastern Niantic, who in turn were allied with the Narragansett, Puritan officials became equally suspicious of the Narragansett. Even so, the colonial English response to Oldham’s death, the last in a series of escalating incidents, has traditionally been viewed as the beginning of the Pequot War.

Smaller battles continued, with deaths on both sides. Through the fall and winter, Fort Saybrook was effectively besieged. Any who ventured outside were killed. As spring arrived in 1637, the Pequot stepped up their raids on Connecticut Colony towns. On April 23, Wongunk chief Sequin attacked Wethersfield with Pequot help, killing six men and three women, a number of cattle and horses, and taking captive two young girls (the daughters of Abraham Swain, later ransomed by Dutch traders). In all, the towns lost about 30 settlers.

In May, leaders of Connecticut Colony’s river towns met in Hartford, raised a militia, and placed Captain John Mason, who was not a Puritan, in command. Mason set out with 90 militia and 70 Mohegan warriors under Uncas to repay the Pequot.

And this is where the notorious and infamous John Mason made his mark. Believing that the English had returned to Boston, the Pequot sachem Sassacus took several hundred of his warriors to make another raid on Hartford. But John Mason had only gone to visit the Narragansett, who joined him with several hundred warriors. Several allied Niantic warriors also joined Mason’s group. On May 26, 1637, with a force up to about 400 fighting men, Mason attacked Misistuck by surprise. He estimated that “six or seven Hundred” Pequot were there when his forces assaulted the palisade. Some 150 warriors had accompanied Sassacus, so that Mystic’s inhabitants were largely Pequot women and children. Surrounding the palisade, Mason ordered that the enclosure be set on fire.

Justifying his conduct later, Mason declared that the holocaust against the Pequot was also the act of a God who “laughed his Enemies and the Enemies of his People to scorn making the Pequot as a fiery Oven . . . Thus did the Lord judge among the Heathen, filling Mystic with dead Bodies.” Mason also insisted that should any Pequot attempt to escape the flames, that they too should be killed. Of the 600 to 700 Pequot at Mystic that day, only seven were taken prisoner while another seven made it into the woods to escape.

Eesh.

The Narragansett and Mohegan warriors who had fought alongside John Mason and John Underhill’s colonial militia were horrified by the actions and “manner of the Englishmen’s fight… because it is too furious, and slays too many men.” Repulsed by the “total war” tactics of the Puritan English, and the horrors that they had witnessed, the Narragansett returned home.

The slaughter at Mystic broke the Pequot, and deprived them of their allies. I’ll get more into this war on another post, as I’m supposed to be focusing on this John Mason character. I mean, an honorary statue of a mass murderer who disgusted those who fought alongside him? (By the way, Sarah Vowell also discusses this stuff in her awesome The Wordy Shipmates.

So, what’s the story with the statue?

The statue came to Windsor in 1995 after a long and heated debate with the Pequot Tribal Council and the Groton Town Council over its bloody history and its celebration of a man, whom the Pequots argued was responsible for the near genocide of their tribe.

“That statue is still a lightning rod,” said Kevin McBride, the director of research at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. “It continues to be vandalized to this day.”

A 9-foot-tall statue of Mason was erected and placed at the site of the massacre in Groton (here he is, above, at his former perch in Groton). In 1991, Lone Wolf Jackson, a Pequot tribal council member, petitioned the Groton Town Council to have the statue removed. The statue was subject to repeated vandalism and red paint was spread over Mason’s hands with the word “murderer” scrawled over the statute.

What ensued was years of wrangling between the tribal members and the Town Council over what to do with the statue, and a peace was finally brokered to move the statue to its current home in Windsor, where Mason lived most of his life and is considered to be one of the town’s founders. He also is considered a hero for defending the town of Wethersfield against a raid by Pequots.

“It was certainly a contested issue,” said Jason Mancini, another researcher from the Pequot Museum. “The tribe was adamant to not have that statue there.” Not only was the tribe upset that

the state had designated the site of the massacre as an appropriate place for the monument, but a plaque that characterized Mason’s actions as “heroic victory” was a slap in the face to local Pequot descendants.

“The plaque was very offensive,” Jackson said.

The statue was moved to Windsor in 1995, and the editorializing on the original plaque was discarded and replaced with neutral wording, describing how the statue came to town.

Windsor Historical Society President Christine Ermenc said the statue has become a teaching tool for residents and local students interested in learning more about the Mystic massacre and the history of their town.

While she doesn’t recall specific incidents of vandalism in Windsor, there have been times since she’s been president of the society in which the statue’s hands have been painted red.

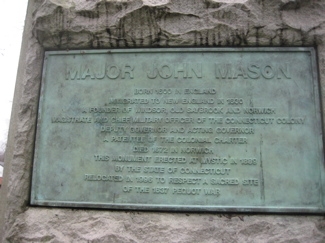

2016 Update: I hope you’re still reading this page, because this is good stuff. Were you, like me, wondering what happened to the original plaque? The one with the insensitive verbiage that was replaced upon the move to Windsor?

Well, I found it:

It was located at the Portersville Academy in Groton! I was given free reign to poke around, so poke around I did. I opened up a closet and – HOLY CRAP! The original John Mason Statue plaque!

I excitedly shared this with a couple friends who care about this stuff and we were all equally giddy.

That’s all I’ve got, but it was really cool finding it.

Lastly, there are two sides to every story – no matter how old. You can find plenty of Mason fans/apologists around the Internet and in the comments below.

![]()

CTMQ’s Statuary, Memorials, Monuments, & Plaques

Hiromi says

Hiromi says

January 13, 2010 at 6:47 pmThank you for the interesting story.

I am analyzing the Pequot War for my senior thesis and found it very interesting!

Well, I could find the current plaque for the Mason monument but I cannot find the old one. Do you know any website or anything that says what was written on the plaque?

Thank you.

Hiromi

Jack Dempsey says

Jack Dempsey says

January 14, 2010 at 6:06 pmLike your thoughtful site—You might be interested in a different conception of what happened at Mystic and in The Pequot War by a look at the samples from “MYSTIC FIASCO: How the Indians Won The Pequot War” (2004) by myself and co-author, archaeologist and painter David Wagner at the above website….The whole work will be posted in revised form this coming spring 2010 at AncientLights.org , as well….Thanks! Best Regards, JD

Laurie says

Laurie says

December 26, 2010 at 8:36 pmHi Steve – nice post! We met a few years back at a museum conference. I love keeping up with your site. Mind if I blog about CTMuseumQuest on our project website? :) The Captain John Mason statue is still a heated issue today, one that has been brought up in recent research during the Pequot Museum’s National Park Service-funded Battlefields of the Pequot War project. It’s incredibly interesting, and we love these points of view. Keep it going, great job!

Jennifer says

Jennifer says

March 5, 2013 at 1:56 amThank you for providing this interesting story from the Pequot War. One small correction: the settler whose daughters were kidnapped was William Swaine (not Abraham). His name appears repeatedly in many histories of Connecticut.

Larry says

Larry says

March 31, 2013 at 12:45 pmThis statue is part of Connecticut History.. It should be preserved for all time…You can’t block history by hiding a statue…Leave it alone!

Jonathan says

Jonathan says

April 12, 2013 at 12:53 pmAs is often the case, we tend to look at events in history with eyes from our current culture, rather than in the context of the time. Observations, judgments and values change over the years and viewed differently within various cultures. It would serve those interested in history well if descriptions of historical events included how those events and their causes, were perceived at the time. While not exonerating or justifying the causes of those events, it would certainly help one understand why things happened the way they did. Context is important and generally ignored so the writer can project his/her own point of view.

Gail says

Gail says

May 6, 2013 at 6:51 amI agree with Jonathan. Two of my ancestors served under John Mason, and although I would prefer to learn that they were great heroes, as anyone would, balanced and fair will do. Politically correct will not.

Steve says

Steve says

May 6, 2013 at 9:13 amI’m not sure Jonathan would agree with Gail as much as she thinks. I agree with Jonathan whole-heartedly. Of course if we were to view these events through the prism of colonial America, our feelings would probably be differnt – as long as we were English or Dutch at least.

Gail, using the Fox News buzzwords in reverse, feels that this page is “politically correct.” Perhaps, in a sense, it is. I just re-read it and can only figure my use of the word “disgusting” in reference to John Mason is what has her upset. I can’t apologize for that. The guy burned up hundreds of women and children on their own land.

Justifying his conduct later, Mason declared that the holocaust against the Pequot was also the act of a God who “laughed his Enemies and the Enemies of his People to scorn making the Pequot as a fiery Oven . . . Thus did the Lord judge among the Heathen, filling Mystic with dead Bodies.”

And when you justify your genocide with a holy book, you are a horrible person, no matter your century.

Tor Hylbom says

Tor Hylbom says

January 16, 2015 at 3:30 pmThanks for the post. John Mason is my 9th great grandfather, and I’ve written on article on my family history blog that traces the history of this line, http://wp.me/P2HCbU-rJ. For the next anniversary of the massacre at Mystic on 5/26/15, I’m planning a blog post to discuss the incident. The title I’ve given it tentatively is “My ancestor Capt. John Mason, who committed genocide in Connecticut, proudly wrote and book about it and was honored with a statue that nobody wanted three centuries later…”. I admire many of my colonial ancestors, but this man is not one that I can take pride in. Genocide is shameful in every era, and this isn’t historical revisionism. We don’t have to guess what John Mason did or was thinking, he wrote about it. The subplot of the orphaned statue is interesting as an example of how views change over time.

L. Armstrong says

L. Armstrong says

March 18, 2017 at 11:12 pmMason is my husband’s 10th great grandfather. When we discovered more about him, I asked my husband, a 30 year Marine veteran, for his thoughts on the politically charged history. He reminded me that in the context of today OR the 1600s, the realities of war are never, ever palatable. It’s war. After years of horrendous attacks upon peaceful settlements — with women and children killed and enslaved — the colonists had to do something. Be reminded, their babies were smashed against trees, women and children savagely tortured and killed as well. There was no shortage of savagery on either side, apparently. Militarily, Mason and his men were outnumbered by thousands. Though as this blog says, the Pequot men were away, Mason and his men might not have known that at the time. For generations, warfare was as much about the shock and awe as a way to end the fight as soon as possible, and an experienced officer would know this. Without enough men, ammunition or supplies to sustain any kind of a prolonged operation, it’s obvious the shock to any remaining natives assisted in preventing more war later…and possible that this terrible massacre actually saved more people from dying down the road, both settlers and natives. That is a very hard reality, but Mason had few choices. And massacres were something people of the 1600s were used to…just look at European history back then, sieges and massacres — La Rochelle in France and the St. Bartholomew massacre, 5,000-30,000 killed in the late 1500s; over 300 settlers in Virginia massacred in 1622 by Powhatans — all brutal. I’m not making excuses, but too few people know the history in detail to understand that this was viewed perhaps differently in their day in that it happened a lot…and we usually have a whitewashed version of it all, to go with our safe, comfortable, snowflake lives. Thank God we have changed in 400 years, mostly.

Mason wrote about the mission in his later years, and what I read appeared humble and not at all proud or crazy but thoughtful and serious. The remainder of his life was spent in service. He was a respected negotiator and protector of peaceful natives, and his sons also worked on their behalf. The New World has a bloody history, but we shouldn’t hide it in a closet. It should be able to be discussed rationally from all angles. I appreciate this blog post, and have given Mason and his men a lot of thought in my genealogy studies. If possible, I’d suggest another post that studies what Mason wrote about the mission. Don’t have it right here, or I’d help out….. Many thanks for explaining the modern conflict. We live in another state and did not know much of the history of CT or truly how much of a role it played in the early years.

KBoone says

KBoone says

April 10, 2018 at 9:33 pmThere is information that prior to the Mystic River incident, that sachems from four tribes approached the colonists, believing their weapons invincible, to ask for protection from the Pequot. There is also in the history of Lion Gardiner an account whereby men had been roasted alive, or flayed alive with tissue from the own bodies forced down their throats. These men apparently did not know that the Pequot warriors had gone elsewhere and per this account believed them to be hiding. You are right, perspective is essential. It was all horrible, a difficult time in Colonial history.

Carol Lawrence says

Carol Lawrence says

August 14, 2020 at 6:08 amI found all the comments very interesting. As a former Windsor resident and current Wethersfield resident, I have heard stories of the Pequot wars. No one wants to hear horrific stories but we weren’t there and we do not really know how difficult it was for early settlers. Fortunately, we are still evolving and I certainly hope are a bit more civil. By talking about history, we do not have to like what we hear but we surely should learn from it so that our behaviors change in a more positive way. Removing statues will not change history but leaving the statues can remind us that we Ned to do better.

Andrew B Hazelton says

Andrew B Hazelton says

August 22, 2020 at 12:48 pmwhen L Armstrong says “After years of horrendous attacks upon peaceful settlements — with women and children killed and enslaved — the colonists had to do something,” he or she is betraying ignorance of colonial history. He or she appears to be mixing up King Philip’s war, which happened forty years after the pequot war, with the pequot war. The pequot war was when europeans taught native americans in southern new england what native americans in virginia and new york already knew by then: that europeans would use ‘total war’ tactics against natives because Europeans did not consider the american natives to be worthy of the scruples of protection of noncombattants that ordinarily were afforeded to european women and children, not only in [most] european wars, but also in native american wars..

If anyone is interested in knowing more about this, i highly recommend one of the acknowledged definitive academic writings about the Pequot war, Adam Hirsh’s article: , “the collision of military cultures in Seventeenth-century new england,” Journal of American History 74 (1988): 1204. Hirsch explains that the very different military cultures of native people and english colonists in seventeenth century new England had a mutual influence on each other: “in the new world, honor was tossed aside—and once the colonists set the precedent, the surrounding Indians followed suit . . . an antecedent of total war had somehow emerged. [Adam J. Hirsch, “the collision of military cultures in Seventeenth-century new england,” JAH 74 (1988): 1204.

The key phrase in the above sentence is “once the colonists set the precedent.” Because once we white people set that precedent, the tribes of southern new england, i.e. the wampanoags and the narragansetts and the nipmucks, followed it, and the mutual brutality that L Armstrong ascribes to the Pequot war played out over and over again, not only in King Philips’ war, but later in many other indian wars in the north american english colonies and in the united states, from western massachusetts all the way to californa.

To quote further from Hirsch: “In 1660 Lion Gardiner ventured that “the Pequit war . . . . was but a comedy in comparison of the tragedies which hath been threatened since, and may yet come.” When King Philip’s war burst across New England some fifteen years later, Gardiner’s forecast proved woefully accurate. From the outset, both settlers and Indians burned villages, destroyed food, slaughtered noncombatants, and abused their prisoners—all with scarcely a trace of moral unease.” [Hirsch, p. 1210-1211]

But the key point here is that burning women and children in their wigwams and shooting the ones that ran out was an “innovation” that was introduced to north america by the english, and to new england by John Mason. (Even Massachusetts’ John underhill, Mason’s comrade in genocide, was clearly a bit uncomfortable with the wanton killing of women and children at mystic village–where the only european death is thought to have been caused by an incident of ‘friendly fire.”.) As Hirsch explains in detail in his article, it is true that under the rules that were observed in the traditional algonquian practice of war, pre-european-contact, noncombattants could be routinely victimized. But while the male captives were often tortured brutally, the typical fate of women and children captives (and indeed the motive for much of the warfare in algonkian culture in the first place) was to be kidnapped in order to be adopted into the society of the victorous band or community, in order to strengthen that community.

IN sum, Knowing the truth of history is sometimes uncomfortable (and not just for white people), but in the words of the historian Jon Meacham (thursday august 20, 2020): “an honest accounting of who we’ve been can enable us to see who we should be.”