ASME Landmark #265 (1970)

Pratt & Whitney Single Crystal Turbine Blade

New England Air Museum

Windsor Locks

Years ago I began my page about a different American Society of Mechanical Engineers National Landmark located at The New England Air Museum thusly:

In a way, this might be the hardest of the CT ASME landmarks to find. This is because it resides in the massive New England Air Museum and, let’s face it, isn’t exactly the draw to the museum. Not with 80 airplanes and a billion other impossibly interesting aviation artifacts located inside – and outside – the museum’s three massive hangars full of exhibits.

My picture of plane looks like the plane where the plaque is now placed. I’m calling it close enough.

I visited the awesome museum in 2012. And at that time only the Hamilton Standard Hydromatic Propeller was an ASME National Landmark. If you think I’m going to go back for the sole purpose of seeing the newer plaque (2018) for the P&W Single Crystal Turbine Blade now, you’re crazy.

Okay, you can be forgiven thinking that I’d do something like that, because I often do things on that order of craziness (See: most of my other ASME Landmark visits). But this time, for once, I’m not. I’ve seen the blades. I’ve marveled at their fine engineering. I just didn’t see the plaque because the plaque didn’t yet exist.

Regardless, let’s learn what the then-future national landmark designation is all about.

The performance of gas turbine jet engines for flight and electrical power generation is dependent upon high temperature properties of super alloy turbine blades and vanes. Turbine blades cast conventionally consist of three-dimensional crystals, or grains, which form during the solidification in the casting of the mold.

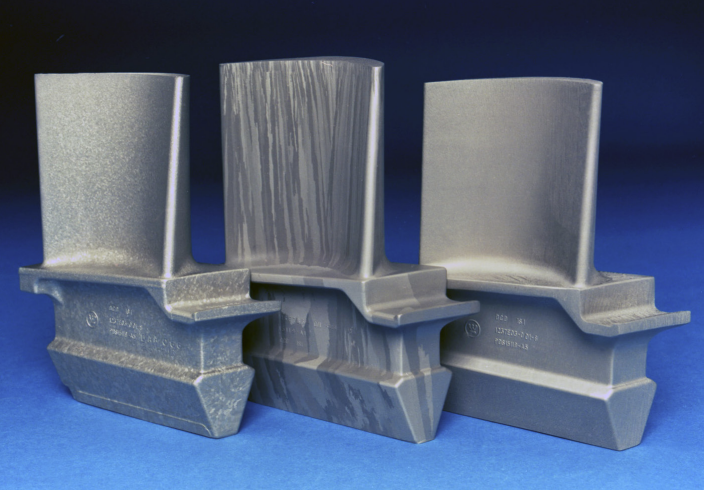

These turbine blades have had their surfaces etched with acid to reveal their inner structure. The one at the far right is a single crystal, the one in the middle is directionally solidified, and the one at the left is made up of

small crystal grains, with numerous boundaries. You see.

Due to this construction, conditions such as void formation, increased chemical activity, and slippage under stress loading can lead to Cavitation, which is spacing within the grains of the mold, shortened cyclic strain life, and stretching under stress, known as Ductility. These activities greatly shorten turbine and blade lifespan, requiring lowered turbine temperatures, and decreased performance.

I am not a mechanical engineer. I never wanted to be one either, though I do understand the above in purely layman’s terms. And I understand the work and process that engineers perform in order to improve things like turbine materials. Just want to give props to the mechanical engineers of the world.

Although, the ASME is doing just that, so I’ll shut up.

To address these deficiencies, Engineers at Pratt & Whitney’s Advanced Material Research and Development Laboratory (AMRDL) developed the Single Crystal Turbine Blade in the early 1960s. Developed from concept to market to production in less than ten years, Single Crystal Turbine Blades were employed in military jet engines in the 1970s, commercial jet engines in 1982, and in land-based gas turbines in 1995.

You see what I mean? Conception to military use took 10 years. Twenty years for commercial use. That’s how these things work. People not familiar with these processes should appreciate that.

And you all should visit the NEAM. Not to see this rather silly plaque, but for the massive collection of planes, engines, and aeronautic history.

ASME Past President Richard E. Feigel (left) pictured with Frank Preli, Chief Engineer of Materials & Processes Engineering, Pratt & Whitney following presentation of plaque.

Fascinating history of the P&W Single Crystal Turbine Blade

CTMQ finds all of CT’s ASME Landmarks

New England Air Museum

My visit to the museum

Leave a Reply