Weston Rocks!

A Professor, A President, and a Meteor, Cathryn J. Prince (2011)

I was “friends” with Cathryn Prince for a year or so before meeting her in person at a book signing in 2011. 21st-century “friends.” In other words, Twitter friends. A Connecticut resident and professor, Prince specializes in writing about obscure moments in history with deep research. She’s written six books as of 2024 and they all contain copious footnotes and sourcing. As a professional researcher myself, I certainly appreciate the work that goes into her books.

But they are not for everybody. I was excited for A Professor, A President, and a Meteor. It checks a lot of boxes for me: I like nonfiction, I like the history of Yale, I love natural history, I love the history of science, and of course I read a bunch of Connecticut-centric books. However, this is not an exciting or very engaging book. I started it in 2011.

I finished it in 2024.

Okay, okay, that’s not fair to Cathryn or to me… although it is true. It somehow got lost in a shuffle and then we moved and it wasn’t until 2024 that I found a cache of “Connecticut books” in a box in my house that I had set aside a decade ago to read for this very website. I do apologize, Cathryn.

The professor was Benjamin Silliman at Yale, the president was Thomas Jefferson, and the meteor was the fireball that hurled a meteorite to the ground at Weston on an early December morning in 1807. The fireball shot across the sky from Vermont, across western Massachusetts, and exploded in a thunderous bang before crashing into farmers’ fields in Weston. This was the first documented fall of a meteorite in the Americas.

And it was a big deal. Keep in mind that if a meteor falls where people live these days, it’s all over social media and the news immediately with all the cameras running 24-7 now. Imagine the hullabaloo in 1807 when people didn’t even know what meteorites were.

A review: Meteoroids, meteors, and meteorites are really names for space rocks at different stages. The ones floating around in space are meteoroids. The ones that enter Earth’s atmosphere and burn up are called meteors. The ones that don’t burn up entirely and instead crash into the surface of the earth are called meteorites.

This book also speaks of meteoritics (the study of the above) and meteoriticists (the people who practice meteoritics). Got all that? Good.

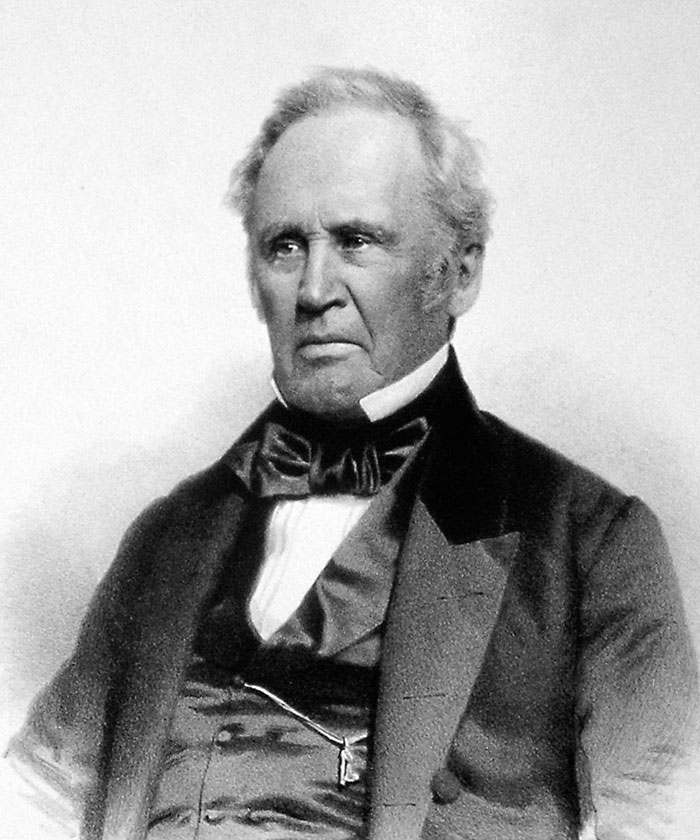

At the time, US scientific study was way, way behind Europe and remember, the country was only just over 20 years old. Silliman had graduated from Yale in 1796 and became a tutor there while studying the law. He passed his bar examination in March, 1802, and was preparing to begin his career when he learned, to his great surprise, that Timothy Dwight, the president of Yale, had other plans for him.

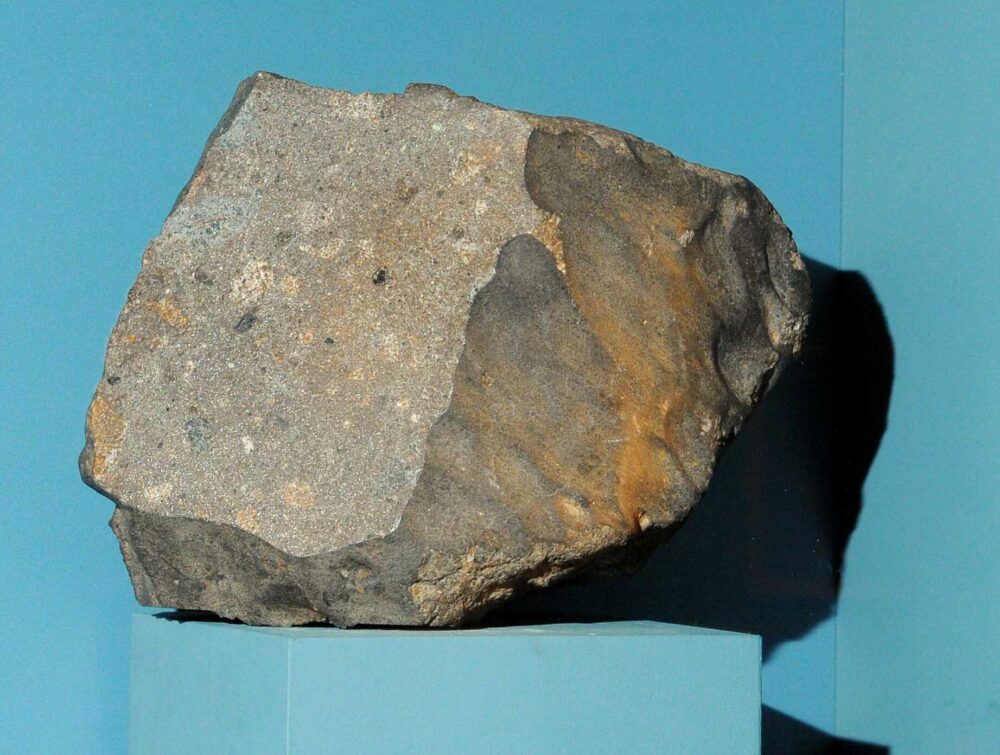

(Part of) The Weston Meteorite, from the Yale Peabody Museum

Dwight was aware of what European unis were up to, and he wanted Yale to catch up in the sciences; notably chemistry and geology. (Harvard was also ahead in the game.) So he basically forced young Silliman to jump on the chemistry ship. There were plenty of lawyers in Connecticut already. Then the meteor hit a field in Weston, about 25 miles from New Haven.

Silliman and his buddy made their way to the crash site and what followed was decades of scientific breakthroughs and fame. He collected the space rocks, studied their chemical makeup and, in 1809, published the first scientific paper in America to win the admiration from the snobs in Europe. Silliman was a fundamentalist Christian, as all Yale men were back then. Prince writes of the disconnect that people like Silliman had to deal with: Yes, God created everything and relatively recently except through this loophole, I can say that these meteors are from space and they are old and the earth might be more than 6,000 years old because in the Hebrew bible they used this archaic word that could mean something that could imply an old earth.

Crazy that people are still playing those games today.

I learned a lot of Thomas Jefferson and how much New England, and especially Connecticut, rather hated him. I learned about Jefferson’s embargo edicts that ruined the Connecticut economy. And I learned about the growth of Yale to not only become the academic institution that it is today, but how early efforts at endowments and wealthy donors building important collections that still exist today.

In fact, the Weston Meteor exists today at the Peabody Museum at Yale as well as the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

(The whole New England vs. Jefferson thing was interesting to me. Jefferson’s election almost amounted to a second American Revolution. The New England Federalists were actively promoting a hierarchical society with a strong central government, tax-supported schools and churches, a national bank, a strong federal judiciary, and tariff system aimed at the expansion of business and commerce. The South, led by Jefferson, favored equality of opportunity, states’ rights, freedom of speech, and freedom of religion! Jefferson argued that religion should be private, and people should be free to practice a faith of their own choosing. Many New Englanders saw Jefferson as a godless threat to the integrity of the Republic.)

To be honest, I’m half with each side there.

By the way, Smuggler’s Notch in northern Vermont is so named because it was a smuggling route from Canada during Jefferson’s draconian embargo.

There’s apparently a “famous” quote misattributed to Jefferson related to this whole episode; something about how “it would be easier to believe that two Yankee professors would lie than that stones would fall from heaven.” This was a big deal quote for many years, but Jefferson never said it.

The book follows Silliman’s impressive career during which he became one of the world’s experts on meteors, chemistry, and geology. He mentored and employed many other future famous scientists like Edward Hitchcock, James D. Dana, and his son Ben Junior. (Hitchcock was a geologist who described southern New England’s glacial past; Hitchcock Lake is named for him and evidence of it can be seen at the Matianuck Sand Dunes in Windsor and at the glacial sediment dam in Rocky Hill.)

Silliman College at Yale is named for him. The mineral Sillimanite is named for him. He transfored science in America and founded the monthly American Journal of Science which is still going today.

I find all this interesting and exciting – I really do! – but the book was a slog in the end. Repetitive and just too lost in the weeds. It’s a really cool story, about a really cool guy, written in a really dry way.

![]()

CTMQ’s List and Reviews of Connecticut Books

Leave a Reply