”Captain Jack Will Get You Enslaved Tonight”

Sufferings in Africa, 1817

By Captain James Riley

I’m not really sure why I decided to read this book for the purposes of a CTMQ “Connecticut” book review. Actually, that’s not true – I know exactly why I did. Back when the boys and I poked around Holy Apostles College in Cromwell, I became enamored with the story of a former sea-faring captain that lived in one of the houses there.

On that page I wrote,

The oldest building here was built around 1750 and still survives. (…) the house was owned by one Captain James Riley – a young sea captain who was shipwrecked with his crew off the coast of Africa. They were taken and sold into slavery. Riley made contact with two Arab traders who led them on a treacherous trek across the Sahara to freedom when an Englishman paid their ransom.

Riley’s account of this adventure, Sufferings in Africa, became a best seller. Abraham Lincoln cited it as a major influence. I bought the book but have not yet read it; it is supposedly one of the great “travelogues” (of a sort) of all time and I’m eager to crack it open.

Which brings us to this page. While the book is hardly about Connecticut, and I can’t get into the habit of reading and writing about every book that has some tenuous connection to the state, I feel that people should know of Riley’s story.

Riley’s account does begin in Connecticut. He grew up in Middletown and offers some early insight into what became our unique town-by-town educational funding system. (You know, the one where the wealthier you are, the better schools your children will attend.)

It may not be improper here to give a general idea of what was then termed a common education in Connecticut. This state is divided into counties and towns, and the towns into societies; in each of which societies, the inhabitants, by common consent, and at their common expense, erect a school-house in which to educate their children. If the society is too large for only one school, it is again subdivided into districts, and each district erects a school-house for its own accommodation. This is generally done by a tax levied by themselves, and apportioned according to the property or capacity of each individual. It being for the general good, all cheerfully pay their apportionment.

“Cheerfully.” I love that.

That passage also gives you a flavor of the sometimes overwrought language and sentence structure employed by Riley throughout the book. Fortunately, his true-life adventure story is a bit more interesting than civic taxes.

[If I may butt in on myself here, the book was actually ghostwritten by Captain Riley’s friend Anthony Bleecker – which doesn’t really diminish the story for me at all. Bleecker read through Riley’s logbook, notes, and recollections to put together the harrowing tale. I learned this after reading the book and am now a bit surprised that the whole adventure, from shipwreck to rescue, wasn’t quite two months – only three weeks of which were under enslavement.]

Riley recounts a few close calls on the sea before jumping right into the fateful passage off the coast of northwestern Africa. Moored on some rocks, he and his crew successfully escape to the shore without much food or supplies. They are met by some thieving Arabs while trying to repair the boat enough to get back to friendlier shores.

With the boat barely sea-worthy, Riley negotiated a deal with the spear-wielding Arabs – some money for their lives. With the whole crew back on board, the strongest swimmer swam to shore to pay the Arabs only to be gutted in full view of the crew. This was a grave foreshadowing of the fun that was ahead of them all.

The ship was in terrible condition, and there was no way to sail north to the Cape Verde Islands. Instead, then drifted south a couple hundred miles praying and hoping for rescue. Nine days later, out of food and water, they returned to shore in the middle of nowhere. (Today’s Western Sahara).

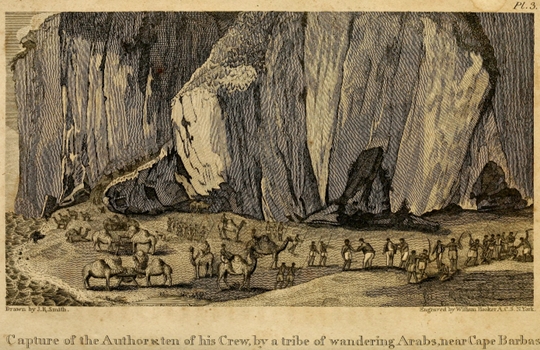

The crew climbed some high cliffs and wandered the desert for a while, before being intercepted by a bunch of guys on camels. Starving, sunburned beyond recognition, and near-death by dehydration, they offered themselves to the Arabs as slaves.

After some tribal infighting, the crew was split up and entered into servitude of the Arabs. Remember, this was in 1815 when slavery was still legal and rampant in America. So that’s a whole thing here – and a reason Abraham Lincoln cited this book as one of his most influential. Slavery is horrible no matter who is the master and who is the slave. Obviously.

(It Just occurred to me that two Connecticut authors shaped Lincoln’s resolve – Riley and of course Harriet Beecher Stowe, with her Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Pretty cool.)

The next weeks of Riley’s life are beyond horrible. The writing is a bit wordy and slow in places, but every so often you get gems like a comparison of the taste of camel’s urine to that of the author’s own. There’s also Riley’s fascination with women who sling their breasts back over their shoulders to feed their babies. Which is pretty efficient when they had things to do with their hands.

Being a slave is, in a word, terrible. Riley picked up enough of the language to communicate a bit. Enough to hoodwink a captor anyway. He convinced Sidi Hamet and his brother to buy him and his remaining mates and take him to the nearest city. There, he promised, he’d have a friend pay the brothers for their freedom.

Except he had no friend in western Africa and he was merely bluffing in a last ditch attempt to save his life. Riley wrote a letter to this non-existent “friend,” and they were off, on a several hundred mile slog north to what is now Essaouira on the Moroccan coast. So there they were, baking in the Saharan sun, near death, walking to their assured deaths.

The Americans weren’t the only ones about to die. Their Berber masters were starving and thirsty too, which meant the slaves were even hungrier and thirstier. All feared the strong chance of other tribes attacking them, as well as angry relatives out to settle a score. What a mess.

Captain Riley and his crew stranded on shore

Once on the outskirts of the city, Hamet the slavemaster took Riley’s note to the town’s consul – but fortuitously met a British merchant who acted as sort of a consul and was moved by Riley’s note. Moved enough to pay the several hundred dollars ransom for men he did not know. The savior turned out to be William Willshire who sort of devoted his life to saving enslaved white people in western Africa – which happened more often than you think.

Riley hung out with Willshire for a while and sent his rescued crew back to America. Riley tried to find and free his other crew who were enslaved by others – to some success. Later, he heard that his two masters were stoned to death out in the desert, most likely by other Arabs mad at them for freeing the Americans.

Riley and Willshire remained friends for life and were also business partners. Riley owed his life to the Englishman, and named his son after him, as well as the town of Willshire, Ohio. Which is a tiny town on the Indiana border in the middle of nowhere.

The book is a quick read despite some highly detailed accounts of the mundane. Riley’s descriptions of the Sahara and of Muslims and Arabs offers some fascinating insight into the times and locations. Not the best true-life adventure book I’ve ever read, but still definitely worth a read.

![]()

CTMQ’s List and Reviews of Connecticut Books

Leave a Reply