It’s Closed?! Neigh!

1st Company Governor’s Horse Guards Cavalry Museum, Avon

RIP, Late 1990’s (?)

Connecticut museum “visit” #424.

Avon, Connecticut: Voted one of the “preppiest” places in the United States in the 1980s best-seller “The Official Preppy Handbook.”

Avon: home of a school that looks as though it is from a Harry Potter movie.

And Avon, where just a couple minutes from the colonial charms of the classic New England town center of Avon, there exists one particular horse stable – one which used to contain a museum. One which has shed its museum past to join the heap of Defunct Museums that I’m fake visiting.

In fact, I’ve fake visited a few times. Most recently in the spring of 2019 after learning that the Guard does a sort of public practice on Thursday evenings. Upon arriving, I noticed no horses but there was a meeting going on in the main building – the building that used to house the museum.

I poked my head in and immediately determined that this was a recruitment operation that I wanted no part of. The meeting looked like any town hall meeting (read: boring) so I crept around looking for new picture opportunities, found none, and left.

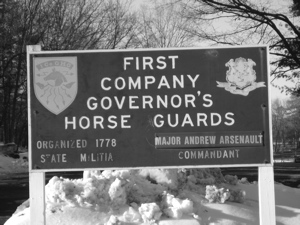

This place would get a page on CTMQ regardless of it ever having a museum or not. As you noticed on the picture of the sign above, Connecticut’s 1st Company Horse Guards is the oldest continuously mounted cavalry unit in the country! Right there in Avon!

While the museum is closed, the stable is most definitely not. There are many horses still cared for here – and for a very important reason: They are Connecticut’s First Company Governor’s Horse Guards! The Company is part of the organized militia of the State of Connecticut. Its mission is to serve the State whenever called upon by the proper officials and in whatever capacity is demanded. This may include the control of riots and other disorders, traffic and crowd control, and civil defense. The Company also upholds traditional customs and displays the pageantry of the U.S. Cavalry by participating in various celebrations throughout Connecticut and occasionally in other states.

Since I know nothing about the Calvary and less about horses, I’m a little bummed the museum no longer exists. During my very first visit, I caught the attention of one lady who waved and smiled, but nothing more. So I watched them herd the fine-looking beasts into their stables, looked around at what I could and finished my errands to hurry home and find out what this museum was all about. Below is a 1993 article from The New York Times about the museum.

So enjoy a very long article about a CT museum written by a real writer – and note the prediction of the museum’s closing towards the end.

![]()

Celebrating the History of Horse Soldiering

By ROBERT A. HAMILTON

Mention the cavalry, and most people picture the pony soldiers of the Old West, falling valiantly at Little Big Horn under the command of George Armstrong Custer. So where was the first United States cavalry unit based? Texas, maybe? Wyoming? Colorado?

Connecticut.

“Connecticut is actually the home of the United States Cavalry,” said Gary F. Brooks of East Hartford, curator of the Horse Cavalry Museum in Avon. Gen. George Washington, Mr. Brooks said, had told a Virginia friend that he could start the First Continental Light Dragoons, a force of armed mounted troopers that organized in December 1776. But about the same time Washington gave permission for the Second Continental Light Dragoons, which actually organized in Connecticut a few days earlier in the month.

That is just one of the things a visitor can learn at the cavalry museum, which its organizers bill as “the only one of its sort on the East Coast.” (There is a cavalry museum in Philadelphia, but it is open only by appointment. The Avon museum is open from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. Saturdays and noon to 4 P.M. Sundays in the Riverdale Shopping Complex, a group of restored farm buildings on Route 10 about a mile north of Route 44.)

Huh. How funny. Apparently I never thoroughly read this article until now, in the summer of 2019. Because this is the first I remember learning that the museum wasn’t at the stables, but a mile or two away at the shopping area. Oh well, here’s a picture of where it used to be.

Actually, this is one restaurant in the complex. I have no idea which building the museum was in.

Stirring military music blaring from a couple of discreetly placed speakers and a slightly musty smell of dried leather and rotting cloth greet visitors to the official museum of the First Company Governor’s Horse Guard, which was formed in 1778 and which is now the only state horse guard in the United States. The Army abolished the cavalry as a separate arm of the service in 1946, merging it with the armored forces, but the Horse Guard carries on the tradition.

The museum is a celebration of a long history of horse soldiering, with a special emphasis on Connecticut’s role.

Why is there such a strong association between the West and the cavalry?

“That’s TV,” Ralph L. Emerson Jr. of South Glastonbury scoffed as he leaned on one of the saddles from his collection that are on display at the museum. “Connecticut has a strong, strong horse tradition. Connecticut exported a large number of horses to the Caribbean during Colonial times. Connecticut currently has more horses per square mile than any other of the 50 states.

That was supposedly true in 1993. I wonder if it still is?

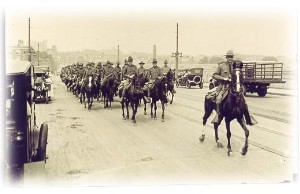

Photo from The Courant

“The oldest saddle company in the country is Smith Worthington, right here in Hartford,” Mr. Emerson said. “New Haven was a great center for carriage making. North & Judd, formerly in New Britain and now in Middlefield, was big for horse hardware. They had carloads of equipment go out from New Britain during the Civil War.”

The museum pays due homage to the horse. “When you’re cavalry, your horse is your best friend, your buddy, your pal,” Mr. Brooks said. “He carries you, and you talk with him, you groom him, you feed him carrots and take care of him when he’s sick. You have a certain bond with your animal that you can’t deny.”

It is that connection that makes the cavalry force unique, Mr. Brooks said.

Mr. Brooks, who joined the Horse Guard as a teen-ager in 1972, has advanced to first lieutenant and now has more continuous years in the guard than any other member.

The unit’s 50 men and women today volunteer 25,000 to 30,000 hours a year drilling and on duties like crowd control and search and rescue. They practice all the traditions of cavalry, including firing their 1903 Springfield rifles from horseback. Every Thursday the troop can be seen going through its paces at 232 West Avon Road in Avon.

… or not. Their website states that this still happens and I’ve read the same in updated guidebooks. But my one attempt came up empty.

Mr. Emerson, who has contributed heavily to the collection on display, was one of the last trainees in the regular Army cavalry. In 1944 he went through the training at Fort Riley in Kansas. On Victory Over Europe Day, he was stitching mule halters. “I was one of the last to have the privilege to go through the cavalry service,” Mr. Emerson recalls fondly.

The idea for the museum came about during the celebration of the Horse Guard’s bicentennial, when members were assembling artifacts for a display in the hotel where it was taking place, Mr. Brooks said. There were so many historical pieces that several members wondered if they could not mount a permanent exhibition, and Mr. Brooks became president and chairman of the soon-to-be museum.

A benefactor, who Mr. Brooks said would prefer to remain anonymous, paid for three years’ rent in the shopping center. With some display cases from D & L Stores, and financial backing from the Loctite Corporation and other corporations, the museum opened in October 1991.

The museum consists of two small rooms jammed with memorabilia stretching back to the Revolutionary War, most still carrying the faint smell of the horses that bore them as long as two centuries ago. And Mr. Brooks knows the tale behind every piece, like the device of wood and rusted iron that occupies an honored spot near the front of the museum.

“This is the plow General Israel Putnam was using more than 200 years ago in the field when an aide came up and told him the British were right down the road,” Mr. Brooks said. “He dropped that plow, he left that horse collar on his plow horse, and he escaped the British with this saddle,” he added, running his hands gently over a plain saddle of rotting, wrinkled, cracked leather. To get away, the 68-year-old Putnam rode his horse down steps so steep the British dared not follow, Mr. Brooks said.

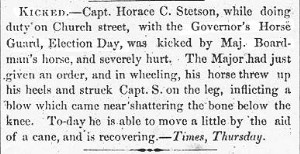

In addition to saddles from different eras, the museum has a complete collection of tack as well as the weaponry that horse soldiers have carried through the years, starting with the small pocket pistols, accurate to 20 feet, of 200 years ago. Posters show the different breeds of horses and the changes in uniforms of the cavalry over 200 years, military equitation training films from 1942, newspapers with accounts of the exploits of the Connecticut cavalry units and photographs of their service. There are even a couple of dull and dented bugles, the communications network of the cavalry.

“The cavalry would be nothing without bugles,” Mr. Brooks said. “It was said the horses knew the bugle calls better than the men. I heard that from a cavalry man who was born in 1889. There’s a call for everything — to get on the horse, to get off the horse, to increase the gait of the horse, to go right or go left,” Mr. Brooks said. “If you can think of it, there’s a call for it. Hundreds of calls for maneuvers.”

Mr. Brooks animatedly recounts the romantic tales of Connecticut’s cavalry, like the time Troop B Connecticut Cavalry was shipped to Niantic to merge with a Massachusetts unit. They were there two weeks when they saw their horses being taken away, and when they rushed to see what was going on they learned they would be a machine-gun battalion and would not need their mounts.

“These guys were devastated — they had joined the cavalry,” Mr. Brooks said. “So what they did is, they lined up in a gantlet, a stretcher went down between them, and they took off their campaign hats with the gold braid that signified they were cavalry, and they threw their hat cords on the stretcher and buried them, to symbolize that the cavalry had just died for them.” He shows off the museum’s solemn picture of the occasion, which was published in the local newspaper.

Mr. Brooks also can recount the details of the last United States Army cavalry charge. It was in the Philippines, just after the Japanese invasion, when American officers in charge of Filipino troops were ordered to do what they could to hold off the Japanese advance. On horseback, armed with pistols and sabers, they faced tanks and armored vehicles.

“Well, 727 saddled, lined and charged,” Mr. Brooks said. “They retreated with, say, 500. They regrouped and charged again, retreated and came back with about 300. They charged again. They regrouped, two colonels went to their tent and cracked open the last of the scotch, they passed it out, the guys drank the last of the booze, saddled up, and lined again with maybe 200 troopers, and charged again.

“They came back with 90 troopers — from 727,” Mr. Brooks said. “These people were dedicated to fighting for freedom, and they put their lives on the line for it. And that was the last cavalry charge. And the saddest thing was, the 90 horses that were left, they had to slaughter for their own food, and for a cavalryman to have to do that . . . .”

Displays in the museum are arranged chronologically, clockwise from the Revolutionary War to World War II and a wall devoted to the Horse Guard as a visitor leaves. The first display is a mannequin representing Thomas Young Seymour, the Second Continental Dragoon officer who escorted Gen. John Burgoyne to Boston after the British surrender at Saratoga.

“Burgoyne was so impressed with Seymour as an officer and a gentleman that he presented Seymour with his pistol holsters, his pistols and his leopard-skin cape,” Mr. Brooks said. “For a cavalry man to give up those items, it really meant something.”

Eisenhower Inauguration, Washington D. C., 1957

Also from the Revolutionary War is the collection of tack that belonged to Rufus Baker of Windham, chief of ordnance for the Continental Army, one of the only complete sets of its type in the world. “The Smithsonian wanted to get this equipment, they wanted to do a trade,” Mr. Brooks said. “But it stays here. This is part of Connecticut history. If we started trading, giving everything away, what we’re trying to uphold here would be gone.”

The Horse Guard used Baker’s tack to re-enact the delivery of the Declaration of Independence to Hartford in 1776, but the tradition ended in 1976. The leather is well stitched and still in good condition, a light sheen attesting to hours of patient cleaning. Other pieces from this era are dried and cracking. “Leather is a problem for any museum,” Mr. Emerson said. “When you have a relic piece, what you have to do is try to stabilize it. You’re never going to use it again, so you don’t have to soak it in oils and make it supple and pliable again.”

Some of the history of the cavalry is recounted in photographs and historical accounts. A copy of The Bismark Tribune Extra from the Dakota Territories offers the first account of the Custer massacre. “Massacre,” screams a large bold print headline. In smaller print, “General Custer and 261 men the victims,” and below it, “No officer or man of five companies left to tell the tale.” The story includes lurid headlines and lists the men who were killed.

From the Civil War, there is a McClellan saddle, named for Gen. George B. McClellan, its inventor. It has a well that allows ventilation of a horse’s back. In hot weather the trooper would empty his canteen into the well to cool the horse. The saddle itself is a thin layer of leather over unyielding wood. “It’s built for the comfort of a horse, and not the rider,” Mr. Brooks said.

If the horse is given its due, so is the mule. Four pack saddles are displayed — two British, one Swiss and one American. The pack saddle weighs 65 pounds, and troopers would put 300 more pounds on it. “The mule probably worked harder than anyone during the war,” Mr. Brooks said. “He was the lifeline. He carried their supplies, their ammunition, their food and everything, and when the guys took their five-minute smoke break they didn’t unpack the mule.”

Many of the exhibits come from families who are worried the role their fathers played in the horse soldiers will be lost to history. “A woman came in a year ago,” Mr. Brooks said. “She had her father’s uniform from World War I, his bridle, his medals and his saddle. He was in a New York outfit, served in France. Rather than have her kids throw it away when she passes on, she wanted her father remembered.”

Another display case contains the effects of Winthrop Hubbard Segar, who lived from 1906 to 1991 and who advanced from private to major commandant in his time in the Horse Guard. Mr. Brooks pays him the highest praise — “he was a real horseman” — and shows off his saber, medals and citations, and a picture of his horse, Congo.

A research library contains journals and books and other literature on the cavalry. In addition to two full guest registers with names from as far away as the Netherlands, there is a register for any serviceman to sign and a growing videotape library with oral histories from some old cavalrymen.

Mr. Brooks and Mr. Emerson encourage children to play with all but the most fragile exhibits. Youngsters can scramble over old saddles and try on helmets and ring the old field telephone with abandon. An All-Volunteer Staff

Mr. Brooks said his only concern was how to keep the museum going after the three-year lease runs out. “We could desperately use another benefactor,” he said. With an all-volunteer staff, operating expenses are held to just $7,000 a year, but the museum barely covers even that with donations. It sells tax-deductible memberships for as little as $15 a year, as well as T-shirts, horseshoes and other memorabilia, but it has resisted imposing an admission charge.

There you have it. A rare thorough examination of a museum I couldn’t and won’t visit. Although, the Avon Historical Society has commandeered a barn on the property and has tentative plans to restore it. Perhaps as a museum? Time will tell.

Also, the state owns the Horse Guard State Park Scenic Reserve right across route 167 from the Horse Guards. It’s a secret little spot to take a great hike.

![]()

1st Company Governor’s Horse Guards

CTMQ’s Firsts, Onlies, Oldests, Largests, Longests, Mosts, Smallests, & Bests

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Ival Kovner says

Ival Kovner says

April 15, 2009 at 8:18 pmWould like to know if the museum still exists and if I may be allowed to visit it. thank you, Ival

Diane Cordes says

Diane Cordes says

July 16, 2010 at 8:09 pmMy husband and I live on the property that once belonged to Israel Putnam (Brooklyn, CT). His first cabin site is in the middle of the field right behind our house. I’d be interested to know what will happen to his plow should no one care about it anymore – It would be awesome to bring it back “home.”

Patrice McClafferty says

Patrice McClafferty says

January 19, 2012 at 10:29 amI am looking for information about a former captain in the cavalry. His last name was Miller and I believe his first name was Larry. I believe he would be in his 80’s now. He showed me a video of his troop in a presidential parade. He also gave me a bridle that had a special medal on it that designated his status as captain. Can you help me find out further info about him or the bridle?

Steve says

Steve says

January 19, 2012 at 11:33 amUnfortunately, I can not. This website has nothing to do with the CT Horse Guard. In fact, I don’t even like horses.