A Really Old House in a Really Old Town

Windsor (Google Maps location)

December 2021

Windsor is one of “The Big Three” in Connecticut. Most readers of this website know what I mean by that, but if you don’t, “The Big Three” refers to Windsor, Hartford, Wethersfield – the first three towns formed and settled (by white people anyway) in the state. Lots and lots of history along the mighty Connecticut River here.

Yes, of course I just made up the term “The Big 3,” and – what’s that? That’s not even true? Deep River… yes, Deep River was number three and Hartford was actually fourth? Wow, you CTMQ readers are good. Yes, yes, New Haven was fifth. Let’s move on.

Windsor’s claim of being the first town in the state is a matter of pride that Wethersfield takes some issue with, but as far as the historical society here is concerned, the issue has long been settled. Like, since 1633 settled.

I entered the Windsor Historical Center Museum to secure a tour guide for the historic houses in the complex. After introductions and pleasantries about the lovely 60-degree December day and the impending end of civilized society, my tour guide for the Chaffee House began my visit with a nonchalant, “Windsor was settled in 1633 making it the oldest town in Connecticut no matter what Wethersfield says, welcome to the Dr. Hezekiah Chaffee House.” I liked that. Eliminating any room for debate before we even crossed the threshold. (I’ve written about the debate here.)

The WHS owns three museums to be toured. All three are bunched together on the Palisado Green on North Meadow Road, the first recognized road in the Connecticut Colony. It was the original road to Hartford. Hey man, this is the heart of Windsor! There’s super old Colonial era stuff everywhere you look!

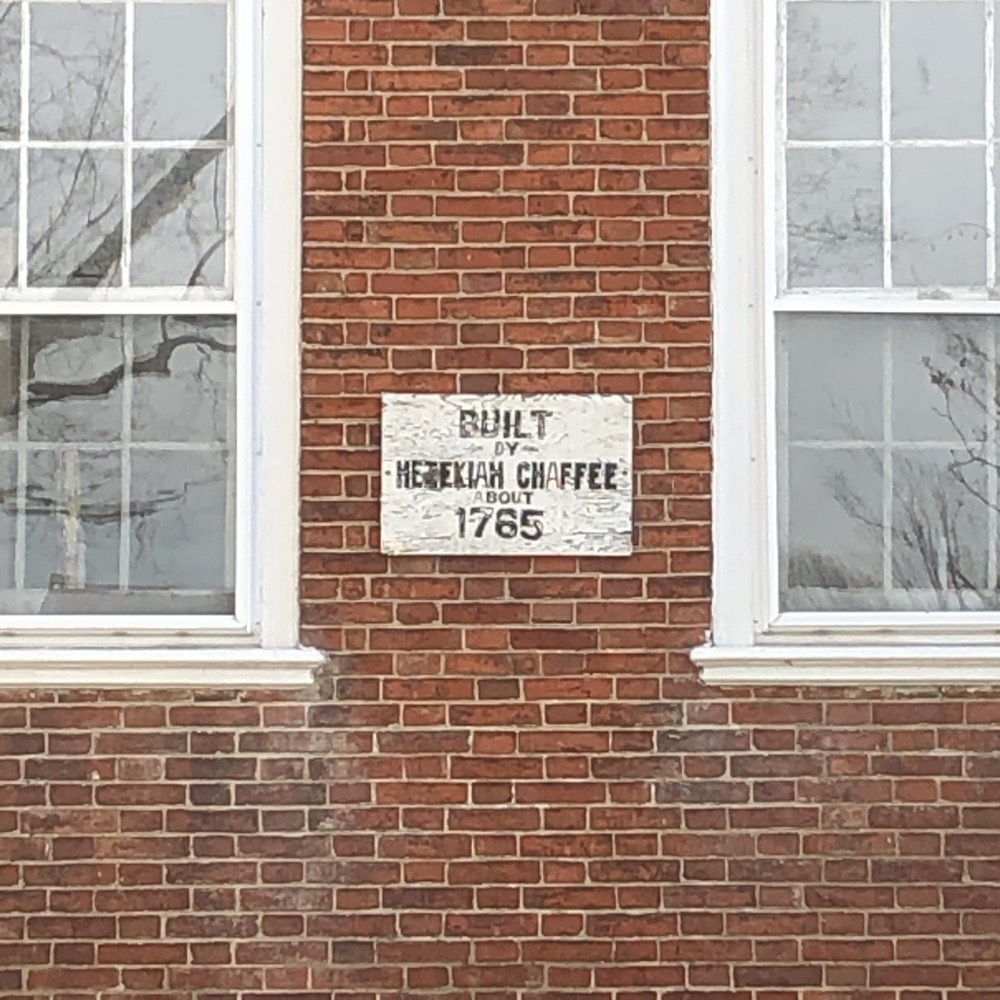

Dr. Chaffee purchased the land here and had the large Georgian colonial home built for him in 1766 or so. By the standards of the day, this house was huge. Records show that Dr. Chaffee outfitted it with all the top furniture and accoutrements of the time. Not Versailles level, but pretty darn fancy for the American Revolutionary Period for sure.

High chests, desks with bookcases, silk-on-silk embroidered scenes, and fine dishware. Dr. Chaffee’s medical office was built as an addition in 1800 where he and his doctor son plied their trade. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

During my visit, and perhaps in perpetuity, only the ground floor is open for tours. The South Parlor, the office, a bedchamber, the kitchen, and the north parlor which is a temporary exhibit space for things wholly unrelated to the Chaffee family.

WHS has set up the tour experience in an interesting way. Several placards throughout have two columns; one for the wealthy white doctor experience and one for their slaves’ completely different experience. Yes, Dr. Chaffee had slaves. Several, actually. In 1774, half of all the ministers, lawyers, and public officials in Connecticut owned slaves, and a third of all doctors.

Heck, Connecticut had the largest number of slaves in New England at the time. Slavery wasn’t officially abolished in the state until 1848, but there were several positive steps before then, freeing many black and indigenous people here through various ways and means.

My guide seemed slightly uncomfortable with the fact that ministers were some of the longest holdouts regarding slavery. I was offered a Pollyanna revisionist idea that perhaps these slave-owning ministers were kind to their slaves and owned them to protect them from other, meaner slave owners. Now, I’m sure this was the case for some preacher, somewhere, at some point in time, but… I’m not buying that.

I tend to believe the fact that the Bible was used as a pro-slavery guidebook. It started in Genesis 9:18-27 and continues throughout, most notably Apostle Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians, 6:5-7. That’s the whole “Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart…” bit.

So yes, Dr. Chaffee had slaves. Four, actually. Sarah, Betty, Jack, and Nancy. I was assured that the good doctor’s slaves were well-regarded and treated as fairly as… a piece of human property could be treated. But hey, someone needed to keep this big house clean and efficiently running as apparently the Chaffees themselves could not.

A placard here explains how the Chaffees used to relax and play board games in their parlor while “nurturing their family.” On the flipside, we learned that slave families were broken up; husbands and wives and children all living in different towns, owned by different families. One of Chaffee’s slaves left a young daughter in Hartford, and the Chaffee’s most famous slave, Nancy Toney, was bought and brought here when she was only 11.

Onto the medical office where there’s a collection of historic medical instruments and a bunch of fake pills and scales and stuff for young visitors to play with. Here you can open drawers in the apothecary chest and desk, page through medical texts, and look through reproduction receipts made from Dr. Chaffee’s actual practice.

Oh, about that practice. Dr. Chaffee wasn’t an actual licensed doctor or anything, as that didn’t really exist in the 1770’s. The mere fact that he was educated and could read his medical texts qualified him for the role. I guess he was halfway decent at it to be able to accumulate the wealth that he did. But here’s the craziest thing I learned here: there was a black “doctor” here as well. Dr. Primus Manumit.

Manumit was enslaved by another doctor in town and learned the trade from him. He traveled with him to treat the servants in the homes he visited. There is thought that Dr. Chaffee provided the same training for Jack Pell, one of his slaves. I guess that’s pretty cool, if a little weird. We moved on to the colonial kitchen. (By the way, to “manumit” is to free a slave.)

Here is where the slave women spent their days, dawn to night, literally slaving away over a hot stove. (When they weren’t emptying chamber pots, darning socks, doing laundry, or sweeping the joint.) They slept in attics and little shacks near the home. There were three women working here… actually one was only 4 when she was brought on to do some work in the home.

Fish and peas. My son Calvin would die.

The records on the Chaffee female slaves are convoluted, and several seemed to come and go over the years. But one remained constant: Nancy Toney. She was given as a wedding gift to Hezekiah Jr.’s bride. (Man, that’s just an insane sentence.) She was one of the last slaves in Connecticut and has become sort of a symbol of the whole system. She has a nice gravestone across the street at the Palisado Cemetery, a stop along the Connecticut Freedom Trail. Osbert Loomis painted a portrait of her, facing the artist – an apparently very rare thing during those times.

She lived with the Chaffee family for decades, and apparently became sort of like family to them. At least that’s what we’re told today. Nancy Toney’s life had been shaped by enslavement in the Chaffee family. Slavery prevented her from gaining education, additional job experience, and from sustaining relationships within her own birth family. So, you know, being happy with her life is a very relative thing.

By the mid-1800’s, the Chaffee family in Windsor petered out and the home was ultimately used as the Chaffee School for girls. At some point, the girls here joined the boys at the Loomis Institute down the road which is now the pricey Loomis-Chaffee boarding school. The town of Windsor took possession of the house and the museum was created in the 1990’s.

Over that decade, the historical society began collecting period furniture, as none of the Chaffee possessions were available. (My guide suggested that one bedside table might have been from the Chaffee family, but no one is sure.) The Connecticut Historical Society and one charitable family began donating and lending furniture pieces to outfit the historic house museum. These include a Connecticut Valley high chest and a desk-bookcase, some Connecticut Valley chairs, a Pembroke table, two candle stands, some porcelain, a sampler, and other textile pieces.

The results of which can be seen there today. The little bedroom is outfitted quite nicely – though it would have been upstairs of course, for as long as the Chaffees could navigate stairs.

The temporary exhibit on display was all about the local West Indian population who first came to Windsor to work the tobacco fields. Many have stayed, of course, and the fairly large display went into great detail about their immigration, work, and culture. (Of course, there’s some parallel between the black slaves of the 18th-century and the difficult working conditions in the tobacco fields for white farm owners, but there’s no need to get into that.) I didn’t spend too much time reading the signs here, as I had the Strong-Howard House Museum to get to across the street and – shhhh – I was visiting during my lunch break.

I applaud the Windsor Historical Society for allowing and encouraging open discussion on the slave ownership of the museum’s namesake. They’ve given voice to the voiceless and the portrait of Nancy Toney that hangs in the kitchen is impactful. The placards juxtaposing the Chaffee family’s life and that of their slaves is jarring and important. My guide was interesting and fun and laughed at my jokes; which is all I ask for. Well done, Windsor, well done.

Built for him, not by him. And apparently one or two years later.

Windsor Historical Society

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Leave a Reply