In CAES You Didn’t Know…

CT Agricultural Experimental Station

New Haven

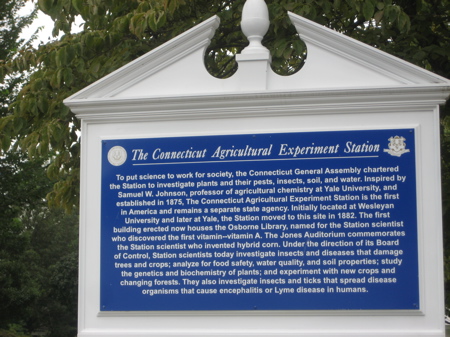

Some CTMQ readers may roll their eyes at this one, but you really shouldn’t. To put science to work for society, the Connecticut Agricultural General Assembly chartered The Station to investigate plant and their pests, insects, soil, and water. Inspired by Samuel W. Johnson, professor of agricultural chemistry at Yale University, and established in 1875. The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station is the first in the America.

And it has been important ever since. I “visited” the station during an all-out New Haven CTMQ day, but never went inside. (It is, after all, a National Historic Landmark – CTMQ Report here) and their farm in Hamden is so cool, I treated their annual open house as a museum, here.

Since there are two pages on the CAES (and another on their experimental Lockwood Farm), I wanted to make this one different. So I’m going to give you an excellent article on the station, From the Yale Scientific Magazine.

Enjoy:

Amino Acids, Alleles, & Antibodies

The Work of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station

By Véronique Greenwood

“The Station is a child of Yale University,” explained John Anderson, director of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station.

His metaphor is apt; this public laboratory — the first of its kind in the nation — has indeed been intertwined with Yale since its birth in 1875. The brainchild of Yale professor Samuel W. Johnson, CAES has grown to prominence with many groundbreaking discoveries and remains near enough to campus — just a half-hour walk — that students and faculty are able to continually interact with the lab. What Johnson, a Yale agricultural chemistry professor at the time, envisioned was a government-funded laboratory near a university which would test soils, analyze fertilizers, and work to develop a systematic, applicable study of the science of farming for the public good.

Although the Station was first opened at Wesleyan University for funding reasons, by 1877 it had relocated to the corner of Grove and Prospect streets in New Haven, under the auspices of the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale. Since then, it has undergone another move to its current location above Science Hill and expanded its research substantially, but its motto remains “Putting Science to Work for Society.”

Public Service Through ScienceServices at CAES are free, and any consumer wanting to know the composition of his soil, fertilizer, cattle food, seeds, or whether an insect or plant carries a disease has only to fill out a form and agree that all results will be made available for public use. By 1877, the Station had already saved farmers $50,000 in fertilizer bills by exposing frauds and calculating the “true worth” of analyzed fertilizers.

Early annual reports describe the muckraking of CAES scientists who had analyzed adulterated food: in 1900, for example, the baking soda of the Southern Soda Works was found to be more than 25 percent pulverized talc and tremolite, a common paper filler appearing as a mass of jagged splinters under the microscope. Long before the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the Station hoped to discourage the sale of adulterated foods by the dissemination of the brand names whose products had been analyzed and found wanting.

The Station was also instrumental in preventing the spread of crop diseases. For example, when samples of wood sent in by a fruit farmer were found to be infested with San Jose scale, a sucking insect which produces round blemishes on fruit and bark and can kill a tree if left uncontrolled, CAES scientists organized a quarantine and treatment system. The Station also documented the breeding places of malarial mosquitoes and directed efforts to control the emergence of gypsy moths, whose larvae feed on crops.

With a trust fund established by William Lockwood in 1894, the Station was able to start its own research farm, Lockwood Farm, in Hamden, CT. At the new facililty, scientists set up studies involving crop nutrition with fruit trees, and the fungicide juglone, which is much more toxic than the previously popular copper oxide, was discovered.

Yale and the StationIn many endeavors over the years, Yale and CAES scientists collaborated on important breakthroughs. In 1909, Thomas B. Osborne, a chemist at the Station and Yale Research Chemist, and Yale’s Lafayette Mendel set up experiments to observe the nutritive value of specific isolated seed proteins in the diets of rats. The rats were fed a mixture of pure protein, salt, starch, and lard, but unless whole milk powder was added to their diet, they sickened and died.

[Note: Lafayette Mendell’s house is also a National Historic Landmark – CTMQ Report here]

De-proteined whole milk powder — simply lactose and minerals — was then used as the rats’ main food. A specific combination of proteins was added to the powder so that their effects could be observed. Osborne and Mendel observed that certain proteins, including gliadin in wheat and zein in corn, could not support a rat’s nutritive needs alone, because these proteins did not provide crucial amino acids which the body cannot manufacture itself. Diets without the amino acid lysine, for instance, caused the rat’s growth to be stunted. As soon as it was fed the missing amino acid, however, its growth continued. Osborne and Mendel hypothesized that this was because while some amino acids served in the maintenance of the body, others were needed to cause new growth, and these could not be produced by the rat itself. These results further supported their conclusion that some amino acids must necessarily be obtained from food — an idea which has since become a central concept in the study of nutrition.

Nevertheless, some rats continued to decline on the de-proteined milk diet. Osborne and Mendel tried adding butter to the mix, and the rats dramatically recovered “as if a substance exerting a marked influence upon growth were present in butter.” Further work indicated that a nutrient of some sort was present in fats, without which development was mediocre and, specifically, susceptibility to eye disease was increased.

Through their study of this mysterious substance, Osborne and Mendel, along with E.V. McCollum and Marguerite Davis at University of Wisconsin, were among the first to produce the idea of “vitamin theory” — that is, some diseases are caused not by germs, but rather, simply by a deficiency in certain essential nutrients, called “vitamins.” Mendel and Osborne then demonstrated that chickens could be raised healthily on an artificial diet containing that first vitamin observed by Osborne and Mendel — Vitamin A. This procedure is now the basis for modern industrial chicken farming.

Double-Crossed Corn

While Osborne and Mendel were working with rats, chickens, and biochemistry, agricultural science was being manipulated on a higher level by Donald F. Jones. Arriving at the station in 1914 at the age of 25, the geneticist took up the extant corn-breeding program and intended to produce a vigorous, high-yield hybrid. Jones carried normal corn-breeding methods one step further beyond the normal single-cross — the breeding of two inbred lines — to the double-cross, producing a super hybrid combining the best characteristics of four inbred lines.

Jones’ work received significant attention, and, in fact, the future vice president of the United States, Henry A. Wallace, took an interest in Jones’ work and started the first hybrid seed company, Hi-Bred, in 1926. Jones continued his work at CAES through the 1950s, developing male sterility and restorer genes in corn to make hybridizing easier.

The implementation of Jones’ methods resulted in wildly increased corn production, and while much has changed in the hybrid corn industry since Jones’ day, corn yields from hybrids continue to explode today. According to Robert Evenson, Yale professor of economics and a former corn farmer, yields have increased from 57 bushels an acre in 1957 to about 160 bushels an acre today, with corn growing competitions in the Midwest producing 300 bushels an acre. Almost 100 percent of all corn planted in the U.S. today is hybrid corn.

Diagnosing Diseases

More recently, research at the Station has led to improved methods for testing for Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases. In the 1980s, CAES scientists, notably Louis Magnarelli and John Anderson, vice director and director respectively, were instrumental in determining which tests for antibodies in infected serum produced the most reliable positive for Lyme disease.

You can (and should) continue reading the article here.

The state is fortunate to have the partnership of Yale here and vice-versa. Actually, we ALL are fortunate for this. I think I’ll get my soil tested this spring… Just because I can.

![]()

CT Agricultural Experimental Station

Leave a Reply