Full Gas

Stafford (Google Maps location)

October 2017

I do not know if Donald Passardi still opens his private museum to visitors.

Information on this place is very hard to come by these days – not that it was ever easy. Heck, I’ve never been sure what the name of this place is. I’ve seen it as Gasoline Alley Automotive Museum and I’ve seen it as Donald Passardi’s Ford Museum.

Whichever is correct, just know that this is a private museum on Mr. Passardi’s property that if open, is only open very rarely via appointment… if even at all anymore. But if it is when you read this, and you are interested in automotive history, you’ll want to figure out how to see the priceless collection.

I received an invite from a reader to some sort of “locals only” open house in 2017. I believe it was done in partnership with the Stafford Historical Society Museum. Like, only museum members were invited. I am not a local nor a SHS member, but hey… I should get a few perks like this, right?

Right. I don’t know if Passardi lives in Stafford because of its proximity to the Stafford Motor Speedway, but that’s a nice happenstance if not.

Regardless of its accessibility or proximity to this or that, Passardi has amassed an amazing collection. I’ve said often that I don’t collect anything, but am always fascinated by people who devote their lives to doing so. Many of these types of collectors aren’t millionaires either. It takes passion, dedication, persistence, and decades of effort.

In Passardi’s case, he worked the overnight shift at the Stop & Shop in Glastonbury and spent his days collecting automobile relics. Rather than be squeezed out of his home, he built a 4,800-square-foot museum next door, exclusively for his collection.

Passardi began collecting all things Ford decades ago – he purchased a 1930 Ford Model A pickup truck when he was 15 – but was focused on selling them off to make a small profit. Then one day he decided to start keeping these Ford treasures for himself. I guess he realized that the things he was seeking wouldn’t be around forever – especially the one-of-a-kind items. And so the collection grew and grew. It filled his garage and more.

Over the years, Passardi became pretty well known to Ford collectors and he eventually opened his “museum” to anyone to visit, free of charge. My own conversation with Passardi was very short as there were dozens of others there during my visit, and I had Damian with me.

The museum is hard to miss from the road. There’s a vintage gas station pump in front of a white garage. (There were also a bunch of llamas and emus right next to the property which I guess is normal in Stafford.)

He’s been host to visitors from all over the world. They come to see things like the 1930s-era antifreeze display, the ’40s- era Gulf motor oil cans – still full – the ornate gas pumps with glass globes, and the fleet of restored cars – including a 1946 Ford Sportsman, one of just 743 manufactured. This is an astonishing collection.

In fact, Passardi has things that no one else has. He has developed a relationship with the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Dearborn, Michigan because they have come calling for items that they are missing.

Some of the more unique items in his collection: The 1934 Chicago Century of Progress Ford Rotunda architect model that he bought in Michigan many years ago and was featured in the V-8 Times magazine; a Henry Ford wax figure which was purchased at an auction when the Gaslight Village wax museum in Lake George, NY closed; a “globe” trophy from a 1937 Ford sales winner; a baseball marked “1933 Exposition V8” and signed by Henry Ford along with photo of Henry signing baseballs.

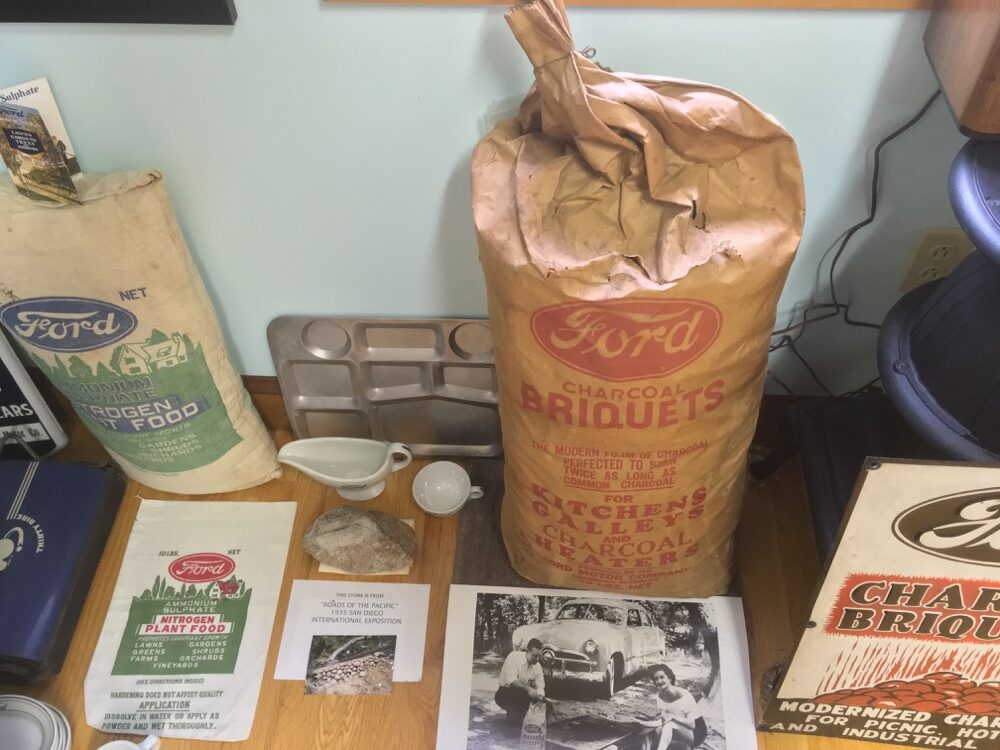

If you need another example of why collectors are a bit odd – actually, there are dozens of items here that prove this, but this one stood out to me – Passardi has some Ford charcoal briquets and barbecue stuff. This is one of the most prized possessions here. Not the actual antique cars, but some old charcoal.

I do appreciate that the collection extends beyond car stuff. Ford got involved in all sorts of business ventures, and Passardi is here to prove it. Ford produced his own tomato juice from the thousands of acres of farmland he owned. Since he couldn’t market the juice on his own, he sold his business to the Ford Motor Co. Passardi has several of the original tomato juice bottles in display cases. Ford also produced fertilizer, and experimented with gasoline made out of soybeans in the late 1930s and 40s, according to the museum.

But back to the charcoal, as there’s more to it than just Ford’s name on the bag. It turns out that Ford himself was involved in the creation of the briquette. I encourage you to read this story from the New York Times which explains how Ford, along with a Michigan real estate agent named Edward G. Kingsford, Thomas Edison, and tire magnate Harvey Firestone went on a camping trip during which they discussed all the wood used for the millions of Model T’s Ford was selling. Ford hated the wasted wood so they worked with a guy in Oregon to use the sawdust and stumps to make briquettes.

Ford marketed them to be sold at dealerships or families to take on their trips in their Model T’s, and well, okay, I get why there’s a bag of old charcoal in Stafford now.

And one of the things Passardi wishes he had? A boxed piece of cake from Henry and Clara’s 50th Anniversary. He had a chance to buy one some years ago but thought it must be a fake, until he saw some on display somewhere. So odd to me.

There are things here like an actual copy of the Detroit Times from the day Henry Ford died in 1947. That makes more sense. And a rare 1946 Ford Sportsman convertible with side panels made of maple and mahogany? Totally fair.

Original political advertisements promoting Ford’s little-known bid for the presidency? Oh yeah. China used in the cafeterias of Ford factories? Okay, getting weird again. Passardi’s extensive collection includes more than 10,000 original items, most dating between 1903 and 1953.

It goes without saying that Passardi has spent a good deal of his money on his collection. I’m sure his numbers fluctuate, but I believe he had about 15 antique Ford automobiles when I visited.

One thing I learned is that Passardi is obsessive about cataloging his collection. He does the research and tries to find corroborating evidence that what he has is original. (For example, he found pictures of people eating off his Ford cafeteria china to go with his Ford china set.) I very much appreciate that and can relate to that bit of his obsession.

The rarest items here, I think, are those related to Ford’s short-lived political career. In 1918, Ford ran for the U.S. Senate, but lost. He also ran for president in 1924, but dropped out after winning the Michigan primary to support Woodrow Wilson.

Passardi has original advertisements, campaign pins, and other Ford presidential memorabilia. He even has a sign from the 1920s that reads “Wilson needs Henry Ford.”

Passardi has badges from almost every Ford plant in the country. Let’s see… what else… Ford pedal cars, trophies given out to employees in the early 1940s, ladies compacts from the 1930s, gear shift knobs sold at expositions, salt and pepper shakers in the shape of the Rotunda building, Ford perfume bottles, stamps, printer blocks commemorative plates, and countless other items.

His rarest automobile is a 1946 Ford Sportsman, a wood-sided convertible. The car has power windows, a button on the floor to switch the radio, and a fire extinguisher which apparently makes it rarer. It cost about $1,600, which was twice the cost of a typical Ford at the time.

Also in the garage is a Ford neon light from 1932, which still works. Everywhere I turned there was some other Ford thing. I apologize for not knowing much about cars, as I’m sure a different intrepid Connecticut museum cataloger would be able to write 3,000 words about the cars alone.

Oh well, I’ll leave you with this tidbit: Passardi drives a Ford Crown Victoria. That’s all I’ve got.

![]()

Leave a Reply