Aloha! Aloha.

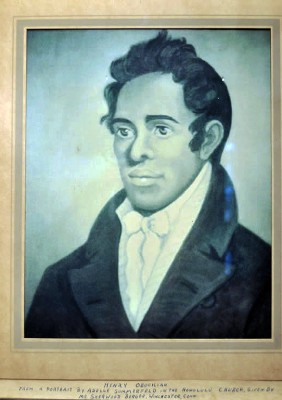

Henry (Opukaha’ia) Obookiah’s Cenotaph, Cornwall

February 25, 2012

This page also serves as a book review of Sarah Vowell’s “Unfamiliar Fishes.”

[Cenotaph: a sepulchral monument erected in memory of a deceased person whose body is buried elsewhere.]

Six years into this whole CTMQ thing, I still come across stuff that surprises and excites me. The mere fact that something in a cemetery qualifies for that is surprising in itself. Longtime readers know that I have never cared too much for cemeteries, but over the course of writing this site I’ve come to realize there are some really cool stories in them all around the state.

I’m a big fan of Sarah Vowell and her books. If you read this website, you’ll enjoy them too, as she’s the much better professional writer-with-a-budget version of me. (She’s also a great “Daily Show” guest as well.) One of her books, The Wordy Shipmates, focuses on the Puritans and their ways – and features our Thomas Hooker and a lot of stuff about colonial Connecticut. Takeaway: Thomas Hooker was a bit religiously insane.

But when I picked up her newest book (at the time I picked it up anyway) called Unfamiliar Fishes, I had absolutely no expectation to learn anything about Connecticut. After all, the book is about the long and somewhat sordid history of Hawaii’s annexation. It’s an absolutely fascinating history of something most Americans know nothing about.

And yes, Connecticut played a rather important role in Hawaii’s path to statehood. To this day, there are remnants of those early efforts in both Cornwall and Farmington. To relay the entire story of Henry Obookiah would be taxing on me and too much for you to read. So I’ll try to condense the story; a story which is filled with several names and places that still hold great importance in Connecticut history. (Now that I’m done putting this page together, I realize I didn’t do a very good job of condensing.)

All four of us were out in Sharon for some CTMQ Adventuring and I stopped by the cemetery on our way home. It was cold; very cold. But I found the gravesite and now I have this long story to tell.

First, the story in historical text form from the Coffee Times:

Few details are known about Opukaha’ia’s early life, though most historians believe he was born about 1792 in Ka’u at Ninole near Punalu’u on the Big Island. From Opukaha’ia’s own account, written much later, both of his parents were killed during a war made after the old king died, to see who should be the greatest among them. Opukaha’ia, who is thought to have been ten or 12 at the time, fled from the rampaging warriors carrying his infant brother on his back. A spear thrown by one of the soldiers found its mark, and the baby brother was killed. Opukaha’ia survived, but the same soldier who had killed his parents became his guardian for the next year and a half.

That war, by the way, is a wholly separate and fascinating tale that Vowell relates. And this story is crazy already, right? All these Hawaiian words that follow are defined in Vowell’s book. Like, for instance, the kapu system was the ancient Polynesian social caste system of sorts.

During this time, Opukaha’ia discovered that a kahuna at a nearby temple was his uncle, so he was allowed to go to live with his grandmother and this uncle. While he was visiting an aunt in a nearby village, soldiers came to take her prisoner for some infraction of the kapu system, but Opukaha’ia once again survived by escaping through a hole in the grass hale (house). While he watched, a soldier threw this aunt over a pali (cliff) to her death. Opukaha’ia returned to the home of his uncle at Napo’opo’o where he was schooled in the rituals of the priesthood, so eventually he could take his uncle’s place as a kahuna at Hiki’au Heiau, the same heiau where Captain James Cook had met his demise two decades earlier in 1779.

In his memoir Opukaha’ia wrote, …I began to think about leaving that country to go to some other part of the world… probably I may find some comfort, more than to live there without father or mother.

As soon as the sailing ship Triumph anchored in Kealakekua Bay, he went on board. Captain Brintnall invited another young Hawaiian boy named Hopo’o, along with Opukaha’ia, who spoke no English, to stay for dinner and to spend the night on board ship. The next day, it was arranged that the two boys would sail with the ship. Opukaha’ia was 16 years old.

The sailors called Opukaha’ia Henry, and spelled his last name the way they pronounced it, Obookiah. During the next two years, Opukaha’ia sailed on the Triumph to the Seal Islands (situated between Alaska and Japan), back to Hawai’i, to Macao, and around the Cape of Good Hope, landing in New York in 1809. On board he developed a friendship with a Christian sailor named Russell Hubbard, who began teaching Opukaha’ia how to read and write, often using the bible as a primer.

When the ship was sold in New York, a merchant invited Opukaha’ia and Hopo’o home for dinner. The boys were astounded at the number of rooms in the house and by the fact that cooking was done indoors, but they found it even harder to believe that women sat at the same table and ate with men, and the gods did not harm them. In Hawai’i, the old kapu (taboos) were still observed; women could not eat with men.

There you go, more info on kapu. And now we’re about to get to the good Connecticut stuff.

Opukaha’ia continued his studies while he lived with Captain Brintnall and his family in New Haven, Connecticut, but it wasn’t until he met a man named Edwin Dwight, a student at Yale College who became his teacher, that he made real progress. Certain English sounds proved especially difficult-r was often used in place of l for example. Years later, in the writings of early missionaries, words such as Honolulu and Kilauea were written Honoruru and Kirauea.

With his new reading skills, came a new view of religion. As Opukaha’ia began to believe in a Christian God, he compared Hawaiians’ worship of gods represented by wooden idols. He said, “Hawai’i gods. They wood-burn. Me go home, put ’em in fire, burn ’em up. They no see, no hear, no anything.” On a more profound note he added, “We make them (idols). Our God-he make us.” His new faith was further ingrained when he lived for a time with the family of the president of Yale College, who, as he put it, was a praying family morning and evening.

During the spring, summer and early fall, Opukaha’ia moved from farm to farm around Torringford and Litchfield, Connecticut and Hollis, New Hampshire, planting, harvesting and always studying. The church communities of Litchfield encouraged him, and by 1814, in addition to speaking publicly, he began to translate the bible into Hawaiian and to start compiling a dictionary/grammar book in the Hawaiian language.

People in Connecticut had begun to talk of sending missionaries to foreign countries-Hawai’i, in particular, as several young native Christians (like Opukaha’ia) would be able to pave the way. Opukaha’ia continued to fill his inquisitive mind with knowledge at Yale College. Not only did he undertake Latin, Hebrew, geometry and geography, he improved his English by writing the story of his life in a book called Memoirs of Henry Obookiah. By 1815, he had finished writing his personal history and had begun to keep a diary that detailed his feelings about his faith.

By 1817, a dozen students, six of them Hawaiians, were training at the Foreign Mission School to become missionaries to teach the Christian faith to people around the world.

But the following year, Opukaha’ia fell sick. A physician, Doctor Calhoun, quickly diagnosed his illness as typhus fever. Though treatment seemed at first to help, Opukaha’ia continued to get weaker and weaker, and he died on February 17, 1818. Attendants noted a heavenly smile on his face. He was 26 years old. Among his last words were Alloah o e-translated in his memoirs as My love be with you.

The little book about his life was printed and circulated after his death. It inspired 14 missionaries to volunteer to carry his message to the Sandwich Islands. Of those who sailed on the Thaddeus on October 23, 1819, only Samuel Ruggles had met Opukaha’ia face-to-face. The work Opukaha’ia did on translating the bible and recording the Hawaiian language in a grammar/dictionary/spelling book, paved the way for the missionaries to print the first Hawaiian primer and bible stories in the Hawaiian language.

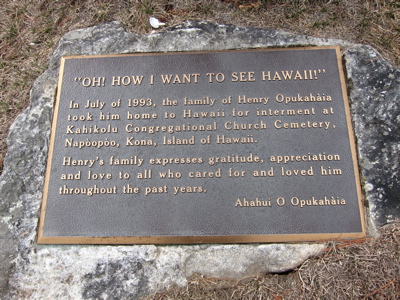

Opukaha’ia’s body was buried in a hillside cemetery in Cornwall, Connecticut, where it remained for 185 years. In 1993, a group of his descendants, spearheaded by Deborah Lee, brought the body home to the Big Island. The remains were reinterred at Kahikolu Cemetery in Napo’opo’o, near Kealakekua Bay in South Kona. A plaque marks the spot, cared for by Ka ‘Ohe Ola Hou, a group formed to perpetuate the achievements of the devout young man who is believed to be the first Hawaiian convert to Christianity-a young man whose zeal was the reason the first missionaries came to Hawai’i in 1820.

That’s a lot to absorb, I know. And depending on your mindset, you may think he’s super important to Hawaiian culture or the worst thing to ever happen to Hawaiian culture. Me? All he did was trade one set of myths for another; simply pulled by the culture he was immersed in. No biggie. (Though one must wonder why such a pious guy had to die such a tragic death.)

So that’s the general history of Obookiah. Vowell helps us get more into the Connecticut details. Some Yale guys and some Andover guys came up with the idea that missionaries should be sent to Asia. This brainstorm inspired the formation of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, the group that would eventually sponsor the missionaries to the Sandwich Islands (aka, Hawaii).

That’s when a man named Mills brought Obookiah to his father’s Connecticut farm and then took him along to Andover Theological Seminary outside of Boston, an institution of such pious gloom townspeople called it “Brismstone Hill.”

…Mills had designs on Henry from the get-go, writing a letter after they met at Yale “proposing that Obookiah be setn back to reclaim his own countrymen, and that a Christian mission accompany him.”

Mills, Timothy Dwight, and other men of faith who founded the ABCFM would use the empirical data and maps of European explorers like Cook and La Perouse to fan out evangelists across the Pacific to spread the fear of God as far and wide as Cook’s men ha spread the clap.

…

Meanwhile, New England’s commercial ships began returning from China with more boys of Obookiah’s ilk they’d picked up along the way. In 1816, godly high-rollers in the ABCFM, including Dwight and his protégé, the Reverand Lyman Beecher, met at New Haven to plan a school for “heathen youths” to be built in Cornwall, a tiny hamlet in the Litchfield Hills.

… The founders chose this nowheresville, rather than a city like Boston or New Haven, so as to hinder the foreign students from “acquiring the tastes and habits of city life.” Cornwall was not then, nor is it now, known for its theaters. I passed through it a couple of centuries after the school was built, and from what I could tell the closest thing to entertainment was the town blood drive.

So then the kid (with 11 others) learned all about Jesus and did their thing that you already read about. Lyman Beecher himself gave the sermon at his funeral. (He was, of course, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s father.)

His cenotaph says:

In Memory of Henry Obookiah a native of Owhyee. His arrival in this country gave rise to the Foreign mission school, of which he was a worthy member. He was once an Idolator, and was designed for a Pagan Priest; but by the grace of God and by the prayers and instructions of pious friends, he became a Christian. He was eminent for piety and missionary Zeal. When almost prepared to return to his native Isle to preach the Gospel, God took to himself. In his last sickness, he wept and prayed for Owyhee, but was submissive. He died without fear with a heavenly smile on his countenance and glory in his soul. Feb. 17, 1818; aged 26.

After his remains were taken to Hawaii, Vowell continues…

…It’s hard to beat the view from his new resting place. But the Litchfield Hills have their charms, especially in the spring, when the countryside is all lilting greenery with the occasional jonquil in bloom.

One April, I had to do a reading in western Massachusetts so on the way I stopped in Cornwall to see Obookiah’s original tomb. There in the village cemetery among the monuments for Yankees with names like Martha, Harriet, and Luther, Obookiah’s weathered marker still stands on a gentle slope near the road. The inscription is hard to make out. The centuries have blackened the lettering and the surface of the stone is covered in little trinkets and offerings – corroding coins, strings of shells, a broken coffee mug from Kamehameha Middle School in Kapalama. I’m guessing the Kamehameha mug from Oahu is probably just a memento left there by a well-meaning Hawaiian sixth-grader unaware that Obookiah came to New England in the first place because some of Kamehameha’s soldiers stabbed his mom and dad.

Now you know why I love Sarah Vowell. Anyway, as you see in one of my terrible pictures, that broken mug still survives after at least a couple winters.

And speaking of winters, Vowell describes later New England missionaries swarming the islands, coming equipped with early pre-fab housing. The typical colonial construction methods, it turned out, weren’t exactly ideal for Hawaiian heat. I don’t know why, but I found that funny. They probably prayed for cooler weather for a year before deciding to adapt.

And that’s about it. Though it seems that there is a plaque at the long gone Foreign Mission School in Cornwall (now a church) that reads: “Between 1817 and 1826 it trained young men of many races to act as Christian missionaries among their peoples.”

Note to self: Get a picture of that someday.

2020 Update: It is now a National Historic Landmark!

![]()

CTMQ’s List and Reviews of Connecticut Books

Leave a Reply