Other than Farmington and Hartford, New Haven is Ground Zero for the Freedom Trail. Yale seems to have fed the progressive spirit, but it’s also where the Amistad is moored (when its moored) and where the famous Amistad slave trial took place.

Let’s rock.

![]()

1. The People’s Center

37 Howe Street

Hi. It’s 2012 me. I just poked around and found a much longer explanation of what the People’s Center is (on the Freedom Trail website) so here you are:

Built in 1851, The Peoples Center was purchased by a group of mainly Jewish, immigrant workers who fervently believed that their new homeland should be a model of peace and social and econimic justice. The tradesmen and artisans who had grown up speaking Polish, Yiddish and Russian, envisioned for their families a center of social and cultural life. They contributed 25 cents per week to the Center.

The Peoples Center’s doors were always open. During the 1930’s, it housed the Unity Players, the first black/white intergrated drama organization in New Haven. The New Haven Redwings, the city’s first black/white basketball team, also originated there. The first city celebration of International Women’s Day took place here.

As the Great Depression closed in upon the nation, The Peoples Center gave its rooms over to the unemployed to organize for jobs, to keep their homes, and to work for the unemployment insurance and social security laws that many now take for granted. Organizing the Connecticut CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) began here. During this period Woody Guthrie sang a benefit concert for the Peoples Center. The very first anti-fascist, anti-nazi meetings in the city were convened at 37 Howe Street. Volunteers for the Abraham Lincoln Brigades were sent off from the Peoples Center to fight for the Republic in Spain’s Civil War, and the survivors welcomed back.

During the 1940’s, the chart of the Peoples Center initiated activities included rallies against lynchings, organizing to end segregated baseball leagues, and campaigns to integrate the jobs of bus driver and railroad worker.

To fulfill the need of workers to advance their education, New Haven’s first evening college was conceived at 37 Howe Street. It became the evening division of New Haven State Teachers College on nearby Legion Avenue, now Southern Connecticut State University.

The Cold War marked another era for 37 Howe Street. A new climate pervaded the community: Progressives and whoever refused to join assaults on them were branded traitors. Threats on the life of Paul Robeson (his house is part of the Freedom Trail too), rallied organizers from the People’s Center to send a bus full of supporters to protect him and his September 1949 concert at Peekskill, New York.

Throughout the 1950’s and ’60’s activities at the Center turned largely defensive, sheltering the gains that working people had achieved in the previous two decades and guarding labor and other progressive leaders from attacks by Senator McCarthy and his followers. Despite these hardships, local coordination for Martin Luther King’s 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington and later in the decade, support of a fair trail for members of the Black Panther Party coalesced at 37 Howe.

By the early 1970’s McCarthyism and its most devastating scars had become history, yet activities at the People’s Center barely recovered. In 1973, to revitalize the Howe Street structure and preserve its half-century tradition Progressive Education and Research Associates bought the site.

For the first time in many years New Haven again had a place to celebrate May Day, recalling our great – grandparents’ seminal struggle for the 8-hour workday; annual African American History Month celebrations were established; weekly potluck suppers brought together Peoples Center neighbors with activists from a variety of causes. The John and Milada Marsalka Library was opened and dedicated to the extraordinary efforts of two long-time, remarkably energetic New Haven progrssives.

In the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s the Peoples Center provided affordable (often free) space to working men and women organizing for better wages, for health care, for weekends off, for paid vacations; machinists at Winchester (now U.S. Repeating Arms), hospital workers at Yale-New Haven, health care providers at the Jewish Home, New Haven teachers, Yale, Harco, Circuit-Wise workers, – just as it had made room in decades past for Connecticut tobacco workers, clothing workers, and Sargent Company employees.

Most recently, the 140 year-old 37 Howe Street opened its doors as a Drop In Center for homeless individuals who had nowhere to go to escape the cold. Managed by We The People, the Center kept them warm while they played checkers or chess, watched television, took literacy classes, met with medical personnel and social service providers, read, or slept.

The high volume traffic, low rents and absence of a paid building superintendent left the Peoples Center desperately needing rehabilitation. Recognizing the significance of saving this historic institution, the community rallied.

With an outpouring of supportive letters, critical testimony at public hearings and backing from sympathetic New Haven Alderpersons, The People’s Center won Community Development Block Grants for renovation. To these were added many generous individual donations, volunteer professional services and donations of supplies, labor from the Innovative Homeless Program, Living Wages Jobs Program, Youthbuild, and special help form the Haymarket People’s Fund and Architecture Theatre Prometheus.

After a two-year break, the new New Haven Peoples Center is again providing for the people’s needs. With continued support of its friends, the Center history will extend into the future, advancing labor and peace and justice issues, guaranteeing space and shelter, and inspiring us with the great good work done within its walls.

…

Wow. I had no idea about any of that when I had Hoang snap the picture as we drove by on our way to lunch one day.

![]()

2. Trowbridge Square Historic District

(City Point Area)

I love New Haven, but I have to admit that I’ve never been to any of the more blighted areas of the city. This year (2010) is on pace to break all murder records for the city as they are now up to 15 I think. I’ve done absolutely zero research into this, but I’m guessing at least a couple were in the area around Trowbridge Square Park. Which is obviously a tragedy.

The noted abolitionist Simeon Jocelyn developed Trowbridge Square in the 1830s in partnership with architect and builder Isaac Thompson. The area was established for New Haven’s low-income working-class population and was meant to be a model egalitarian residential community populated by African Americans and whites. Restrictive covenants on sale of alcohol and racial discrimination sought to improve the residents’ quality of life. A school for African Americans was built on Carlisle Street to further encourage them to move to the area, and by 1845 African Americans made up almost 58 percent of the Trowbridge Square population. The district is on the National Register of Historic Places.

There is a nice sign in the park which contains a little more detail. I deftly avoided an angry (apparently) drunk (apparently) homeless guy to get this picture, so you better appreciate it:

![]()

3. Edward A. Bouchet Burial Monument

Evergreen Cemetery 92 Winthrop Avenue

As I navigated the littered streets of southwestern New Haven, I realized that I never looked up where this guy’s grave was. On top of that, Evergreen Cemetery appeared closed, which of course made no sense. However, the Winhrop Avenue entrances were closed, most likely because the neighborhood on that side of the property is, um, crap.

So I drove all the way around the cemetery to Ella Grasso Blvd and entered the open main entrance. Realizing I had no idea where to go (and this place is an absolute maze of roads), I sheepishly entered the office and thankfully found a map of notables buried there. Most notably, Dr. Edward Bouchet.

With a major in physics, Dr. Edward A. Bouchet was the first African American to obtain a doctorate in any discipline and the first to be inducted into Phi Beta Kappa. He was the sixth person awarded a doctoral degree in the Western Hemisphere. As a youngster he attended the Artisan Street Colored School and graduated summa cum laude in 1874 from Yale University. The monument to Dr. Bouchet in Evergreen Cemetery was unveiled in October 1998.

I found his handsome new gravestone (with more impressive plaudits) and was about to go about my business until I saw the brochure had another site stating, “Freedom Trail marker.” Hm. I found the tall Connecticut State Civil War Volunteer’s Memorial monument and noted the little Freedom Trail plaque. This isn’t mentioned at all in the Freedom Trail literature though. But I’ll take it! Bonus Freedom Trail coverage!

![]()

4. Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church,

217 Dixwell Avenue

Slowly but surely I’m hitting all the New Haven historical landmarks. There are three within earshot of each other on Dixwell Avenue, but on the day I stopped by the Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church, I didn’t bother with the other two. (There was a whole wedding party in front of the other church and a gathering of dubious individuals in front of the other house. I just didn’t feel compelled to snap pictures of either.) No worries, I’ll be in New Haven a million more times to take care of them.

Architecturally, this is certainly not your typical New England church. But somehow the blocky modern look is certainly at home in New Haven with several iconic brutalist structures around town. Anyway, in 1820, Simeon Jocelyn and 24 former slaves organized the African Ecclesiastical Society. As a white abolitionist, Mr. Jocelyn demonstrated the passion necessary to lead this congregation. In the beginning, the Society would meet at various homes throughout New Haven until establishing itself on Temple Street. In 1829 the African Ecclesiastical Society was formally established as a Congregational Church. Mr. Jocelyn served as the first minister.

Even liberal abolitionists kept the brothers down. Sigh. Its first African American minister was James W.C. Pennington, and from 1841 to 1858 Amos Gerry Beman was the pastor. Both were well-known African American leaders in the United States. During Beman’s ministry the growth of the church made it necessary to relocate the congregation to a new building. By 1896 the church moved to Dixwell Avenue, where it developed numerous community programs under the Reverend Edward Goin. It remained at that location on Dixwell Avenue until 1967. In that year, under the leadership of Reverend Dr. Edwin R. Edmonds, the church moved to its current location at 217 Dixwell Avenue.

![]()

5. Goffe Street School (Prince Hall Masonic Temple)

106 Goffe Street

Nothing extraordinary about this building.

The former Goffe Street School was built in 1864 to provide a much-needed facility for African-American children. It closed ten years later after Connecticut ended racially segregated education, and many of its former students attended predominantly white public schools. Subsequently used by a number of organizations working with the African American community, the building was purchased in 1929 by the Grand Lodge of Prince Hall Masons of Connecticut. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places and known as Widow’s Son Lodge #1.

I just poked around looking for some interesting stuff on the CT Freemasons and found nothing. Well, other than maybe the fact that Benedict Arnold was a Freemason in New Haven.

This building stands directly across the street from the Dixwell Fire Station, which is part of the Urban Museum of Modern Architecture, which I suppose is mildly interesting to every 745th person to read this. (CTMQ Visit here)

I did find some info on the old Goffe Street School: AfroAmericans, nationwide, not only saw a need to organize churches and businesses due to segregation, they knew that it had become important to organize schools and organizations during the 1860’s1890’s. Miss Sally Wilson was the first black teacher in New Haven. One of her students, Edward Bouchet (see two entries above), was the first black to receive a four year degree from Yale University. During 1864, the Goffe Street Special School was built for black children at the corners of Goffe and Sperry Streets by a Board of Trustees.

The black children had been offered very little education in Trowbridge Square on Carlisle Street of the Hill Section during the 1840’s. In 1874, the school on Goffe Street closed, because the AfroAmerican children began attending public schools that had been only for the white children previously. The Board of Trustees kept the school, and it was available for committees/organizations to use in the AfroAmerican Community. Hence, St. Luke’s Church used the building for a parish hall after World War I.

![]()

6. Hannah Gray Home

235 Dixwell Avenue

This stop along the Freedom Trail in New Haven was a bit of a pain in the butt to find. For all the right reasons.

You see, I think the address has slightly changed – or at least isn’t exactly visible from Dixwell Avenue. But that’s because the Hannah Gray Home has recently undergone a very impressive facelift and somehow it looks (to me) like the address has shifted. No matter, I figured the building I was looking at simply had to be the right place, snapped a picture and went home.

Okay, it wasn’t quite that easy… For this stretch of Dixwell Ave is not exactly family friendly. While there are three Freedom Trail spots all within earshot of each other here, that hasn’t been enough to clean up the area to make it touristy. Shocking, I know. I parked my car at some slightly sketchy strip mall and walked out onto Dixwell Ave.

This immediately caught the attention of a nearby cop who left his parking spot and drove by me… Twice. This, in turn, made me feel strange about taking pictures of the Hannah Gray Home and the Varick AME Zion church across the street. But I did it – for YOU – the faithful Freedom Trail followers. I would guess most suburban looking white guys walking around looking suspicious are there for something other than taking pictures of churches (the Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church is only half a block away).

So what is this large newly sided house?

Hannah Gray was a laundress and seamstress who used part of her income to promote the antislavery movement and support her church. Through her will, Gray donated her house at 158 Dixwell Avenue (no longer extant) to be used as a refuge for “indigent Colored Females.” Because her will did not include funding to administer the home, it was almost sold for delinquent taxes in 1904. It was saved by the Women’s Twentieth Century Club, an organization of African American women which took responsibility for maintaining it. The present Hannah Gray Home at 235 Dixwell Avenue, acquired in 1911 and accommodating more residents than the original structure, continues in operation in accordance with its founder’s goals. The building is included in the Winchester Repeating Arms Company National Register Historic District.

Unfortunately, the Home as it was intended again fell into financial woe. The Home was operated in its intended capacity at the current site until 1996 when it was forced to close for financial and administrative reasons. The facility reopened in January 2010 with a slightly different mission – to serve the elderly poor in the immediate Dixwell Avenue area.

![]()

7. Varick A.M.E. Zion Church,

242 Dixwell Avenue

Directly across the street from the Hannah Gray Home and a stone’s throw from the Dixwell Ave Congregational Church is this old gem.

Varick African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church was organized in 1818 when more than 30 African Americans left the Methodist Church to form their own congregation. In 1820 it became officially affiliated with the Zionist church movement of James Varick, who helped lead a separation from white Methodism because African American preachers were not permitted to be ordained. By 1841 the church had a building on Broad Street, but it relocated in 1872 to Foote Street. In 1908 the present building was constructed, and it was here that Booker T. Washington made his last public speech before his death in 1915. The church is included in the Winchester Repeating Arms Company National Register Historic District.

That’s pretty darn interesting, huh? The Booker T. Washington bit? I thought so.

The woman in the picture though didn’t. In fact, as I walked in front of the church scoping it out and reading the little sign in front which says pretty much what the above paragraph says, she stared me down and gave me the stink eye like you wouldn’t believe. It was very uncomfortable. Add to it the fact that the cop (mentioned in the Hannah Gray Home blurb above) was circling me and yeah, I was looking forward to getting back in the car.

No telling what that woman, the sketchy kid across the Ave and the cop thought I was up to all that time.

![]()

8. William Lanson Site

Lock and Canal Streets

Hoang and I were driving from lunch to a random museum one day in October 2011 and I was sure to drive by this site – which isn’t really much of a site at all. Especially since it’s under construction. But oh! It sure used to be something. What?

This:

African American William Lanson’s (1776-1851) life straddled the late 18th and mid-19th centuries. During his life, the self taught master builder, contractor and property owner of what is now Wooster Square earned accolades from New Haven’s Timothy Dwight, President of Yale University, and James Hillhouse, politician, anti-slavery activist and superintendent of the Farmington Canal. Lanson provided strength and leadership to New Haven’s African American community and was elected Black Governor in 1825. Maligned and nearly forgotten, the words of Isaiah Lanson, William’s son, capture his role in shaping Connecticut history and New Haven’s infrastructure. In 1842, Isaiah wrote:

“Mr. Lanson is an old inhabitant; he has worked in this town about thirty-eight years; he built nearly all the East Haven Bridge and the steamboat wharf, with his own hands; and also long wharf, which he built, when there was no way of getting to the pier without going in boats. Mr. Lanson’s earning on that wharf amounted to about $25,000; there is also the basin wharf, with two walls, six feet thick, and one thousand feet long.”

![]()

[Note: I visited these next two trail spots on a freezing cold Saturday in January 2013. My wife wanted me to go get something at Ikea. Fine. But darn it, don’t you think for a second I’m not going to pick up two Freedom Trail spots that have been nagging me for years while I do your bidding! I play tough.]

9. Constance Baker Motley House

8 Garden Street

Finally! I’ve had this (and the next stop of the Freedom Trail in New Haven) on my to-do list for years. I’ve driven within a few blocks of this house probably ten times without nabbing it. The streets around Garden are wacky one ways and it always seemed like one of my kids was acting up or I was in a rush or it was dark or something.

It had reached the point of the absurd.

But here it is, in all its glory – I had no idea this woman passed away fairly recently. That makes me sad.

Constance Baker Motley (1921-2005) was a trailblazing lawyer in the forefront of many major civil rights cases throughout the mid-20th century. After graduating from Columbia Law School in 1946, Motley was hired by Thurgood Marshall to work as a law clerk for the NAACP. In 1950, Motley wrote the draft complaint for the landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which ended segregation in schools. Over the following decade, she successfully argued numerous other civil rights cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, becoming the first African American woman to do so. In 1964, Motley was the first woman elected to the New York State Senate and, in 1965, the first woman to become president of the Borough of Manhattan. In addition to her accomplishments as an attorney, Motley was the first African American woman to be appointed a federal judge of the United States, in 1966. She became a chief judge in 1982 and served the Southern District of New York as a senior judge for the rest of her life. Motley made outstanding strides in the movement for social justice and equality during the 20th century and, in 1998, she was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. Motley’s childhood home is privately owned and not open to the public.

Wow. Just wow. The things I’ve learned doing this website… and now I’ve been to her childhood home. (Seriously, I wish I knew all this before I drove by. I’d have at least nodded in appreciation or something.)

![]()

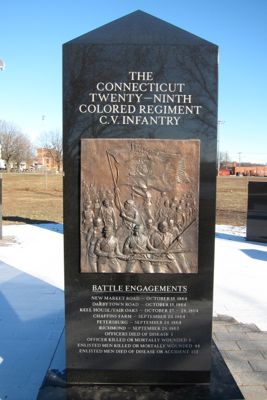

10. 29th Colored Regiment Monument

Criscuolo Park, Chapel and James Streets

Like the previous trail stop, I have thought about picking up this trail stop at least 5 times in the past. Probably more like 10. I did make an attempt in the fall of 2012 with my family and wound up contemplating anonymous sex or buying crack on a dead end street bordering Crisculo Park.

I did neither (this time) and poked around the park; marveling at its strange location. Amazingly, I did not see the rather huge monument to the 29th Colored Regiment. I’m not smart.

I did notice this store with a rather unique claim to fame:

I also enjoyed the park’s namesake’s memorial marker, which says simply, “John Paul Criscuolo Park – A Unique Man.”

Honestly, I would be happy with that. “A unique man.” I really like that.

Not finding the site, I gave up and went on to Ikea with my wife and boys. A couple months later I was sent to New Haven again on a mission to buy some chairs and a rug. In the meantime I had checked my man Jerry Dougherty’s site to see what I missed.

Wow. It’s huge! It even shows up clearly on Google Satellite. But now I’d make it right.

The monument is very well done and really, really classy. The environs, however, could be a bit better. Maybe someday.

Criscuolo Park in 1863 was a very different place than it is today. In the fall of that year, in the midst of the Civil War, more than 900 black recruits for the 29th Regiment of Connecticut Volunteers mustered and trained to fight for their country on those grounds. One year earlier, the governor opposed enlisting black troops, but as the war wore on, it became difficult to meet enlistment demands. As the first all-black regiment in Connecticut, the troops of the 29th endured racism and discrimination. They received lower pay than white troops and were often ordered to the back of the corps. Still, the Regiment fought valiantly in several engagements in Virginia and the men of the 29th were the first infantry units to enter Richmond after it was abandoned by the Confederate Army. A few days later, they witnessed history when President Lincoln visited the city and the bloody war was over. Dedicated in 2008, the monument at Criscuolo Park commemorates the soldiers of the Connecticut 29th Colored Regiment C.V. Infantry. The memorial was designed by sculptor Ed Hamilton, who also created the Amistad Memorial in downtown New Haven.

The 29th has a great website with tons more info about their storied history. You should go read it.

![]()

CTMQ’s Concept of Freedom Trail page

CTMQ’s Freedom Trail page

Lauren says

Lauren says

February 7, 2013 at 4:12 amAre you serious with your bio for number 2? You didn’t research the city prior to your visit? This is an Ivy League town in a wealthy state…What do you expect? The have-nots are resorting to violence as their home is usurped by Yale so they can better kiss PFizer’s ass.

New Haven- Phenomenal pizza and high murder rates. So be it!

Steve says

Steve says

February 7, 2013 at 10:15 amGood point. I shall study the annual murder rates of every town I visit henceforth.