Adding to the Canon

Salisbury

When I began this website in 2006, the Salisbury Cannon Museum’s website was exactly the same as it is in 2022. The same pictures, the same URL, and the same note that it is “currently closed.” I don’t know about you, but “currently closed” offers hope that it will reopen someday.

So I waited 16 years.

And it hasn’t reopened and I think we can agree that it won’t ever reopen. Some of the artifacts, I assume, have been moved to the Salisbury Association’s history museum, but even with that being the case, we still lost a pretty cool little museum.

Actually, we lost two pretty cool little museums at this same spot. The two northwesternmost museums in Connecticut! Gone! Yes, as you surely remember, the Holley-Williams House Museum was located here as well.

Today? Today it appears to be a large private residence right on Route 44, Salisbury’s main drag. And the town itself is quite different than it was 300 years ago. It has become a somewhat remote chic-chic enclave for New Yorkers to get a taste of the Berkshires a little closer to the city. Back in the day, it was a hugely important center of iron producing.

More specifically, the area was a cannon producer during the American Revolution. And the Cannon Museum was located right next to the historic site of Connecticut’s first iron blast furnace that was originally built by Ethan Allen and Samuel Forbes in 1762.

Whoa. Ethan Allen!

Yes, Ethan Allen

Ethan Allen was a Connecticut boy. Born in Litchfield, raised in Cornwall.

After rich iron ore deposits were discovered at Ore Hill in 1731, forges were established here. Gee, you’d think the name “Ore Hill” would have tipped off the Revolutionaries, eh? Winky face emoji.

In 1762, Ethan Allen joined in partnership with others and built the first blast furnace in the area, known as the Salisbury Furnace. Initially, the furnace produced basic iron goods for early colonists, such as tools, cooking utensils, and stoves. During the struggle for independence, the Salisbury Furnace produced cannon and other armaments of war and became known as the Arsenal of the Revolution.

Did you know that “cannon” is the plural of “cannon?” It is. Or used to be. Actually, it still is but since we no longer make or use cannon, we just don’t use the proper plural much anymore.

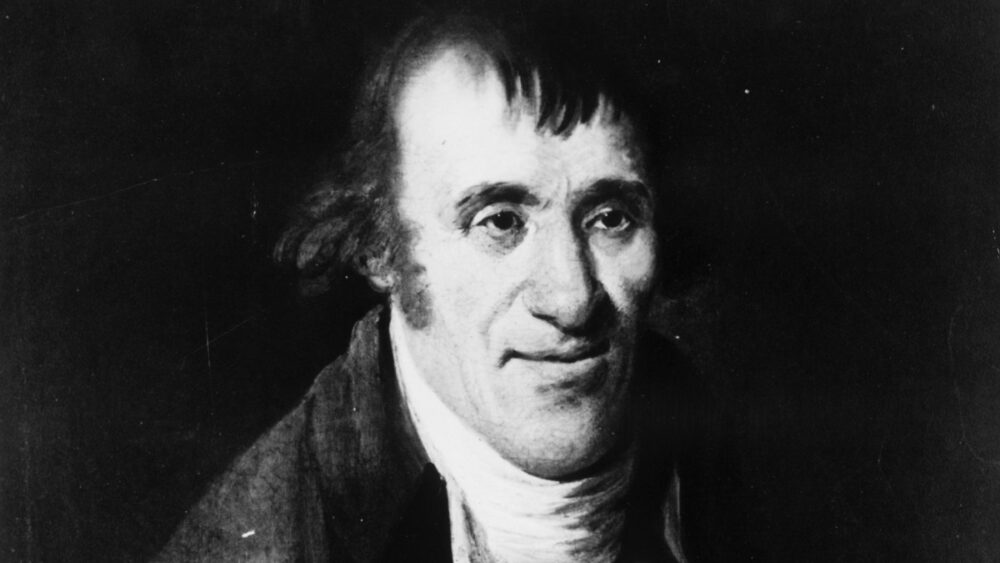

Photo from the Cannon Museum website

Ethan Allen worked his parent’s farm before going to study in Salisbury. When his father died, he returned to Cornwall to help raise his seven brothers and sisters and maintain the farm. He was called for a brief military stint at Fort William Henry at Lake George, which was under threat of attack by the French and their Indian allies in the French and Indian War. He returned to the family farm for a little while before striking out on his own in 1761 – back over to Salisbury.

When Ethan was settled there, he learned of the rich lode of iron ore that had been found there, an entire hill of almost pure hematite, virtually free of impurities. Ore Hill had been divided into eight parts, each owned by different proprietors. One share was owned by two brothers in Canaan, where they operated two iron forges, Samuel and Elisha Forbes.

Ethan realized that there was a great opportunity awaiting the person who could build a charcoal blast furnace in Salisbury to melt the iron ore so it could be cast into useful products and into iron bars to be hammered in the forges. Everything that was needed for a blast furnace was right there in Salisbury: a large lake fed by springs with a steady outflow of water that could operate a water wheel to produce compressed air; a large supply of limestone that could be dug out of the hills at Lime Rock, midway between Cornwall and Salisbury; hills covered with hardwood trees which could be harvested to make charcoal; and finally, Ore Hill itself, with its fabulous lode of high quality iron ore.

Ethan fortunately met a man with a similar desire, Paul Hazeltine, who with his father and brothers operated several iron works in Eastern Massachusetts. Paul’s father, John, on hearing of the potential in Salisbury, committed himself to build a blast furnace if the necessary property and mineral rights could be obtained. Ethan promptly took care of this, working with the Forbes brothers, and in January 1762 the four men entered into a partnership to construct the furnace. For his contribution in making the arrangements and his continuing tie to the operation, Ethan received a one-eighth interest in the furnace.

Photo from the Cannon Museum website

Soon the furnace was in full operation, with a large crew of local workmen under Allen’s direction, producing potash kettles, pig iron and other needed products. The furnace continued in operation for over eighty years, until the year 1844, when it was torn down to make way for a factory producing pocket knives – the basis of the aforementioned Holley-Williams House Museum. But it was that period in the 1700’s that made this forge and Salisbury famous.

A section of one of the pieces of pig iron produced by Ethan Allen in 1764 was discovered buried not far from the furnace site, and was on display in the Salisbury Cannon Museum. I have no idea where that is now.

In 1765, Ethan Allen sold his interest in the Salisbury Furnace and embarked on various business ventures in Massachusetts and Vermont. Acquisition of Vermont land soon led to his becoming commander of the voluntary militia – the “Green Mountain Boys” – created to fight off rival land claimants coming over from New York. Those battles were fierce, but not as fierce as the American Revolution.

Photo from the Cannon Museum website

Within a month of the first shots fired at Lexington and Concord, Ethan Allen, together with Colonel Joshua Porter and other locals, planned, financed, and led the attack on Fort Ticonderoga. The capture of the fort was the first offensive victory for the colonists. It also secured a strategic passageway to and from Canada.

At the time hostilities broke out, the Salisbury Furnace was owned by an Englishman, Richard Smith. He returned to England in December 1775 and remained there for the duration of the war. Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull directed that the furnace be confiscated and made ready for production of cannon. On May 27, 1776, the first cannon was produced. By war’s end, the Salisbury Furnace had turned out some 850 cannon, estimated to have been three-fourths of all those made in the colonies, as well as ammunition and other armaments.

Read that last paragraph again. That’s pretty incredible and certainly worthy of a dedicated Cannon Museum in Salisbury. I understand that such museums aren’t high on many people’s itineraries, but this is a pretty important place in the history of the United States. There is the Beckley Furnace site over in North Canaan a few miles east on Route 44 that’s worth checking out, and there is (was? at least on paper) an Iron Heritage Trail if you’d like to learn everything about the industry.

The museum was in the garage and not this lovely main house

Leave a Reply