Damn! No, really… Damn!

Saville Dam & Barkhamsted Center, Barkhamsted

September 2024

The Saville Dam is surely a top 10 Connecticut beauty spot. If it didn’t require a walk in order to get the perfect shot, I’m sure it would be top 3. As it is, you still have to wait in line on weekend days in October in order to get photos of the dam’s center tower.

Photo by Justin Coleman

Some of you are now like, “ohhhh, that’s Saville Dam. I had no idea what it’s called.”

And those of you who knew, likely didn’t know it’s named in honor of its chief engineer, Caleb Mills Saville, a guy who had helped design the Panama Canal.

And those of you who knew that it was named in honor of Caleb Mills Saville, likely haven’t been inside and underneath the dang thing.

And those of you who have been inside and underneath the dang thing, surely don’t have an awesome website about everything cool in Connecticut, so your story is now my story, accuracy be damned.

Which brings me to my title… my story of going inside and underneath the dang thing can only be presented with words. The MDC has security concerns about photographs of the dam’s innerworkings so although one of the MDC officials let us take all the pictures we wanted, the other was none to pleased. I was later told no pictures were to be made public.

Which is a shame, because getting inside Saville Dam is… awesome. Awesome like “awesome” in the dictionary. This structure is truly an engineering marvel… never mind the communities its construction displaced – a story we’ll get to in a bit. So let’s get going.

The Dam Tour

Tours of the dam occur infrequently and are coordinated between the MDC and the Barkhamsted Historical Society and as well as the Farmington River Watershed Association. I cannot tell you the cadence of these tours, but can tell you that the pandemic stopped them for a couple years. I can tell you that they are very infrequent and that they will cost you some money, but that it will be worth it. I can only speak to the Historical Society’s tour, which was excellent.

I had been asked to give a talk to the Society about my CTMQ adventures and when asked what I’d want for an honorarium, I replied, “I just want to go on the dam tour.” I was told they had one scheduled several months in the future and I immediately took that day off from work and circled the date in thick red marker on my calendar. I wasn’t going to miss this for anything.

We gathered at a parking lot in Peoples State Forest and boarded a school bus for our morning together. I was effusively greeted by the wonderful Noreen Watson who seemed as excited to have me there as I was to be there.

I was not excited to be on my first school bus ride since… sixth grade? 1986?

I do not fit comfortably on school buses

Fortunately the bus ride – generously donated by LeGeyt Bus Company, a name that will crop up later on this page – wasn’t too long. We arrived at the dam’s lower gate house at which point the Society’s Paul Hart gave us a talk.

Yes, “us.” A good 40 people showed up for this tour, and apparently that’s the norm. And that’s great! (Granted, those 40 people were almost all retirees and in fact, I enjoyed overhearing a conversation on the way over about girdles and cataract surgery. These are my people, even if I’m not one of them… yet.)

Paul gave us a 20 minute history lesson on the dam; why it was built, when it was built, and how it was built. It was a million times more compelling than you may think.

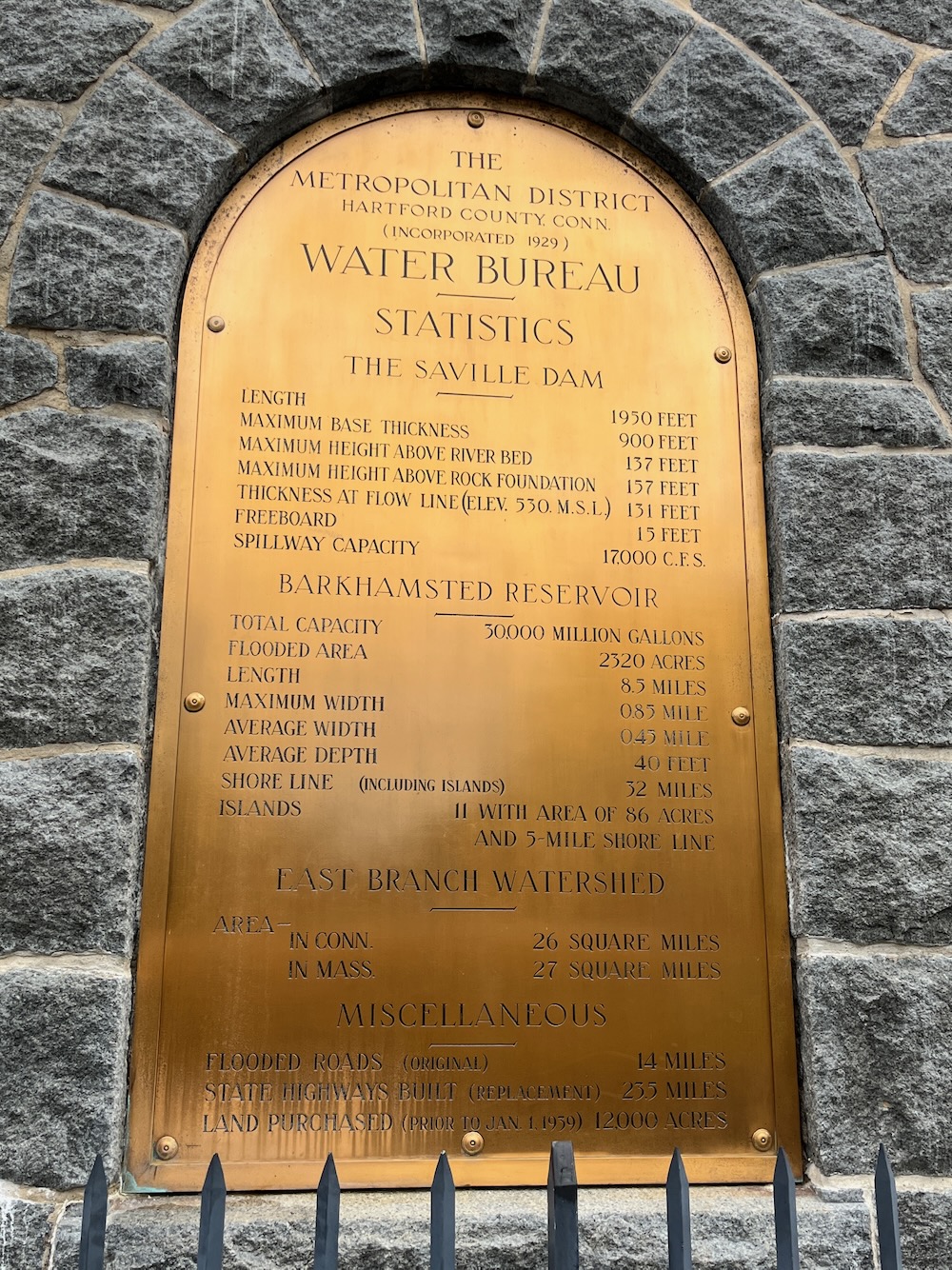

The Saville Dam is an earthen embankment dam with masonry work on the eastern branch of the Farmington River. The dam is in Barkhamsted, the resulting reservoir reaches north through Hartland almost to Massachusetts, with the compensating reservoir (Lake McDonough) reaching south into New Hartford. The dam is 135 feet tall and 1,950 feet long. It created the Barkhamsted Reservoir which has a volume of 36.8 billion gallons and is the primary water source for Hartford and surrounding towns, including my own West Hartford.

Jumping ahead a bit, I asked one of the MDC guys how water gets from here to there, knowing Talcott/Avon Mountain stands in the way. Pipes. Lots of pipes. But yes, the MDC Reservoir #6 is filled by Barkhamsted Reservoir water.

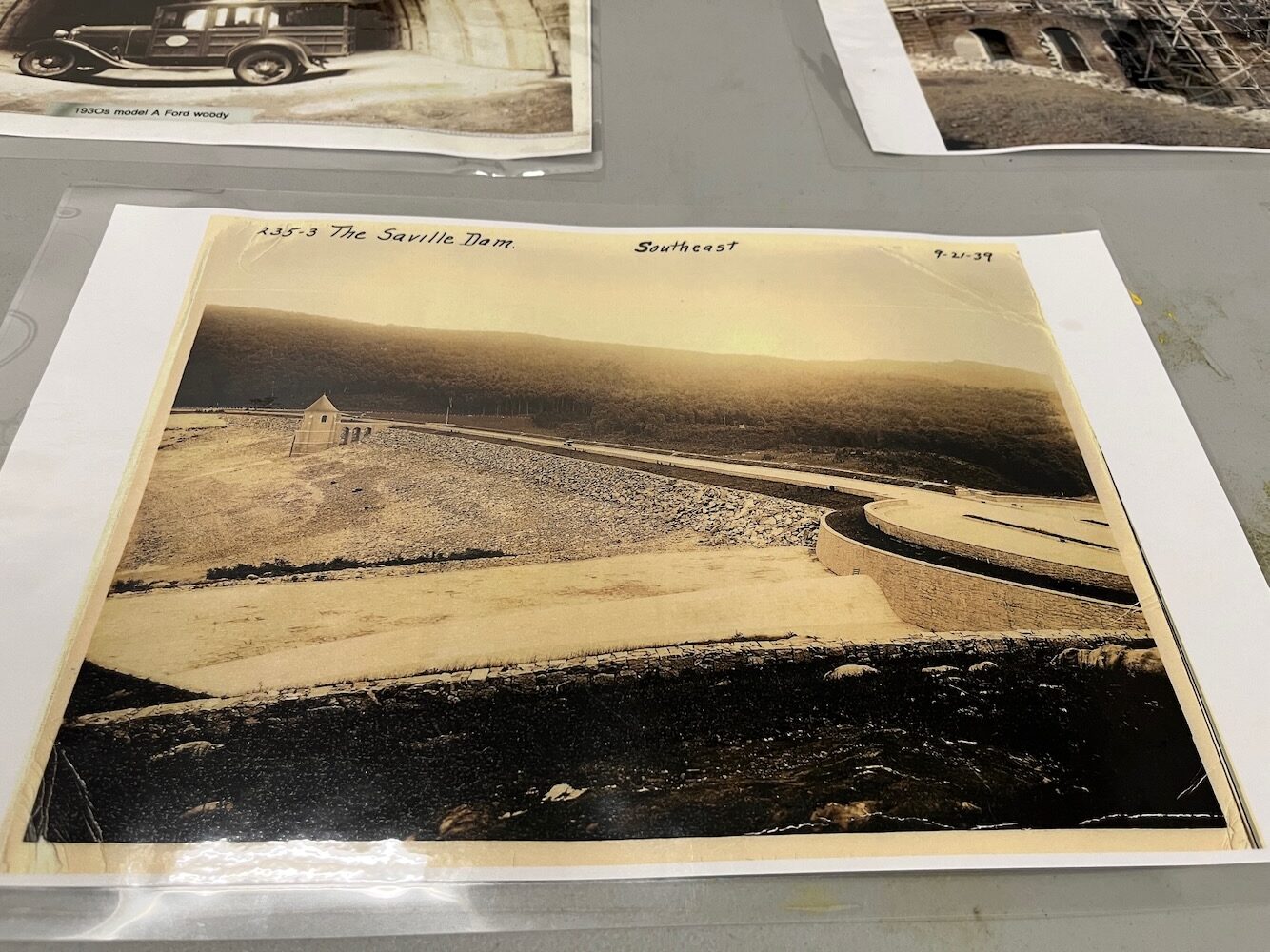

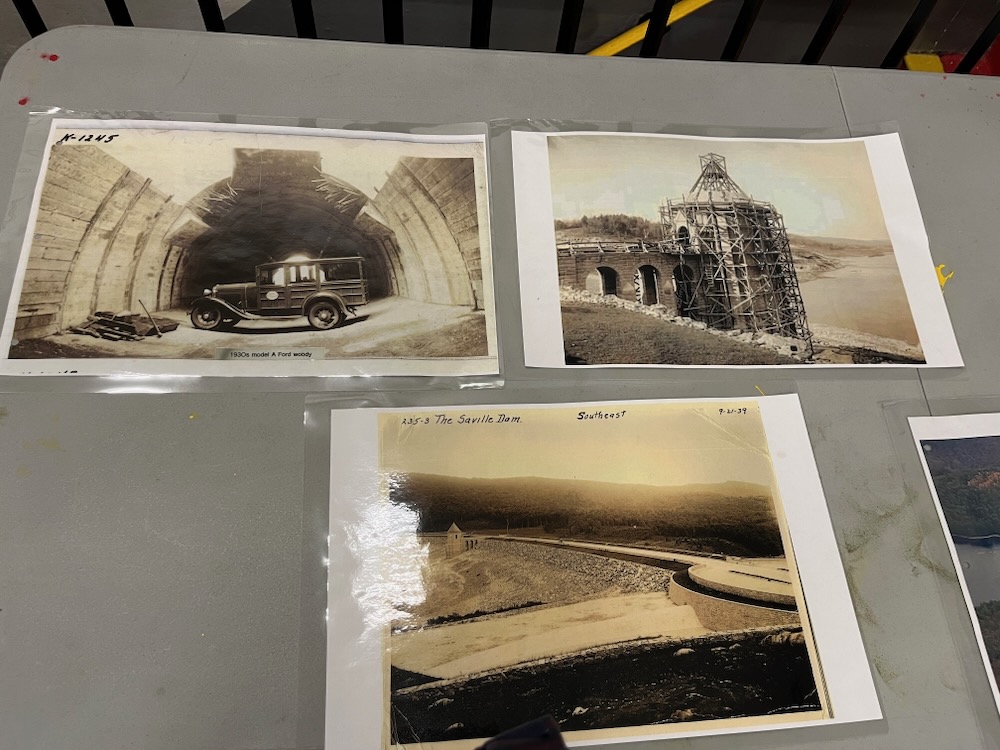

In 1927, the Metropolitan District Commission began to purchase land in the present-day footprint of the dam and reservoir. Construction of the dam commenced in 1936 while land to the north was being stripped of lumber and buildings. The scope of this project was massive. There are plenty of places to learn how they built dams a hundred years ago, so I won’t belabor the point. But a diversion tunnel was built, the compensative reservoir was created, and then the massive dam was constructed. It took four years and the dam was completed in May 1940, at a total cost for dam and reservoir of $10M (over quarter billion dollars today).

Although the Saville Dam was completed in 1940, it was not until 1948 that the Barkhamsted Reservoir finally filled to capacity. The reservoir flooded many buildings and farms of Barkhamsted, including the entire village of Barkhamsted Hollow. The village of Barkhamsted Center, partially flooded, lies just to the west of the reservoir. Its remaining buildings are part of the Barkhamsted Center Historic District today. More on these areas in a bit.

Paul Hart explained all this to us and then handed us off to the MDC guys, who were both friendly and informative. I may have issues with the way the MDC is run and who ran it for decades, but I certainly appreciate the lands it makes available for recreation and these two guys were great. Also great is a book called Water for Hartford by Kevin Murphy.

Lots of Hart’s information came from it and lots of this page is from Murphy’s writings. We were told the iconic gatehouse atop the dam that everyone loves was modeled after a little church in Essex, England called Little Maplestead.

It was built in… 1335.

Little Maplestead Church

Wow.

Let’s go inside.

But let’s also appreciate the craftsmanship of these doors. The doors here are original to the 1940’s and they are incredible. Once inside the pump room, beauty gives way to functionality, but a lot of what’s here is still original.

And still working. And when it’s not working, the designers made some decisions that allows for easier fixes, like floors and ceilings that open up for access to the pumps’ machinery. As I’ve said, I’ve been told that I’m not to publish any pictures from inside the dam.

Several of my pictures were quite boring shots of pumps and motors. Very meticulously cared for pumps and motors, mind you, but pretty boring stuff. We were led down some stairs to a walkway above two massive pipes. We were now “inside” the dam, looking at the two pipes that carry water to Hartford and several other towns. These pipes are also original, which is amazing – especially considering they travel miles and miles. I think one may go to Nepaug Dam to keep it filled and the other over to the West Hartford reservoir I mentioned.

No water is filtered here in Barkhamsted; straight up Farmington River water hits the pipes, which are gravity-fed and draws from the middle of the water column where there’s no silt and fewer fish – not that fish make it into the pipes.

pumps and pipes and motors

Heading down to the pipes

inside the dam! I made it!

Apologies for the pictures above. Gotta protect the MDC secrets.

There were displays in the room in which we first gathered. Historic pictures of the dam’s construction, and another one explaining how the send in robots to check the pipes and another one that cleans them.

It was all really cool.

But Paul Hart was antsy. We were behind schedule due to it was all really cool. This tour group had questions! And the MDC guys had long answers! But we were only halfway done with our tour and had to get moving.

So we got moving.

I didn’t really know what the rest of my day with these folks entailed, as all I cared about was the dam. As it turned out, my ignorance was, well, ignorant, as we were headed to another off-limits area within MDC land…

Barkhamsted Center (and Hollow)

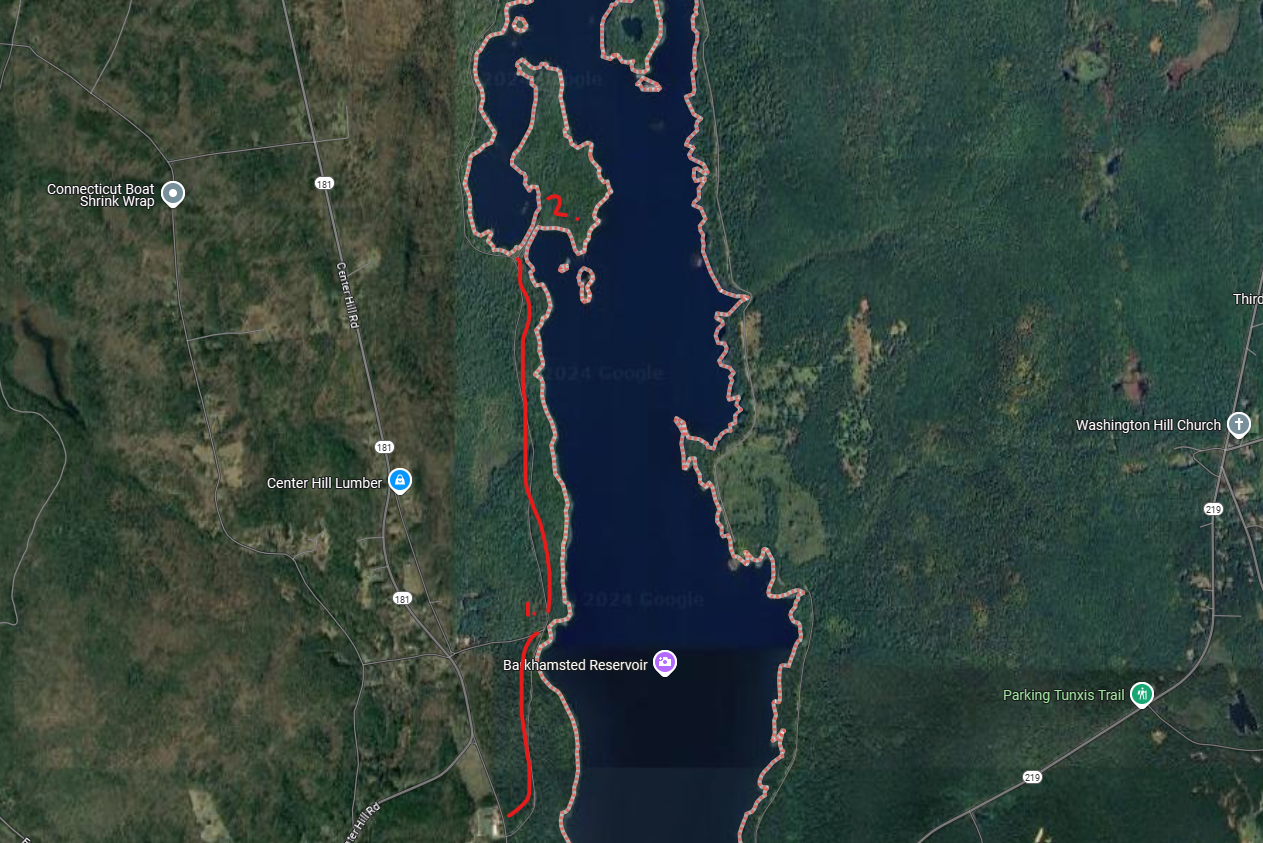

We reboarded the bus and drove north, along the west side of the reservoir. As we neared today’s Barkhansted Center, we veered right, through a locked MDC gate and into the woods across from the MDC regional headquarters building.

Whoa. I want to give huge thanks and props to our bus driver. She expertly drove a school bus up and down steep hills on a dirt road through the woods. I’m not sure she knew this was part of the deal, but she gritted her teeth and did a great job.

We stopped at a grassy opening in the woods and disembarked.

Now it was time for Paul Hart to really shine!

“Stop calling anything that exists in town today ‘the Hollow’. The Hollow is gone. It’s right there, behind me, underwater.”

And thus began the story of the town that was displaced by the reservoir.

As noted, in order to accommodate this massive body of water, the MDC cleared numerous acres of trees and farmland, redirected 20 miles of highway, and transplanted four cemeteries and the 1,300 graves within them. The greatest obstacle to the reservoir’s completion, however, proved to be convincing local residents to abandon their homes in the name of progress. For some reason, the people up in Hartland Hollow were quicker to sell than those in Barkhamsted Hollow. I assume there were just more to convince here, with some people holding out well into the Great Depression.

Once the Depression was full-on, the final holdouts sold in 1936. Then a land-stripping company from Ridgefield began removing the remaining obstacles to the reservoir’s completion. Local residents in need of work often found themselves employed in tearing up trees and fields in their old neighborhoods which must have been pretty weird. After a bonfire of building materials, trees, branches, and farming equipment turned piles of debris to ash, all that remained of the old residences were empty cellar holes.

Stops 1 & 2 on our tour. This land is off-limits and MDC doesn’t mess around

Paul was speaking to us under a huge oak tree in this grass clearing. We were standing it what was Barkhamsted Center before the dam. He pointed out where the schoolhouse was and some other municipal buildings. He pointed to the hill behind us and showed where the road traced up the hill; a hill known for its sledding back in the day. And regarding that schoolhouse and that hill, if you were to walk up that hill you’d come to a schoolhouse museum, owned by the Historical Society. That school house, The Center School House, was called the Center School House because it was here, um, in the Center.

But that pin oak tree was, to me, the most interesting thing of all.

This is Barkhamsted’s Constitution Oak. Your town may still have theirs growing somewhere prominent, like the town green or in front of your town hall. But Barkhamsted’s is here, in the middle of the woods, a couple miles from the nearest building. (The Constitution Oak was named to commemorate the constitutional convention held in Hartford in 1902. At this time, each town had 2 representatives in the General Assembly. The purpose of this convention was to change Connecticut’s constitution to provide proportional representation for each of it’s towns. A town with a larger population would have more representatives. The proposal was voted down. To remember this constitutional convention, pin oak seedlings were given to each of the delegates from the 168 towns in Connecticut. There are probably like 70 or so still growing. Quick, which is the missing town from our total of 169?

West Haven. C’mon people. It didn’t become a town until 1921.

Anyway, yeah, this WAS the center of town in 1902! And the oak here is the only remaining proof of that. I love this fact so much.

We then walked a bit into the woods along what was the road in the Hollow. Paul pointed out where one of the cemeteries existed back then. And a church, and more houses. Even though we were dry here, the MDC decided to move everything at a certain flood stage height of land.

We got back on the bus and plunged deeper and deeper in the forest. After reaching another small clearing, we disembarked, walked out to a spit of land, and allowed Paul to takeover our side conversations again. He told us about the farmers and their farms that were here. We could see foundations in the drought-affected water. We heard about the difficulties for so many to just leave their homes and community behind.

All the while, I was gazing out at pure southern New England beauty. Barkhamsted is beautiful, and I imagine with a patchwork of farms with a river running through, it was even moreso before the dam. This was a great day out and I want to thank the Barkhamsted Historical Society, Reenie Watson, Paul Hart, and the MDC for inviting me along. As effusive as I’ve been on this page, I haven’t captured how unique and interesting this tour was. I can’t recommend it enough.

I’ll append this with an article about the dam and the flooding of Barkhamsted Hollow, by Kevin Murphy, the author of Water for Hartford: The Story of the Hartford Water Works and the Metropolitan District Commission. This excerpt was published in Connecticut History, which until that link dies, includes some great historic photographs as well.

Barkhamsted Historical Society

![]()

There were two separate hamlets in the East Branch valley: Barkhamsted Hollow on the south end of the valley and the smaller Hartland Hollow in the north. Residents built small bridges to ford the river, which flooded its banks in the spring and kept both people and farm wagons close to home. The children loved the flooding: until the water receded, schooling would be limited. For farmers, though, the annual spring flood simply marked the beginning of another growing season. In addition to keeping dairy cows, sheep, pigs, and chickens, residents also raised tobacco, silage corn, potatoes, hay, and a large market basket of vegetables for their personal use.

The towns’ annual report show that teachers were paid $100 a month while selectmen made $25 for the year. Farmers took care of the roads in their off hours, billing the town at a rate of $4 a day. Firewood for the schoolhouses was purchased for $8 a cord, and gasoline was 17¢ a gallon. Barkhamsted Hollow had a new schoolhouse built in 1926: the land cost $500, the school building $3,245, and the outhouse $125. Each of the hollows had a total annual budget of about $18,000, more than half of which went to educating the young.

News from the outside world, following a path dictated by the terrain, flowed up the river from the town of New Hartford , through Barkhamsted Hollow, and, at length, up to Hartland Hollow. Babies in the two hollows were delivered at home, with a doctor visiting as soon thereafter as possible. The physician might travel from Winsted or New Hartford , the two slightly larger towns to the south. For many years, it was the unflappable Dr. Chester English who drove his horse and buggy from New Hartford to the farms in the valley.

The principal fixture of Barkhamsted Hollow was LeGeyt ‘s, the only general store in the valley. It was located at the intersection of East Road — which ran along the river-and Washington Hill Road, the unofficial line between the north and south sections of the hollow. The store was a tiny but surprisingly complete operation, selling household goods, meat, produce, and hardware. It also had a fairly large feed and grain department and housed the local post office.

When they started out in 1918, the LeGeyts had to live over the store, but a few years later an unusual opportunity arose. Thanks to Prohibition, Merrill Tavern next door effectively went out of business. Charles and Mae LeGeyt turned the old building into a home. Beginning in 1927, 14-year-old, pig-tailed Laura LeGeyt began helping her parents at the store, delivering sacks of grain and groceries up and down the valley. As long as there were men to offload the heavy hemp bags at their final destinations, she could muscle the family’s aged Reo Speed-Wagon along the dirt roads. Usually with 15 to 20 sacks per trip, the battered truck put in a long day with the unlicensed Laura at the wheel.

In Hartland Hollow , there were about 25 farms and private homes. Some sat on parcels of land as small as a few acres, while others rivaled Augustus Feley ‘s 345-acre spread. Like Barkhamsted Hollow, Hartland Hollow was divided between the north hollow-upstream of Route 20-and the south hollow downstream. Route 20 descended the mountain from the west more gently than it did in the east, the beat-up, narrow macadam road making an almost straight shot directly into the valley. Conversely, Walnut Hill Road -on the east-was a ledge cut, which snaked back and forth across the mountain between trees and boulders until it finally straightened for a quick run through a 30-foot-long covered bridge over the river. In the springtime, the beautiful rose-colored flowers of the trailing arbutus bushes completely blanketed the mountains on both sides of the valley.

By today’s standards, life in the hollows was harsh. There was no indoor plumbing or heating except what could be furnished by wood-burning, cast-iron box stoves. To keep warm at night, children wrapped a towel around a flat iron or a heated brick and took it to bed. On Saturday nights, hot water for baths was taken from a side tank on the wood stove and poured into a galvanized tub. There was no electricity-therefore no radios, telephones, or electric lights. Most people used kerosene lamps.

Little did residents know that their simple, bucolic life would soon come to an end.

The Beginning of the End

The MDC began acquiring landholdings in the East Branch valley in 1927, three years before the state legislature gave the agency permission to impound the waters of the Farmington River . The first farm acquired, late in 1927, was the Stewart farm in Hartland Hollow. The Stewarts, together with their son, daughter, and six grandchildren, were allowed to remain on the property for another six years while they looked for a new place to live. A month later, Mrs. Joanne Carrier sold her farm to the MDC and moved with her two daughters to Riverton , in the valley of the West Branch. Late the following year, the MDC bought two more farms: the 220-acre Waldo Miller farm and the 256-acre Wilber Miller property.

Two-and-a-half years after the first purchase, and just before the General Assembly granted the MDC its charter, the agency bought J. Alfred Cables ‘s 200-acre spread. The Cyrus Miller Tavern -and its 20 acres-followed. Things moved quickly for the MDC now, as they picked up Anna Schramm’s 80 acres in April 1930 and the Fred Stevens farm (95 acres) two months later. Just before Christmas, the MDC bought the 43-acre farm where young Pauline Emerick had watched her house burn to the ground just six years before.

While the MDC purchased the farms of Hartland Hollow in the late 1920s, the agency also was negotiating in Barkhamsted Hollow , but only a few Barkhamsted farms changed hands at that time. It was during the 1930s-the Depression years-that the bulk of these sales transpired, with a total of 80 properties coming into the hands of the water company.

In June 1931, the MDC bought 208 acres from Leon Dickinson in Hartland Hollow and, a month later, the Clifford Cables farm (140 acres). Soon thereafter, the MDC closed on still another large piece of property-Byron Stratton’s place-gaining 344 acres in one fell swoop .

Some sales affected folks more than others. It was an enormous blow when the 160-acre Talcott Banning farm was sold. On the surface, it might have looked like the loss of just another homestead, along with the usual livestock-until one considered the owner’s little sideline: Banning ran an illegal distillery. During those thirsty Prohibition years, he produced enough hard cider and apple brandy for everyone in the hollows. It was ironic that the whole valley had to suddenly go “dry” to slake a different kind of thirst in strangers 25 miles away.

Just before Thanksgiving 1931, it was Augustus C. Feley’s turn to sell his land. He did so in a big way, because he owned two farms. He sold his own place (345 acres) and the smaller Robert Stewart, Sr. farm. Feley was a practical man. Sensing the futility of a long, exhausting battle-with a preordained outcome-he simply accepted the MDC’s offer and moved on.

Early in 1932, the Metropolitan District let the contract for the clearing of the site where the new Saville Dam would be located and, in January, held a most unusual meeting at The Hartford Club. The desperation of the times was evident as MDC Chairman Charles Goodwin announced that, owing to the horrendous condition of the bond markets in New York , he would have to call a halt to the land purchases in the East Branch valley. However, exactly two weeks after the water board voted for a moratorium, they received an offer of sale from the heirs of the Ford Brothers farm, and they were back in the land-buying business.

Not all land transfers went smoothly. At a meeting in late 1932, the board faced an ugly task: condemnation. Two property owners in Barkhamsted Hollow had decided not to sell. The first, Charles LeGeyt, was the secretary and treasurer of Barkhamsted and by all accounts a good-natured and reasonable man. He and his wife, Mae, had acquired about 120 acres, their home, and the store, and they were determined to stay put. Even though the LeGeyts knew that any victory would be Pyrrhic, they held out for almost two years.

While her parents tussled with the MDC, 17-year-old Laura LeGeyt left the Hollow to attend nursing school in Hartford . All of her life, she would be haunted by her three favorite memories of the hollows: her father making ice cream on Sunday afternoons, the oyster suppers at neighbors’ houses, and the gorgeous, blue forget-me-nots that grew on the sides of the valley’s narrow dirt roads.

Unfortunately for the LeGeyts, so many folks had sold out that business had slowed to an occasional order from their neighbor, Harold Birden , the other holdout. Still, true to the spirit of the protest, LeGeyt ‘s Store remained open until November 1934, when Charles and Mae finally sold. Harold Birden , was made of marginally stronger stuff and lasted until April of 1936. He was the last to leave Barkhamsted Hollow .

Meanwhile, in Hartland Hollow, the Old Newgate Coon Club turned out to be the last private building to be surrendered. The 100 members of the club were mostly from Granby, with a smattering of men from the hollows. A local man, William Emerick, was a member and had a coonhound, Lady, who treed 32 raccoons in a single season, a record in the mid-1920s. After considerable negotiations, the Old Newgate Coon Club, together with its 89 acres, was sold to the MDC for $24,000.

After everyone was out of the valley, in the early summer of 1936, S. J. Groves , a stripping company from Ridgefield , New Jersey , descended into the hollows. The contract called for scorched earth in the 1,100-acre basin where the reservoir would sit. The work began in November and was completed the following August. Times were tough, and local people were not too proud to work for Groves , sometimes stripping land formerly owned by their own kin, neighbors, and friends. Using two-man whipsaws, the 75 workers felled towering hardwoods from morning to night. Trees, brush, house parts, barn wood, and old farm implements were stacked in an enormous pile in the center of A.C. Feley’s former tobacco fields. A local man, Paul Crunden, estimated the pile to be 60 feet tall and said that, when it was set ablaze, the flames “licked the clouds.” By the time Groves was done, there was nothing left in the valley but empty cellar holes.

The Last Dance

The MDC had told the residents of Hartland Hollow that their town hall would be the last building demolished, and the agency kept its word. The former residents wanted to have their 1940 Halloween dance in the old building. Former neighbors came from far and wide in their old Fords, Chevrolets, Plymouths, and rusty farm pick-ups. After selling their land, most folks had bought new farms and started over. They’d moved to Granby, Suffield, Winsted, New Hartford, Riverton, Pine Meadow, and Canton — wherever property was for sale.

The dance was a family affair, with a couple of generations of each family represented. Everyone had a good time square dancing, and judges awarded prizes for the best costumes-a box of cigars for the men and a bottle of perfume for the women. The revelry lasted until midnight without a single mention of the MDC or the loss of farms in the valley. What was done was done-simple as that.

A short time later-and just ahead of the rising waters-the MDC gave the order, and the 80-year-old town hall was burned to the ground. Eventually Hartland Hollow slipped beneath the waters of the Barkhamsted Reservoir, but the whole nine-mile-long catchment took eight years to fill. Water finally crested the spillway at the Saville Dam for the first time in 1948.

While the MDC’s new reservoir was essential to the denizens of Connecticut ‘s capital region, it created great hardships for the people in its path. The Barkhamsted Reservoir displaced upwards of 1,000 people. Nor were the families of the East Branch valley the only people uprooted by reservoir projects: Over time, thousands more were displaced by similar work in New York, Boston, and dozens of other cities in the U.S. But that was of little moment to the people of the East Branch valley. During America ‘s Depression years, they felt as helpless and alone as treed racoons.

Kevin Murphy is the author of Water for Hartford: The Story of the Hartford Water Works and the Metropolitan District Commission, from which this story was excerpted. Paul Hart told our tour group that this book was excellent and you should seek it out.

Perhaps I shall.

![]()

Barkhamsted Historical Society

CTMQ’s Houses, Ruins, Communities, & Urban Legends

CTMQ’s Forts, Canals, & Dams

Jamie Meyers says

Jamie Meyers says

November 27, 2024 at 10:30 amGreat stuff! Nepaug is one of my home birding patches and I go there literally a hundred times a year. Barkhamsted not nearly as often but I’m well aware of it. I never really have thought about the immense effort that was needed to build those places, the land and lives that were affected, and most of all, all those tunnels channeling water every which way. It’s pretty amazing. I’m particularly struck by how well the system works to this day, almost 100 years old later. What are we building in today’s society that will serve future generations this well?

I’ll have to look out for their next tour.

Marge Seiferheld says

Marge Seiferheld says

November 27, 2024 at 11:21 amSteve, both Burt and I were entranced with your coverage of the Seville Dam. We’re awaiting a return call from the historical society mentioned in your article. Thanks so much for highlighting this incredible piece of Ct history!!.

noreen watson says

noreen watson says

November 27, 2024 at 2:26 pmWOW What a through and interesting article. Thank you.I already got a call from someone wanting to know when the next tour will be!

Greg Amy says

Greg Amy says

December 4, 2024 at 1:18 pmCool tour!

Another ‘plus one’ for Murphy’s “Water for Hartford”. It’s on my shelf and gets pulled down for a re-read every once in a while…thanks for the reminder…

Jamie Meyers says

Jamie Meyers says

March 10, 2025 at 9:45 pmInspired by this piece, I went out and got a copy of Water for Hartford. Great read. I walk Nepaug with different eyes now. In my hiking and other activities I’ve come across several century old concrete markers with HWW stamped on them – Hartford Water Works. A couple can be found along the Tunxis Trail near the reservoirs.