Sing It!

Song, West Hartford

April 2021

I am wholly unqualified to write this page. I know, I know… I’ve said this many times before on this website, and especially when it comes to writing about restaurants, and especially about cuisines about which I know nothing. I am a white man. I grew up mostly in Delaware and Florida and live in Connecticut for goodness sake. Suburban West Hartford, Connecticut!

And yes, my wife is Vietnamese. I think I can speak to Vietnamese cuisine a little bit better than the next milquetoast white guy, but when it comes to the specifics of various Chinese cultures and cuisines, I’m pretty well lost.

Song (Photo from We-Ha.com)

But here we are. in the Sichuan region of China. Which I just now learned is in southwestern China. Chengdu is the city of note there, and giant pandas live there. Sichuan Province is also known for its long history of pungent and spicy food. And West Hartford is home three Sichuan restaurants owned by Chef Xingyu Huang and his wife, Sally Zhu. (They also own a fourth in Fairfield, and okay, Han Hot Pot House is technically in Hartford mere feet from the West Hartford line on Prospect Avenue.)

Chef Huang graduated from a top Chinese culinary school and was a renowned teacher specializing in contemporary Sichuan cuisine before becoming a very successful chef and restaurateur in China. At some point, Chef Huang moved to New York City, working in typical Chinese joints before coming up to Connecticut seeking Sichuan cuisine. He found almost none.

Spiced boiled egg

So he opened four of his own.

I’d been to Shu, over in Shield Street Plaza, but was most interested in Song in West Hartford Center. It is the presumably more authentic Sichuan restaurant while being fairly accessible, and that’s what I’m going for with this CTMQ Restaurant Tour of the World nonsense.

It bears mentioning that Chef Huang also produces a line of sauces called “Tasty Shu” which I can only hope was intentionally funny.

Jellyfish with vinegar

Actually, Song is similar to Shu, with the twist being Song’s menu allows for a wider variety of tasting, as they are served tapas style. Whichever one you go to, the key here is that the food is as authentic Sichuan, with all its spicy kick, as you’ll find around the state.

The restaurant itself is pretty cool. Minimalistic with gray tables, black ceiling, and dark wood walls. The food is the star of the show here, and the décor is telling you that. I, however, did not get to experience all of that for this meal, as I ate it in my own minimalist dining room.

Jellyfish

My wife was away with my younger son and I’d promised my older son takeout. I hadn’t told him it would be authentic Sichuan food, but I’m pretty sure that would have had no effect on Damian anyway. My hardest decision was to determine just how hard I wanted to go with the “authenticity” thing.

Song focuses on a “tapas” style of menu. There are lots of smaller dishes, divided into categories like Sichuan street food, noodles, dumplings, soups, sweets, and rice dishes. Many of the dishes feature the classic Sichuan chili-pepper-infused oil that produces a lurid orange-red glow.

Scallion pancakes and Chengdu wontons

And some dishes include Sichuan peppercorns, which contain a chemical that creates a slight tingly numbness in your mouth — which is signature Sichuan: hot and spicy, but magically not. If that makes sense. Lots of Song’s dishes look like they’re from the fiery pits of hell, but you can probably handle them.

From what I gather, other common Sichuan ingredients include bamboo shoots, green onions, pork, and peanuts. Of course, I am no Sichuan expert, so you probably shouldn’t take my word for it. Especially since… um… I wasn’t the biggest fan of much of the food I’d ordered. I can’t sing Song’s praises. With Hoang away, Damian and I plunged into a few pork dishes that we simply don’t ever eat.

But even some that we do, like the scallion pancakes, were heavier and greasier than I’d expected. But let’s roll through some of the “Sichuan tapas” we had.

Steamed pork dumplings

I had to get the Multi-spiced Boiled Egg; basically a hard-boiled egg but instead of water, it’s boiled in spices, soy sauce, and probably black tea. I’ll say there’s also some cinnamon sticks, Sichuan peppercorns, star anise, and bay leaves. My issue with it is that there was too much… something. Soy sauce? Maybe? I don’t know. I’ve had tea eggs at my in-laws several times, and this one just didn’t hit right for me.

Since I was going all-in, I had the Jellyfish with vinegar. Not something that many Americans enjoy. It has a challenging texture, both gelatinous and a bit crunchy – with a vinegar taste. I remember the first time I had jellyfish at a “traditional Chinese” meal with my wife’s family and I couldn’t wrap my head around the fact that humans eat jellyfish. Like, there just didn’t seem to be anything to them to eat, and certainly no nutritional value.

I still hold that opinion.

Onto the pork portion of the meal. Steamed pork dumplings were okay. Pockets of dough, with spicy liquid and pork inside. I think after not eating pork for 20 years, most pork menu items aren’t so delicious to me anymore. These dumplings did nothing for me.

But the Chengdu Wontons were excellent. They come with a spicy sauce. I’ll say it’s the classic chili oil, sesame oil, garlic, black vinegar, soy sauce, and sugar preparation. Spicy, tangy, and a little sweet. I think they were just more pork dumplings, but the soft, pillowy wontons were perfect.

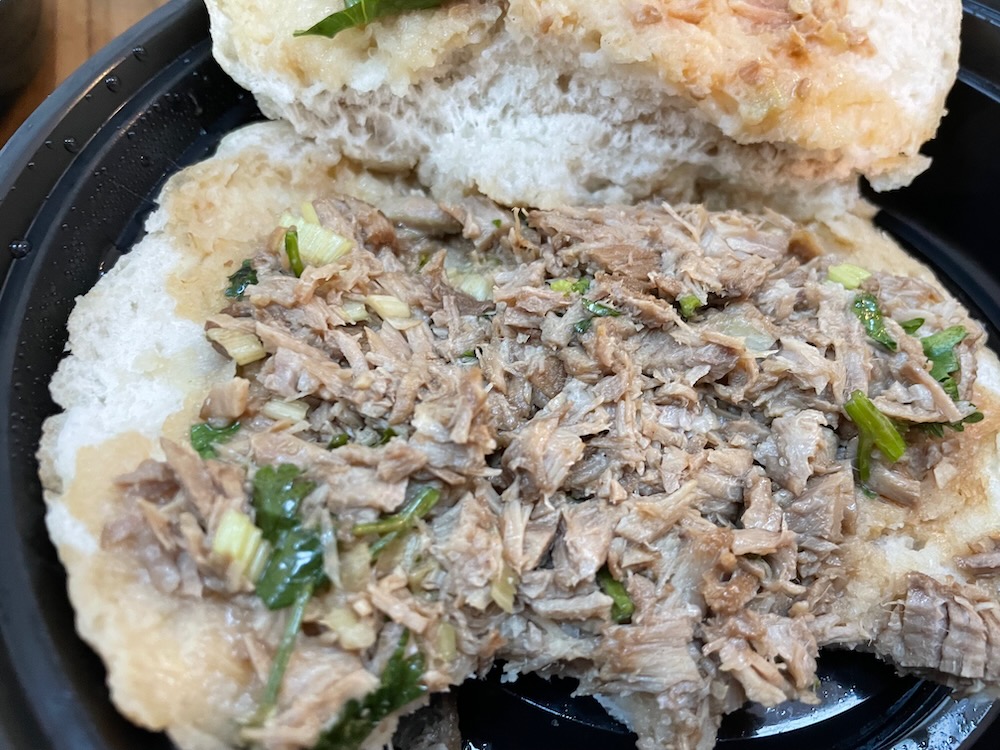

Pork Rou Jia Mo

Not perfect? (Well, it may very well be perfect, but I rather hated it and I see that it has been removed from the menu as I write this…) The pork rou jia mo. The direct translation for Rou Jia Mo is “meat in a bun,” which sort of makes it similar to what we’d think of as a hamburger, or maybe a Chinese sloppy joe. There’s the meat, and there’s the bun.

Supposedly, this thing dates back over two thousand years. There’s a school of thought that the sandwich – or “burger” – was invented in Xi’An in the Sichuan Province of China. (Granted, it was “invented” independently elsewhere as well.) Rou Jia Mo is a staple of Sichuan street food.

It’s basically pork, usually pork belly, cooked in a bunch of spices on a Chinese bun. Chinese Muslims – those that haven’t been put in interment camps anyway – use beef, other areas use lamb. And then there are the donkey fans. That’s right, Chinese donkey burgers. I’m not sure donkey is legal to eat in the US. I assume since horse isn’t, neither is donkey.

Nah

Anyway, the pork tasted like old leather and I didn’t get through more than three bites. The bun was dense and heavy. At least I had smartly ordered some familiar lo mein to fill up on. Song’s lo mein was perhaps the best lo mein I’ve ever had. Not greasy, flavorful, and just fresher than the usual Chinese take-out.

Song, named for the Chinese Dynasty and not the English word, is immensely popular and I’m sure the experience in the restaurant is better than what I experienced at home out of necessity. There are other adventurous menu items – lots of dishes with intestines and lots of noodle dishes that most Americans go for. I believe the critics, including the New York Times, that rave about Song and Chef Huang.

In fact, he’s so well respected that an Asian TV station made the short documentary above about his Sichuan cooking and it’s beautifully done. All of the chefs employed at Song are from different areas of the Sichuan province, as its important to the owners that they all understand the authentic flavors.

I strongly encourage you to dine at Song, if only to make me look dumb and culinarily myopic. Especially if you like pork and pork intestines and spicy noodles. I’m sure there are other Sichuan restaurants in Connecticut, but I believe the critics who say this is the best and one of the most authentic.

![]()

Song Restaurants

CTMQ’s CT World Food Tour

Peter says

Peter says

June 2, 2022 at 2:30 pmHorsement wasn’t made illegal in the US until 2007.