Ivory and Lace, In Their Rightful Place

Deep River (Google Maps location)

November 2015

As we Americans progress through the 21st century, some quarters are becoming “awoken” to things in their lives that have never been just or fair. We hear about “cancel culture” and all sorts of fake outrages fomented at the lower levels of online forums and blasted through the major cable networks and politician soundbites. Most of it is nonsense. (The “cancel culture” outrage is nonsense I mean, not bringing attention to hundreds of years of racism or sexism and the like.)

Charter Oak book

One of the quieter bundle of issues that we’re now “awoken” to is that of ivory, the 19th century ivory trade, and ivory in art and history museums. This brings us to Deep River and Ivoryton, Connecticut. (Ivoryton is a village in Essex right next to Deep River.) The next sentence is going to blow your mind:

At one time, manufacturing facilities in the lower Connecticut River Valley processed up to 90 percent of the ivory imported into the United States. And it all happened in Deep River and Ivoryton. That’s crazy. It all started with combs (hey, did you know the first comb factory in the US was in Essex?) and then progressed to piano keys and all sorts of vanity items and art.

A couple different ivory firms in the area merged following the Civil War and things really took off. They were bolstered by a cash infusion from a former ivory trader from Zanzibar (I just wanted to write that) and the industry exploded. By 1900 the two big factories employed more than 1,400 men and women. As smaller ivory firms opened around them, the company swallowed them up.

During the initial decade of the 20th century, the annual figure for number of pianos sold exceeded 350,000. The local Pratt, Read & Company, along with Comstock, Cheney & Company, supplied the majority of keyboards and actions to the various piano manufacturers, including Baldwin, Chickering, Wurlitzer, Everett, and Sohmer.

The factories also produced toiletries, toothpicks, billiard balls, letter openers, and many other household items made from ivory. These items emerged from the thousands of tons of ivory purchased and shipped from Africa. Comstock, Cheney & Company records show that the firm milled an estimated 100,000 tusks before 1929. That’s a lot of dead elephants. Everyone knows about the dead elephants.

Less well known is that slave labor moved the tusks the long distances from the African interior to the coast on the Indian Ocean. Thousands of tribal people found themselves forced into slavery to carry the tusks, often for hundreds of miles. One estimate claims that five enslaved Africans died for every tusk carried to a port. (That sounds bonkers, but it’s safe to say a lot of humans died for ivory in addition to the elephants.)

Which brings us to the Deep River Historical Society museum – who is not responsible for the deaths of any elephants or slaves. Ivory is a massive part of the town’s history, and of course that needs to be told through artifacts and exhibits. Ivory in museum collections has been a contentious topic during recent years, with some calling for its destruction. That seems… pretty dumb to me. It’s like the boycotters who buy a product just to burn said product. So dumb.

Museums with ivory art should accompany their displays with descriptions about the destruction of elephants and an acknowledgement of the human toll as well. Humans continue to exploit and destroy and corrupt and abuse. Shining bright lights on these actions is the only way to make more people “woke” to them. One person at a time I guess.

Aaah!

AAAHH!

Sorry Deep River, I know your museum complex isn’t all about the ivory! But as the entity with the only remaining ivory piano key bleach house in existence, this is the page I dump all of the above on readers. The design of the bleach house is unique; its prism-like shape optimizing the sun’s power in order to get a uniform white color on the ivory. These bleach houses used to be all over Deep River back in the day. Local workers kept logs to predict when these keys would be ready to ship based on the meteorological forecasts day by day.

This one just sort of… survived. It was used a greenhouse by a local farmer for a while and then given to the historical society.

The main museum is in the Stone House. The Stone House was built of local granite in 1840 by Deacon Ezra Southworth as a home for his bride, Eunice Post. The house includes both furnished rooms and dedicated exhibit spaces which have been carefully refurbished and maintained by DRHS volunteers through the years. Some furnishings and many of the artifacts on display are from the Southworth family. It’s very well put-together and presented.

In fact, I’ll dare say that in the category of “Small Town Historic House Museums in Towns Many Residents Don’t Know Are Towns,” Deep River’s is in the top three in the state. There are rooms exhibited with Southworth items from the 1800’s as all historic house museums must. But the collection here is deeper and more interesting than most.

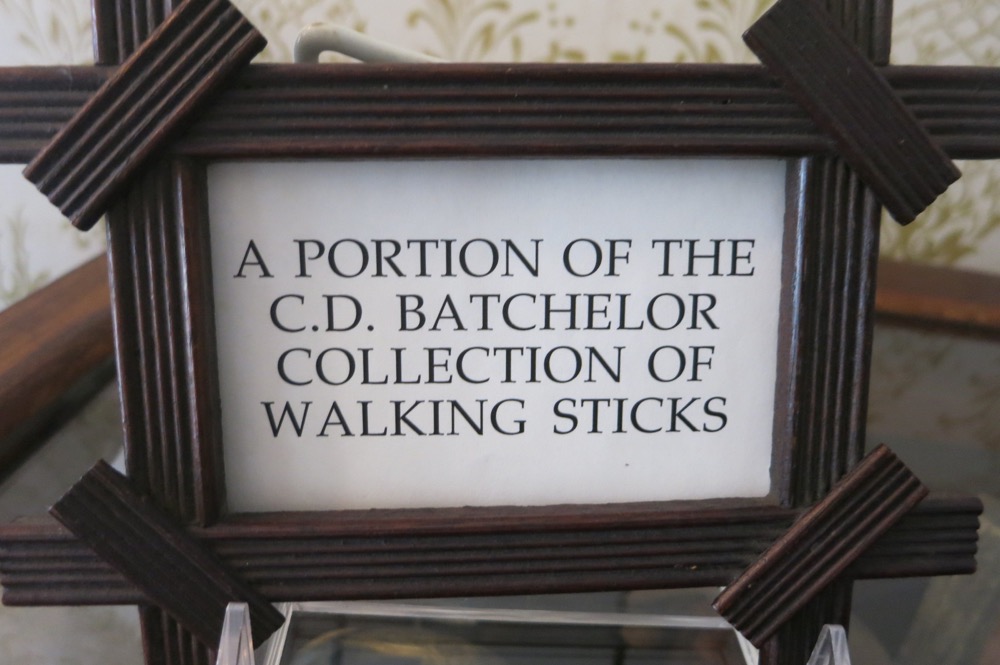

Local artist Obadiah Dickinson, the “first person from the Lower Connecticut River Valley to make a living as an artist” has some paintings displayed here. And there’s this bit of wonderful weirdness:

What’s that, you ask? Oh, I’ll tell you what that is:

Just a portion, mind you.

And then there’s an 1883 doll house from England which was so detailed and cool This is displayed in the bedroom exhibit which also has a crazy quilt, which I always like to mention simply for their name.

In the parlor along with the walking sticks, you will find a Victorian horsehair furniture and a piano made from the wood of the Charter Oak Tree and other vintage musical instruments including a melodeon and a cottage organ. The Marine Room tells the story of Deep River’s rich maritime history of ship building and the men of Deep River who sailed them around the world.

Oh yeah, my mention of walking sticks reminding me of sticks and, ha-ha, wouldn’t it just be the cutest thing if a little dollie had sharpened sticks, ha-ha, sorry, it’s so darling it just makes me smile – yes, a little dollie with sharpened sticks for arms? Can you imagine such a precious thing?

YOU DON’T HAVE TO IMAGINE ANYMORE, AHHHHHHHH!!!!

But back to the Munson Room which contains the permanent exhibits of the historical society. The ivory products are here, some cool WWII glider models that were built here, some Dennison wood planes made here – hey, are you a fan of wood planes? Did you know there’s a museum in Scotland (Connecticut) fully dedicated to nothing but? Sorry, where was I? Oh yeah, among the Deep River various and sundry are a bunch of examples of lace products.

Leavers Lace was a Deep River company that happened to be the last lace manufacturer in Connecticut. There’s a lot of lace here and it seemed to me that lace is as much a part of local business history as ivory. My only issue is that whoever thought hanging valuable historic lace towels on a towel rack next to the sink the bathroom urging visitors not to use the towel on the towel rack next to the sink… needs to have a talking to.

I felt tested.

There’s a refurbished carriage house here as well that can be rented out of for small events if you’d like. I certainly didn’t come here thinking the Deep River Historical Society’s Stone House would be any different than dozens of other similar historic house museums I’d been to. I was happy to be wrong and became a Deep River fan that day. The ivory trade history is ugly and brutal, but it’s also history. And learning about it here is worthwhile to everyone.

![]()

Deep River Historical Society

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Leave a Reply