The Lyman Homestead

Underground Railroad Trail, Middlefield

Pies. Berries. Apples. Cider. Golf.

Baked goods. Deli sandwiches. Vegetables. Corn Mazes.

Weddings. Pick Your Own. Christmas productions. Abolitionists.

Abolitionists? Abolitionists.

More than 150 years ago members of the Lyman family, whom we know now for their orchards and things listed above, earned a significant place in history by taking a stand against slavery. The Lyman family was involved in the Underground Railroad, openly voicing opposition to fugitive slave laws and refusing to turn runaway slaves in to authorities.

But since I won’t be writing about Lyman Orchards on any other CTMQ page, I think it bears mentioning that its history goes back way before the Underground Railroad was a thing.

The first Lyman in these parts was John Lyman who purchased 37 acres in what is now Middlefield in 1741. It has grown to over 1,100 acres and besides the orchards and farmland, it is a family destination. This place is fun! But we’re here for 10 generation of history. Members of the Lyman family are still involved in the business and the family and farm still feel like 19th century at times.

If you’re not popping in the store every time you’re anywhere near it, you’re doing something wrong.

And if you were a defender of slavery in the mid-19th century in the US, you were doing things wrong too. And you were about to lose a war, thank goodness. The Lyman family was not shy in their opposition to slavery at all. Beginning in the 1830s, William Lyman led the family’s abolitionist activities, including assisting fugitive slaves on their journey to freedom via the clandestine, illegal Underground Railroad.

Later, in 1850, William Lyman, his son David, his son-in-law James Dickinson, and three other men, arranged for a scathing rebuke of the Fugitive Slave Law to be published in the October 19th edition of the Sentinel and Witness newspaper, in which they wrote:

When an enactment, falsely calling itself law, is imposed on us, which disgraces our country, which invades our conscience, which dishonors our religion, which is an outrage upon our sense of justice, we take our stand against the imposition. The Fugitive Slave Law commands all good citizens to be slave catchers: good citizens cannot be slave-catchers, any more than light can be darkness. You tell us, the Union will be endangered if we oppose this law. We reply, that greater things than the Union will be endangered, if we submit to it: Conscience, Humanity, Self-Respect are greater than the Union, and these must be preserved at all hazards. This pretended law commands us to withhold food and raiment and shelter from the most needy – we cannot obey. . . . When our sense of decency is clean gone forever, we will turn slave catchers; till then, never. . . . Be the consequence what it may, come fines, come imprisonment, come what will, this thing you call law, we will not obey.”

This defiantly principled statement was a public declaration of the Lyman Family’s disdain for the institution of slavery and a tacit admission of their illegal involvement in the Underground Railroad. These men were willing to risk the loss of their property, livelihood, personal freedom and financial security to take a public stand on what they considered sacred religious and moral principles.

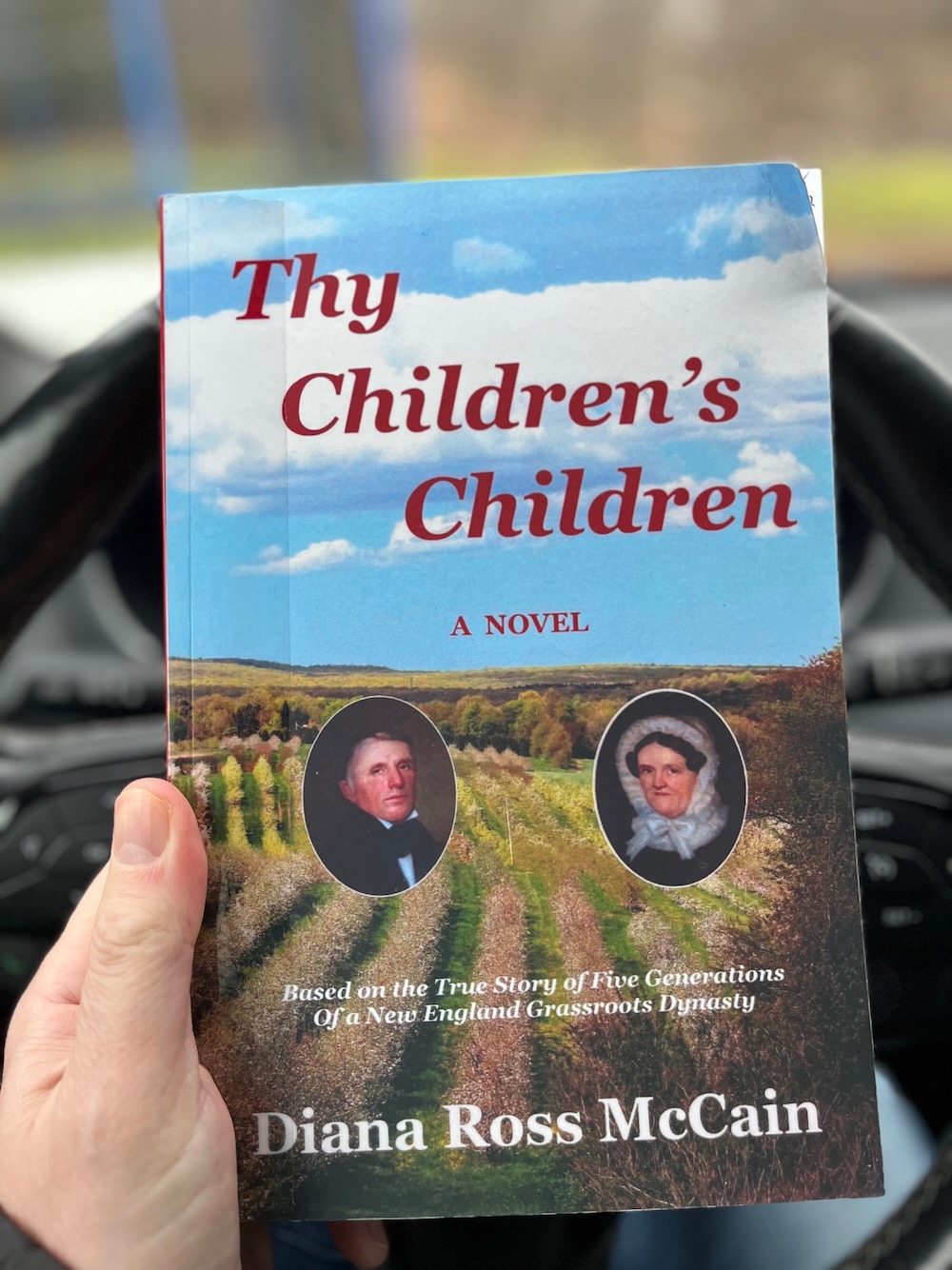

If you’re into this stuff, and really into the Lyman legacy, local historian Diana Ross McCain has written a 600+ page book of historical fiction for you. It’s called Thy Children’s Children and I imagine it will always be for sale at the Orchard store. It is “a fact-based fictional chronicle of the Lyman family from 1741, when they settled in Middlefield, until 1871, during which time they were involved not only in the abolition cause, but in the American Revolution, the temperance movement, and the advent of manufacturing and rail transportation in Connecticut.”

(I got it from the library and thumbed through it. This type of book is just not my cup of tea. But if you read it, do let me know how it is. Note: It is very, very long.)

Anyway, William Lyman was said to be a good dude. In a time when women were expected to simply get married and have a family, he showed his support of women’s education by sending his daughter to the Hartford Female Academy. He was a deacon at the church. A true pillar of the community. But sending your daughter to school from a farming community was a bit rogue at the time.

And so was being part of the Underground Railroad. Mind you, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was pretty draconian. Slave owners could come up north and get their slaves, and every citizen was obligated to help them with this task. Failure to do so resulted in a fine of $1,000 (in 1850, William Lyman’s entire farm was valued at $8,000) and six months in jail. Slaves could no longer stay in Connecticut, but had to flee to Canada, where they would be free.

And if you think the Connecticut liberals were all like Lyman, you’d be wrong. The state more or less supported the Act, if only for business reasons. So yeah, Lyman was pretty awesome, sending that letter to the newspaper with his son and the other men. That was not an easy thing to do.

The Gothic Revival house itself is beautifully preserved, just a stone’s throw from the store and the golf course. It was built in 1865 on the foundation of an earlier Lyman house. Today, it can be rented for weddings and other events.

So next time you’re apple picking or just apple purchasing, remember the legacy of William Lyman. Then eat some pie. Their pies are delicious.

Mmmm, pie

Lyman Orchards

CTMQ does the Underground Railroad Trail

CTMQ’s Freedom Trail page

Leave a Reply