First Impressions Are Everything

Wilton & Ridgefield (Google Maps location)

May 25, 2017

Weir Farm is a lot of things beyond being “just” a museum. It was Connecticut’s only National Park(ish) for years and years until Coltsville in Hartford got its NHP designation more recently – but that still has a long way to go until it’s open for visitors in any real sense. (In 2021 Weir Farm was redesignated from a National Historic Site to a National Historical Park.) In addition to hiking trails, Weir Farm is also on the Connecticut Art Trail, the Connecticut Historic Gardens Trail, and it’s listed among the 1,000 Places to See Before You Die in the USA.

All of that is great, except it means that it’s… big. And I struggle with writing about the big things in our little state. But I must and I shall.

Weir Farm was the summer home of pioneering American Impressionist Julian Alden Weir from 1882 to 1919. For Weir and his famous contemporaries — artists Childe Hassam, John Twachtman, and Albert Pinkham Ryder—the farm’s landscape offered the perfect setting to paint en plein air and experiment with light and color to create American masterpieces.

Weir Farm has been drawn and painted by artists ever since. Today, the 68-acre national park is one of nation’s finest remaining landscapes of American art. It is the only national park dedicated to American Impressionist painting. And it’s right here in Connecticut, straddling the border between Wilton and Ridgefield.

Hoang and I had a planned day off from work and made the trek southwest. We have a mutual friend who lives in Wilton, and when I was looking at the best way to get to Weir Farm, I noted that it was pretty close to our friend’s house. “Eh, it’s a random weekday and she’s busy and we’re on a pretty tight timeline,” I thought, and we happily drove through the rain to Wilton.

We parked and crossed the road as a car waited at the stop sign. The window rolled down. A woman’s voice called out.

“Hi guys! Oh my god! What are you doing here?!”

You know that emoji with the gritted teeth smile? Yeah, that was me. Hoang? She never knew how close Jen lived to this place and was genuinely surprised at the chance encounter. Sigh. I am not an awesome person.

That ridiculousness behind us, we ventured into the visitor’s center. I’d always known this was a National Historical Site/Park, managed and maintained by the National Park Service, but I guess I didn’t really expect the full-on NPS experience. Hosts dressed in those olive and tan outfits with the wide-brimmed hats and everything. The familiar NPS logo everywhere. This place is absolutely one of Connecticut’s richest treasures and relative few even know about it.

And while some friends have joked about it being The Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir’s farm, those jokesters might get a kick out of this quote from J. Alden Weir’s daughter, an accomplished artist in her own right: “Weir found the world beautiful and he spent his life showing others the visions he had seen.” That sounds positively trippy to me.

There are several buildings here, celebrating the life of Weir, his family, and all the impressionists and sculptors who spent time here in the late 19th century. We began in the Burlingham House Visitor Center. Oh, by the way, this whole joint is free! And I should also note that the houses and property were almost always owned by some Weir descendent or family friend (all artists) until they gave it to the public.

For example, The Burlingham House bears the name of Julian Alden Weir’s youngest daughter, Cora Weir Burlingham. Cora lived in this house from 1931 to 1986. Today the Burlingham House serves as the park’s visitor center and and museum store. Back in 2017, Hoang and I were given the run of the place to go on our own merry self-guided tour. I know that COVID changed up things here a bit, so your mileage may vary.

J. Alden first started acquiring land in 1882 and continued adding acres until 1907. He bought the bulk of the land for $560. Actually, what he really did was trade a still life painting he’d bought for $550 to an art dealer for the farm. The dealer, Erwin Davis, demanded ten dollars on top of the painting. In lower Fairfield County – obviously before lower Fairfield County became home to some of the wealthiest people in the world.

Weir’s painting career seemed predestined – but not as an impressionist. Born into a family of artists, he studied art at New York’s National Academy of Design and later matriculated to Les Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. While in France he was close to the plein air genre painter Jules Bastien-Lepage. Weir’s initial response to the emergent impressionism was one of disbelief. “I never in my life saw more horrible things. They do not observe drawing nor form but give you an impression of what they call nature. It was worse than the Chamber of Horrors,” he wrote.

Obviously, his opinions changed after moving here to Connecticut. While living at the farm, Weir shifted his artistic style from portrait and still life work to focus on the inspirational nature of the landscape here. After he made that shift in style, critical acclaim followed. Weir vaulted to the forefront of the American art establishment which is what attracted others to come hang out with him and paint in a mini art colony.

The Visitor’s Center hosts changing exhibits and serves as a nice introduction to the full property. Beautiful gardens have been recreated behind the house, including a colonial revival Sunken Garden, terraced lawns which were once the site of numerous vegetable gardens, and the Weir Garden, which was created in 1915 and features a fountain, sundial and a rustic cedar fence. As I mentioned, this is one of Connecticut’s official Historic Gardens.

To the south are fields that border the Weir Preserve. In 1969, Cora donated 37 acres of her land to the Connecticut Chapter of The Nature Conservancy, marking the start of the Weir Preserve. Today the Weir Preserve includes 110 acres of diverse woodland and wetland habitat owned by the Weir Farm Art Alliance, a park partner.

Hoang and I mosied around the property and went to the other buildings.

Here, amidst rocky fields and woodlands, Weir spent nearly four decades painting. His artist friends Childe Hassam, John Twachtman, Emil Carlsen, and Albert Pinkham Ryder often joined him. Together, they created masterpieces of light and color on canvas that came to define American Impressionism. After his death, Weir’s daughter Dorothy Weir Young, an artist in her own right, and her husband, sculptor Mahonri Young, carried on the artistic legacy at Weir Farm. They were followed by New England painters Sperry and Doris Andrews.

I just remembered that President Obama had a Childe Hassam painting hanging in the Oval Office. Just throwing that out there.

Although Weir gravitated towards painting outside, he needed a place to paint inside as well. Built shortly after Weir purchased the farm in 1882, he used the Weir Studio to create many of his masterpieces. Today, the studio is historically furnished, and visitors can view original and reproduction sculptures, paintings, etchings, artists tools, furnishings, and collections. And that’s exactly what we did.

Originally, the Weir Studio had brown walls and a light blue green ceiling. However, Weir realized how surface colors can impact the colors on his canvas. To fix this, he painted the whole studio gray. Stars that were placed on the studio’s ceiling by Weir, which… I’d like to do that at my house.

After Weir’s death, the studio was primarily used for storage. The Weir Studio has been restored to circa-1915 and is historically furnished. Weir’s paintbrushes, pallets, pigments, and paint boxes have been preserved and are on view inside the studio.

When we visited, we were allowed to walk around the studio and see these things up close. I’m not sure that’s still allowed. The lessened accessibility might be (have been) a COVID thing? Or maybe it has to do with the change from a National Historic Site to Park? I don’t know.

But the fact that this whole place is pretty much as J. Alden Weir lived and worked is pretty darn immersive and impressive. His tools, furniture, and paintings (of course) is a singular place among the hundreds of National Park properties around the country.

Despite the fairly heavy rain, we walked around some of the grounds. I specifically wanted to see the “portable studio” Weir used to get around the property to paint different scenes “inside a studio.” Weir would occasionally paint from his “Palace Car,” a studio built with assistance of his resident farmer, Paul Remy. (Note to self: Get a resident farmer.) Set on runners and pulled by oxen, the car had windows on four sides and an oil stove, making it a portable, all-season studio. It eventually became a playhouse for his children.

I wonder if this was a commonplace thing for the Impressionists? Regardless, it’s pretty cool.

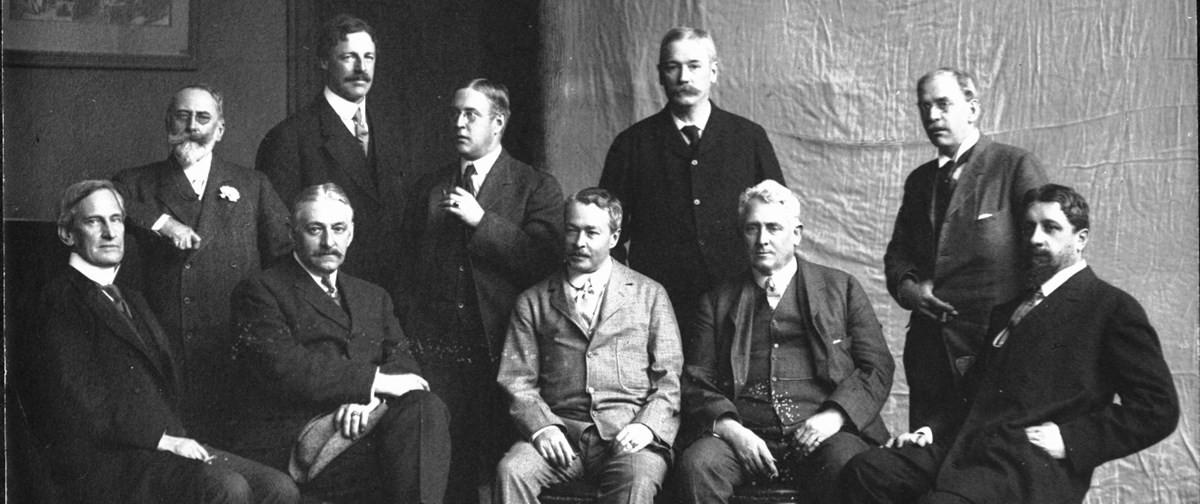

The Ten American Painters (1908): (back row l to r): William Merritt Chase, Frank W. Benson, Edmund Tarbell, Thomas W. Dewing, Joseph DeCamp, (front row l to r): Edward Simmons, Willard Metcalf, Childe Hassam, Julian Alden Weir, Robert Reid.

NPS Photo

J. Alden Weir was one of America’s most important painters. Always a talented portrait artist, Weir’s reputation as a landscape painter and leader of the American Impressionists grew through the 1890s. At the Farm, Weir joined his friends Childe Hassam, John Twachtman, and seven other like-minded artists in forming a new artists’ group known as the “Ten American Painters,” or “The Ten.” This group provided an alternative to the staid exhibitions of the staid art trends and organizations of the day. The Ten overtook the art world and are considered among the most revered American artists to this day.

Weir Farm is a unique and special place in our little state. There aren’t many cool free things to do out in Ridgefield or Wilton, so you really should take advantage of it. And who knows, maybe you’ll trade a painting and get your own farm and become a massively influential artist as well.

Go for it.

![]()

Weir Farm National Historical Park

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

CTMQ’s National Historic Parks

CTMQ’s Connecticut Art Trail

CTMQ’s Connecticut Historic Gardens page

Leave a Reply