Wait Just a Cotton Pickin’ Minute…

Windham Textile and History Museum -The Mill Museum, Windham

January 2019

CT Museum #408

I do not know why this museum has two names. Or rather, one official name that is two different names. My 20 seconds of research into the important matter took me to the museum’s website and old blog posts from 2019. In April of that year, the museum was referred to as The Mill Museum. In May of that same year, it was called The Windham Textile and History Museum – a.k.a., the Mill Museum. For the rest of that year, the name sort of flip-flopped or was referred to in two parts.

At some point, a parenthetical was used and as I write this in 2024, it is as the page title says.

Seems rather clunky to me. (Says the guy who started ctmuseumquest dot com then changed it to CTMQ.org but never closed out the original URL with the host so it still lives, owned by some Chinese scammer. Good times.)

The Willimantic section of Windham is one of Connecticut’s many former industrial cities. Hulking mills still loom throughout the downtown area just as they do in New Britain, Manchester, Waterbury and many others. Willimantic was known as the Thread City, a theme that is still a source of local pride. And this rather large museum, located in the historic former headquarters of the American Thread Company, preserves and interprets the history of textiles, the textile industry, and textile communities in Connecticut.

Ambitious? Yes. Are they successful in their mission? Also, yes. This place is easily one of the best museums in the northeast part of the state.

The Museum’s historic main building was constructed in 1877 by the Willimantic Linen Company as a company store and library. The store was on the first two floors; the library and an adjacent meeting room were on the third. The American Thread Company, which purchased the Willimantic Linen Company in 1898, converted the first two floors — and, eventually, the third floor, as well — into its main office building. When it opened, it was intended to be a modern, impressive symbol of the Linen Company’s place as one of the country’s largest thread mills and the city’s largest employer.

I had young Calvin with me, so my visit couldn’t be all “boring” industrial history lessons. Though I will admit, without a docent experienced in entertaining second graders, Calvin did grow a little antsy from time to time – but the museum does a very good job of mixing in lots of hands-on activities and “fun” stuff throughout.

The museum was founded in 1989. At that time, the Museum acquired ownership of two buildings that had been part of a factory complex once owned by the American Thread Company which shut down operations here in 1985. A real estate developer bought the plant and donated the two buildings that would become the museum. He turned the larger mill buildings into lofts and offices and stuff.

For the Irish

The larger, infinitely more attractive of the two buildings is known as Dunham Hall. This was where the museum began and it occupies all three floors today. Built in 1877, it housed the company store for the Willimantic Linen Company and a library for the workers, their families, and other members of the community. Later, when American Thread owned the joint, Dunham Hall was converted to offices and reconstructed much of the structure.

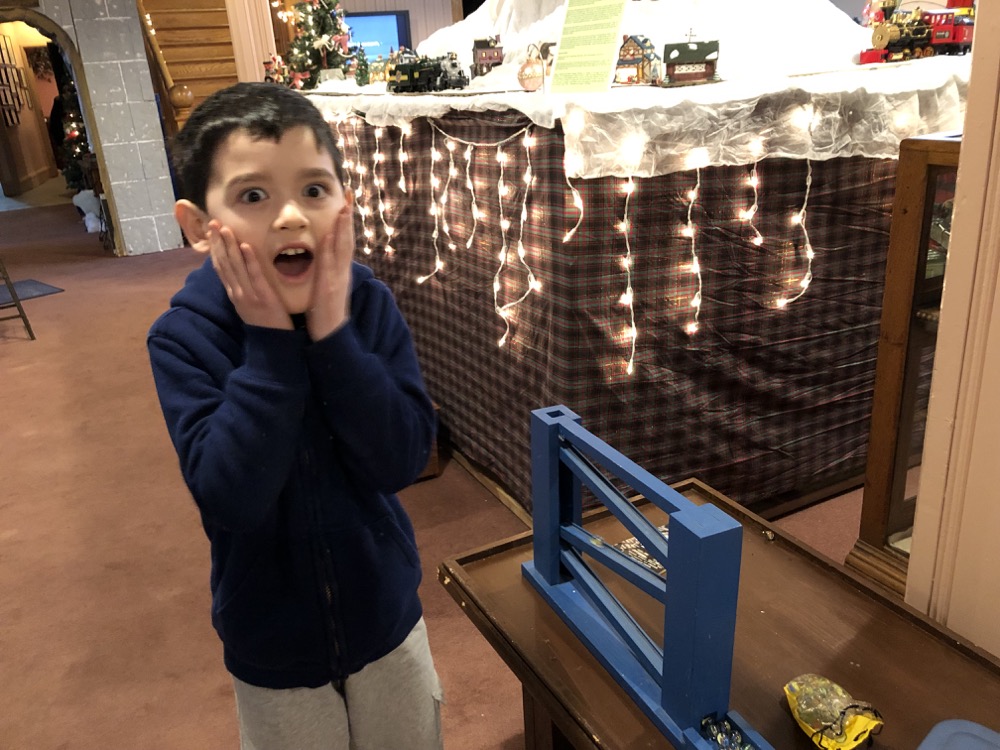

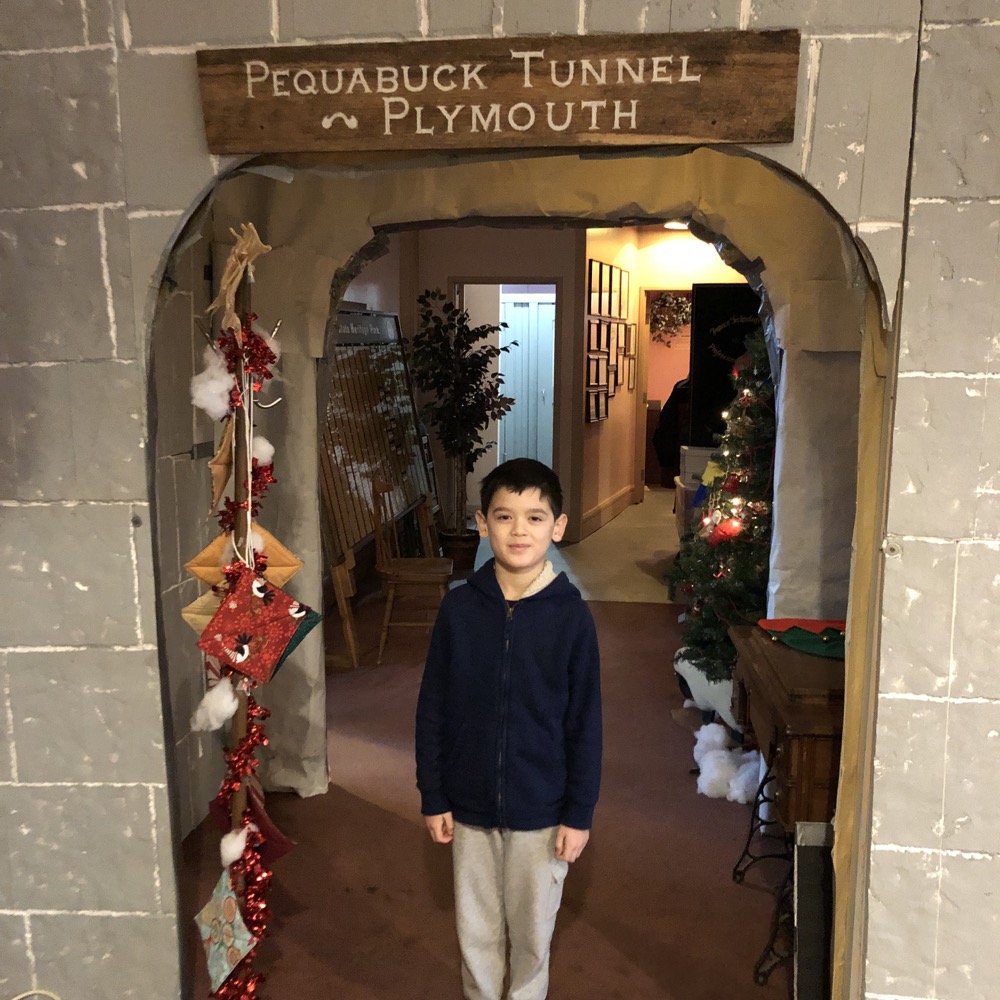

Alright, let’s get to the actual museum. Calvin quite enjoyed the model trail set up on the first floor and wouldn’t have budged if not for me cajoling him. I have no idea what there’s a Pequabuck Tunnel display here, as that’s many miles west out in Plymouth, but here you are:

We made our way all the way up to the third floor which was a library back in the active mill days and… is still partly a library for the museum today. Dubbed the Dunham Hall Library, it provided reading material for mill workers and some of the community at-large as well. There’s a small gallery up there as well, but I’m going to guess this third floor isn’t a big hit with most visitors.

We did see this scrap of cloth:

A sign claims this is a “scrap of cloth from the first web woven by water power.” Ever? Like, in the world? I have no idea. It’s from Slatersville, RI. I’ll let someone else research the veracity of that claim. Let’s go to the second floor.

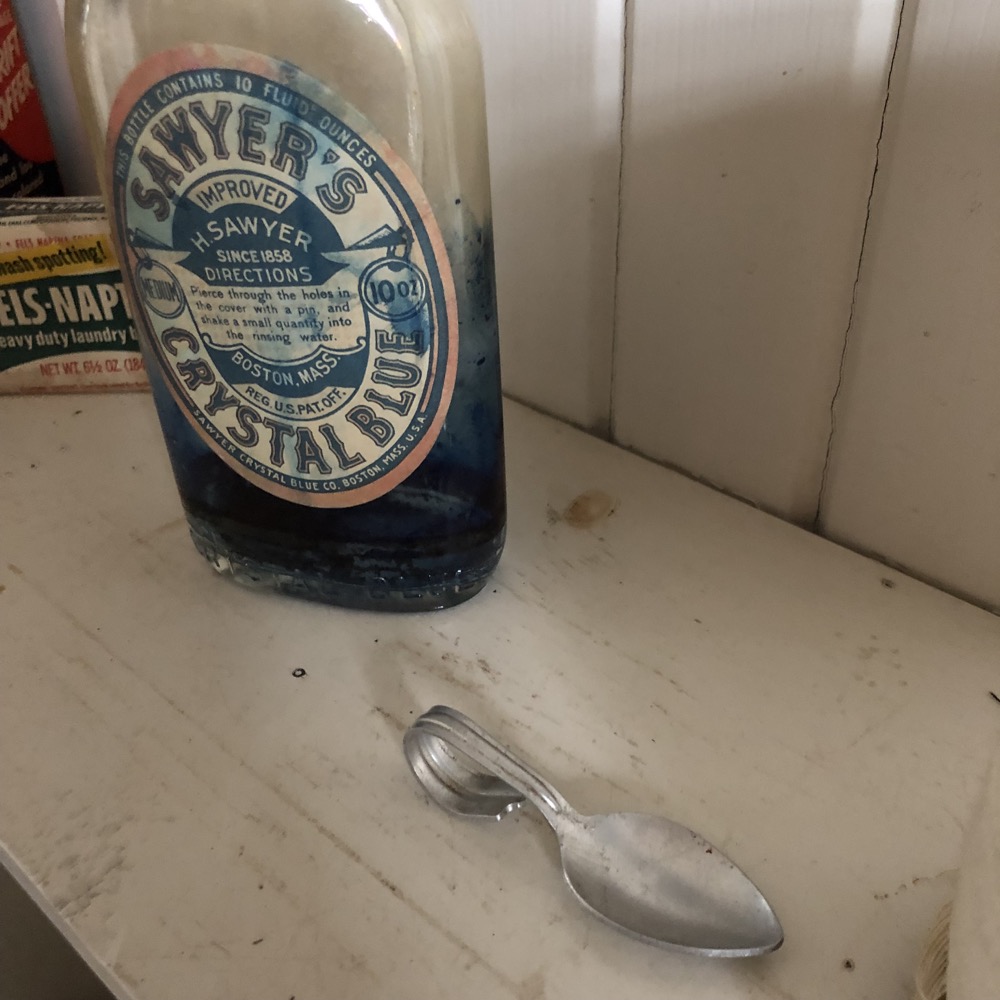

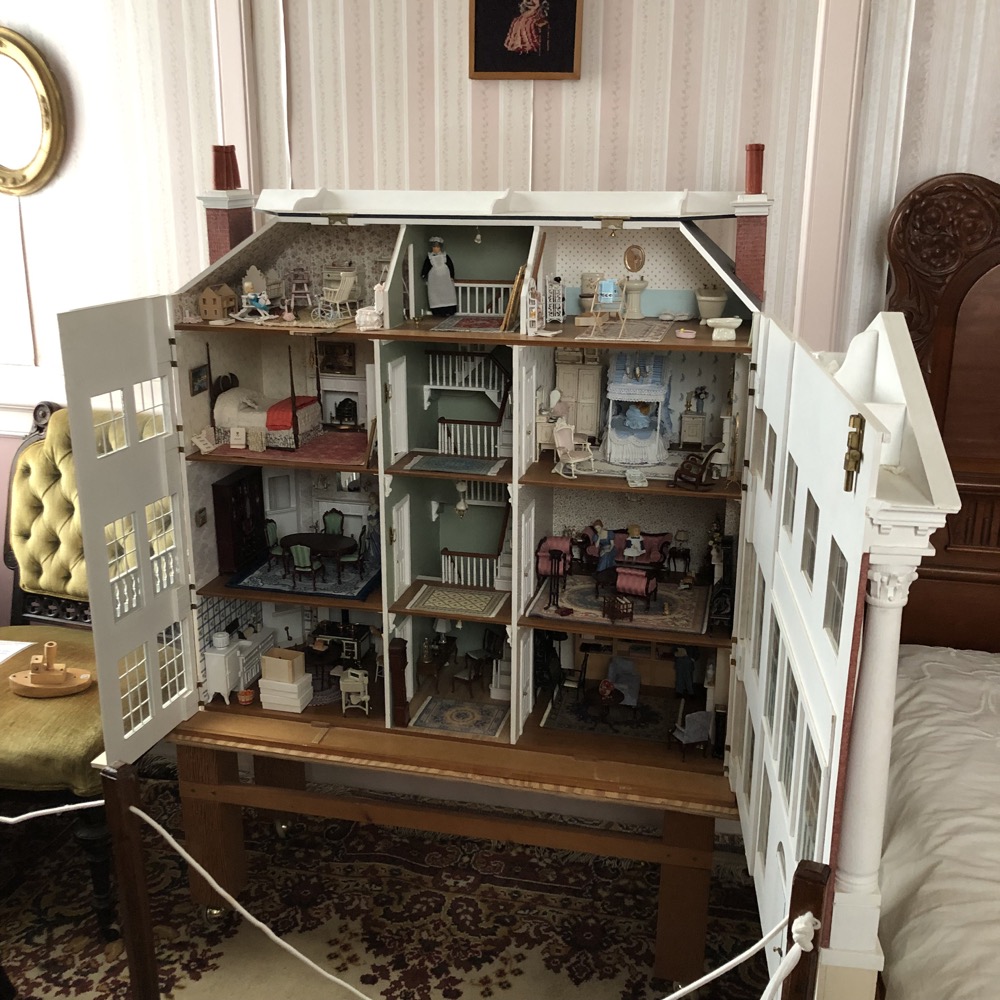

The museum dubs this floor “Thread Mill Square” and it portrays the daily lives of mill workers and their bosses. A typical worker’s bedroom and kitchen as well as the same for a manager. There’s a weaving studio and lots of exhibits about daily life at the mill.

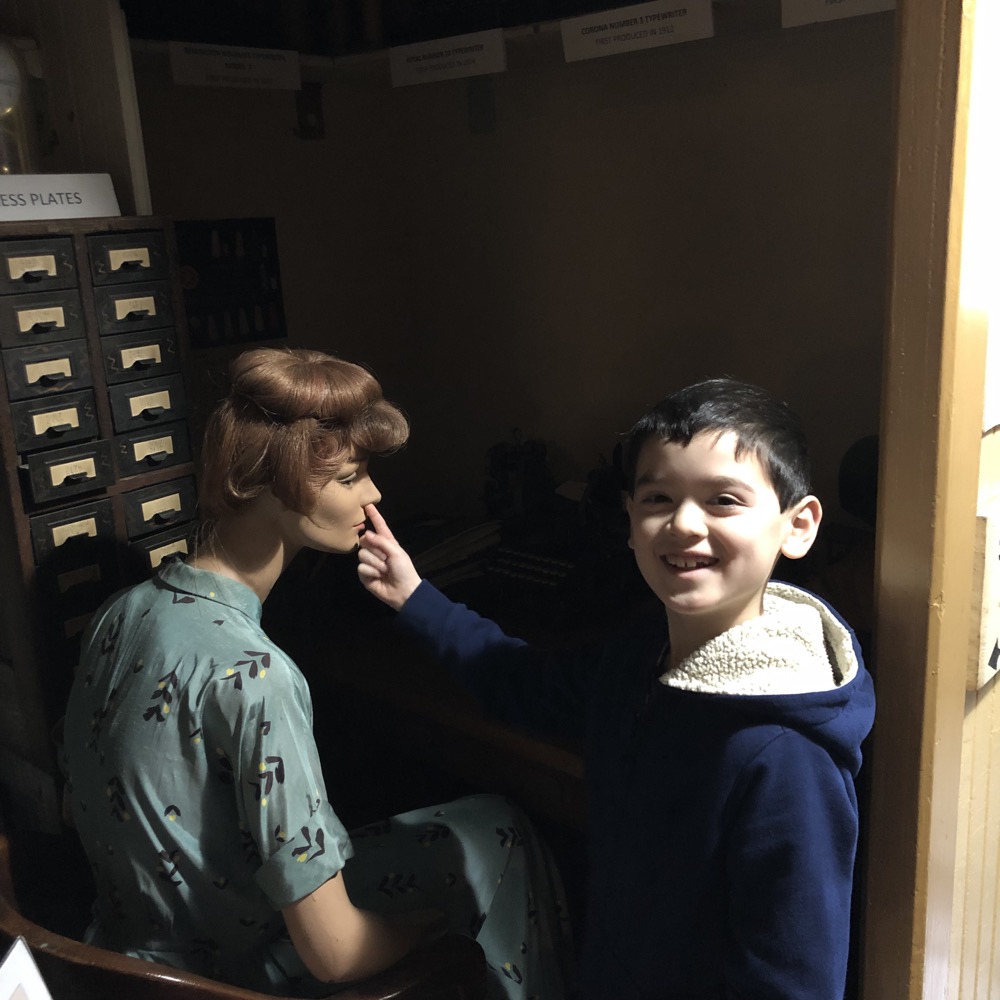

Turns out that you can pick your friends AND you can pick your friend’s nose

The idea here, I guess, is to show that workers were poorer than managers. Heck, drive around Willimantic and look at the famous Victorian houses there. Those are the mill managers’ homes from back in the day. Then go drive around the rest of Willimantic. Those would be the equivalents of the worker bees’ homes. Nothing has changed in the intervening century. You enter the manager’s “house” through an ornate veranda with copper gutters.

Company housing both attracted workers and gave owners the opportunity to recapture wages in the form of rents. Often ten or twelve people shared a unit, and the dining room and sometimes the parlor were also used as bedrooms, with the kitchen the only common room.

The Mill Company Office Exhibit features a desk and chair from the American Thread Company, a safe, a vintage typewriter that visitors can use, and numerous pieces of other vintage office equipment. The owners of the earliest factories did not expect they would need much office space, and so 19th-century mill offices and office buildings tended to be quite small.

Still, the level of detail on display here is impressive and it’s interesting to see how people lived in mill towns back in the day. These were the people that made the US what it is today; the laborers and toilers. Which led to unions and labor laws. Which led to outsourcing to countries without unions or labor laws. Which didn’t lead to the massive wealth gaps we have in the country today, and that’s a topic I certainly can’t speak intelligently on, so let’s move on.

Of course here, “moving on” simply means looking at more textile industry history. The museum displays are really, really well done and they do make it interesting. Far more interesting than I’m making it seem, I swear. And the museum is honest about working conditions, low salaries, and the entire cotton hypocritical cotton industry in the 1800’s. By the time of the Civil War in 1861, they had become the nuclei of a growing city of about 4,000 inhabitants — a home to mill workers, managers, and owners, and to merchants, engineers, shop clerks, lawyers, doctors, teamsters, carpenters, seamstresses, and others who, either directly or indirectly, depended on cotton for their livelihoods.

From the museum’s website:

It’s unavoidable: Cotton was farmed by slave labor in the southern states, shipped north to places like Willimantic, Connecticut and turned into clothing and other cotton goods. Then they were sold and worn by Americans of all stripes. The idea that everyone in Connecticut was anti-slavery is a bunch of nonsense.

Slavery, which many thought might gradually disappear, instead expanded as, in the largest forced migration in American history, tens of thousands of slaves were “sold south” from the tobacco-growing sates of Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky to the “cotton belt” of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, coastal Texas, and parts of Arkansas and Tennessee. By 1850 there were four million slaves in the South, as compared to only a half million free blacks in the entire United States.

cotton was “king” in New England as well as in the South. Beginning with Slater’s Mill (which at first produced woolens, but switched to cotton as raw cotton became more available), cotton mills by the scores sprang up along the rivers of Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, where the combination of abundant rainfall and hilly topography meant plenty of waterpower — and where shippers and merchants had sufficient surplus capital to invest in the risky new venture. By 1830, not only had raw cotton surpassed wheat as America’s most important agricultural export, but cotton products had become the country’s leading manufactured export, as well. If King Cotton led to more slavery in the South, in New England it led to the expansion of what nineteenth-century people called “free labor,” or wage work. In both regions, increasingly larger proportions of the population worked for someone else, as opposed to being self-sufficient farmers or craftspeople.

Not Surprisingly, the People of Willimantic Had Decidedly Mixed Feelings About Slavery and Abolition. On the one hand, almost nobody wanted to see slavery in Connecticut. As New Englanders, they were proud of their “free” (i.e., wage) labor system, which they regarded as more modern and economically advanced than slavery, indentured servitude, and other forms of bound labor. The city’s small African American minority, of course, opposed slavery in any form. But many whites, while opposing slavery in Connecticut, feared that challenging it in the South might create an irreparable breach between North and South, splinter the two national parties, the Democrats and Whigs, and perhaps result in secession or even civil war.

There were also economic reasons for people in Willimantic to tolerate slavery in the South.Southern slaves planted, tended, and harvested most of the cotton that Willimantic’s busy mills manufactured into thread and cloth. Many feared that abolishing slavery nationwide might drive up the price of cotton (by increasing the cost of labor) and thereby imperil their own jobs and profits. Moreover, the majority of the white residents of Willimantic would have shared the insidious racial prejudice against African Americans that was so prevalent at the time. As Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jennifer Frank of the Hartford Courant point out in their 2005 book, Complicity, Connecticutters were as complicit in American slavery as anyone else in the United States. A lot of them were willing to tolerate it, just so long as it remained in the South, safely out of sight.

I highly recommend learning more about this fascinating disconnect on the museum’s website, here.

And what was used to make those cotton garments? Sewing machines of course.

The Mill Museum has a collection of more than 75 antique sewing machines, many of which are on display. The exhibit also includes toy sewing machines, thimbles, and other sewing paraphernalia. There’s a whole wall of thimbles. But not buttons. You want buttons? Go to the Button Museum in Waterbury. (Yes, that’s a real thing.)

One particular manufacturer was Wheeler and Wilson. They were a 19th-century manufacturer, located in Bridgeport. Back then, Wheeler and Wilson was the United States’ second-largest sewing machine manufacturer, trailing only Singer. It was said that the Connecticut company’s technology was superior to Singer’s, so what happened? Singer bought out Wheeler and Wilson in the early 20th century.

Of course they did.

Calvin and I had our fill of such fun and crossed the small parking lot to the second building, known today as Jonathan Dugan Building. The Willimantic Linen Company and American Thread Company printed their own labels for shipping boxes, display packages, and thread spools. This “vertical integration” saved on expenses. An authentic era-accurate Print Shop Exhibit is set up in one corner of the Factory Floor Exhibit.

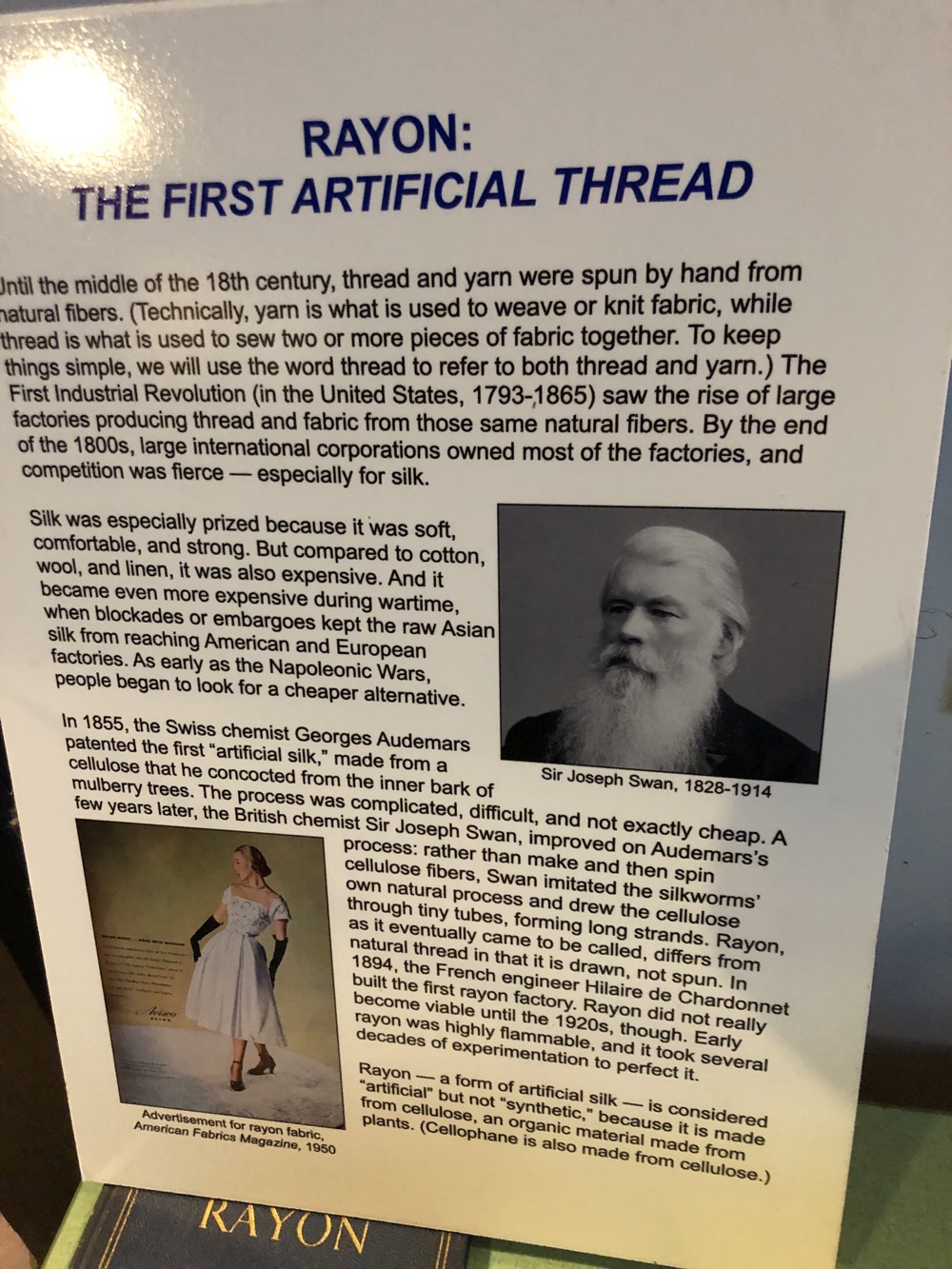

Calvin seemed to enjoy the Dugan Building more than the main building. Perhaps because he knew we were nearly through with the museum? Nah, every kid loves Jacquard looms and carding machines. I also learned something myself here:

Huh. That differentiation between synthetic and artificial is interesting to me.

Some more goofing around with cotton with Calvin and we called it a day here. As I said, the Mill Museum does a great job making this part of Connecticut’s industrial past interesting and yes, even fun for kids and adults alike.

Here are some more pictures from the Dugan Building:

![]()

Windham Textile and History Museum – The Mill Museum

CTMQ’s Museum Visits

Leave a Reply